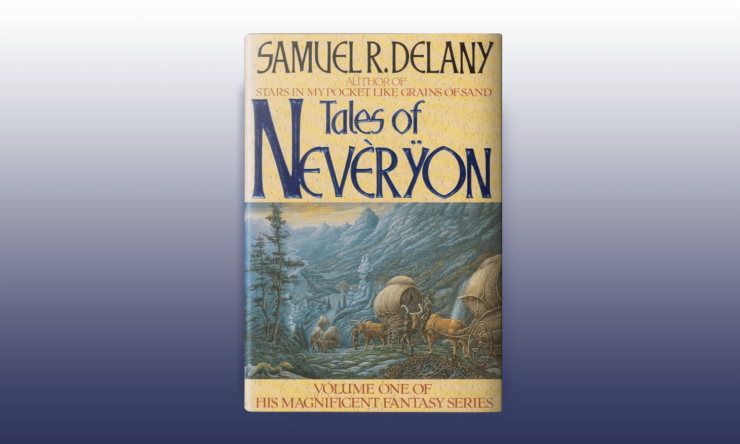

Tales of Nevèrÿon (1979) is a wonderful mosaic novel, Delany at his best.

It was published in 1979, but because of the vagaries of British publishing I didn’t see it until 1988, and I had to check the date twice because it feels to me to belong a decade later. It’s interesting to consider that this book was written (1979!) so early in the first boom of fantasy as a marketing genre—Judy-Lynn Del Rey, seeing the success of The Lord of the Rings had deliberately published Terry Brooks’ The Sword of Shannara in 1977 to capitalize on the idea of fantasy trilogies, and suddenly fantasy out of nowhere was a big thing.

Before 1977 it’s fair to say that fantasy was a genre written by oddballs (up to and including Tolkien) or for children, but then between 1977 and 1980 fantasy for adults became huge, bigger than science fiction, selling in huge numbers to an eager public. And this fantasy explosion took a little longer in Britain which is probably why this book didn’t make it to teenage me until a decade after its original US publication. Because Delany too was writing fantasy—but of course, his wasn’t like the fantasy everyone else was writing.

Tales of Nevèrÿon is definitely and explicitly fantasy, but it doesn’t have that most defining quality of the genre, metaphysics. There’s no magic, religion isn’t shown as having effects, there isn’t even any fate or providence. What we have is the feel of fantasy. The feel of fantasy, only two years into the birth of the genre as a genre? But it isn’t at all like Tolkien, or Brooks, Eddings, etc.; if it’s like anything it’s coming out of the family tree of Leiber, Vance, and the writers of the magazine Unknown. By the “feel” of fantasy maybe I mean that it’s medieval? But it’s not medieval Europe—not with these jungles and lizards and barbarians and slave collars. Is it Cimmerian? By which I mean it seems to me as if perhaps it’s coming out of the tradition of Howard’s Conan the Barbarian, with its distinction between civilized and barbaric, its easy rising, fast falling kingdoms, its mines and jewels and chases through marketplaces.

Delany says this book, that sword-and-sorcery fantasy generally, is about the change from a barter economy to a money one. That reads a little oddly now after reading David Graeber’s Debt (2011) which argues that there never really were barter economies. Be that as it may, Delany imagines one, in detail, and then plays seriously with the underlying economics, while tossing us bouncing balls and the rhymes children repeat while playing with them, barbarian princes, a child empress whose reign may be just and generous, or bloody and barbaric, depending on how you want to look at it, but must always have two adjectives, never more or less. We have a mosaic novel made of separate stories, called the Tale of X, the Tale of Y, and the tales reflect and refract like bright mirror shards. I’m always comparing Delany’s writing to jewels and prisms, and this is very definitely a bright sparkling mirror, like the mirrors the boys wear strapped to their bellies in the Ulvayn islands. But the protagonist of that story is a girl, and the story is about an old woman, but what it’s really about is how seeing something in a mirror reverses but seeing it in another mirror you can see the back of the paper, and whether and what that applies to. And the book is about these reversals, but what it’s really about is freedom and slavery.

In a very odd way re-reading it now reminds me of Patrick Rothfuss’s The Name of the Wind. No, it’s nothing like it, but it has the same trick of throwing you a layered net of references in one place and then giving you another angle on one of them in another place, and another in a third place, so that in the end you know more than you know, and certainly more than you’ve ever been told. This is the book that made me come up with the term “mosaic novel” (in 1988…) because it really does use the individual tales so cleverly to make a bigger picture. There’s a very specifically genre pleasure in being tossed world-pieces, some of them upside-down, and some of them glittering, and then assembling them for yourself into a whole world, or even the illusion of a world. The thing it has in common with Rothfuss is that you know all the pieces fit to make a whole worth having, nothing is accidental or an afterthought, and you know that even before you can see the big picture.

There’s a note in the odd section at the end of Triton that in science fiction everything must be mentioned at least twice, in at least two different contexts. I believe Delany does that there and also here. Everything is mentioned in two different contexts but a lot of it isn’t explained, and a lot of other things are explained, and then themselves met with in another context. This is a book where you have to think and pay attention, but it’s also a book where you have to relax and let it happen to you, and which you can only see in any kind of focus after it’s finished. And by “you” here, I mean me, of course.

It’s a very playful book, despite the heavy subject. It’s full of lush description, repeated references, and layered imaginations that fit smoothly together. He’ll mention the fisherwomen of the Ulvayn Islands as a passing detail, and then you’ll find yourself in the next story on those islands in the house of one of the fisherwomen, examining gender and change, while mending nets and inventing writing systems. One of the subthemes of the book is how dynamic technology is, how fast everything changes, which isn’t what we expect from fantasy, but why not? Why can’t someone remember fountains being invented and then being a fad, and someone else reflect on how the introduction of money has changed the meaning of marriage? Why is this something we think of as science-fictional? It’s interesting to see it in a lush fantasy context. It’s interesting to wonder why we imagine the technology of fantasy worlds as static—as we (wrongly) imagine the Middle Ages as unchanging. This is not a fixed world, this is a world in motion, as whirling and chaotic as one of those balls bouncing off the cisterns as the children chant rhymes and run to catch it.

There are several sequels, and the whole Nevèrÿon set makes up a self-reflecting mosaic as this first book does, but for me it’s less successfully seen as a whole thing. I’ve never really liked the novel Neveryóna that is book two—but maybe I’d be old enough for it now? Book three is incredibly powerful, but as this is about slavery that is about AIDS, and that one was written in the Eighties when the AIDS epidemic was both terrible and badly understood, and Delany takes that moment in The Tale of Plagues and Carnivals and makes something powerful and so painful that I really need to be in a good place to even contemplate reading it. I should read the whole thing again, I know I should, but not right now. So, have just this book, this single, perfect, weird, beautiful book. It’s worth it.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two collections of Tor.com pieces, three poetry collections, a short story collection and fifteen novels, including the Hugo- and Nebula-winning Among Others. Her novel Lent was published by Tor in May 2019, and her most recent novel, Or What You Will, was released in July 2020. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here irregularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal. She plans to live to be 99 and write a book every year.