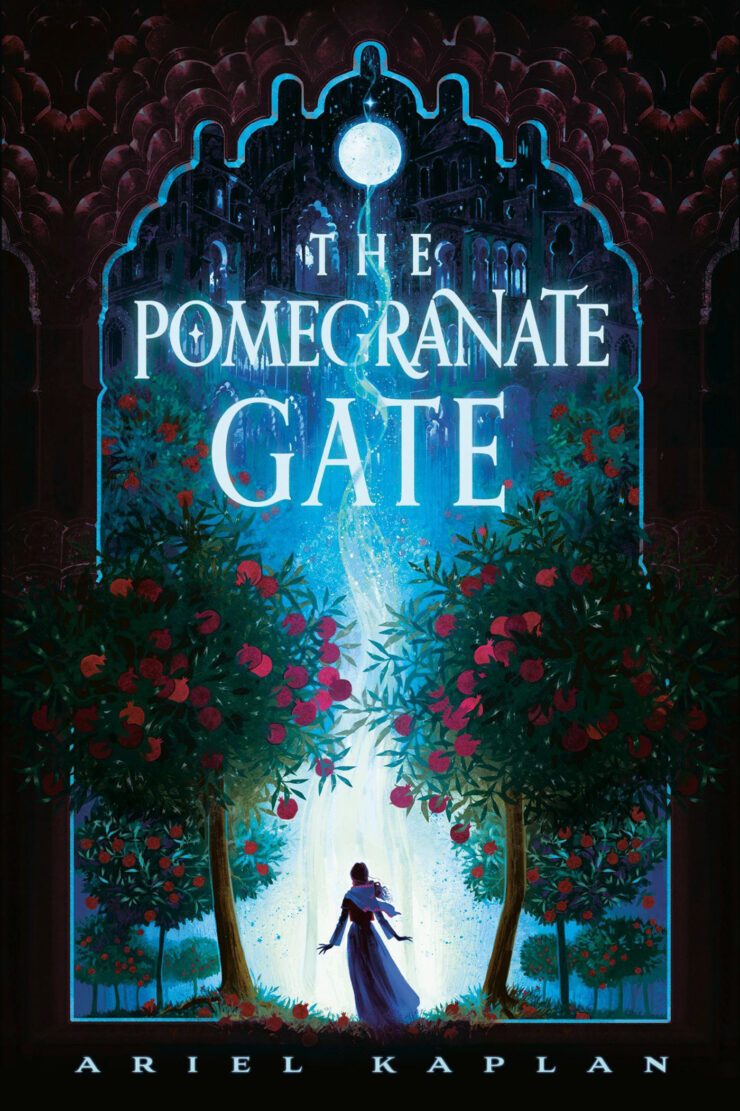

We’re thrilled to share the cover and preview an excerpt from Ariel Kaplan’s The Pomegranate Gate, the first book in a Spanish Inquisition-era fantasy trilogy inspired by Jewish folklore—available September 26, 2023 from Erewhon Books.

The first adventure in the Mirror Realm Cycle, a Spanish Inquisition-era fantasy trilogy inspired by Jewish folklore, with echoes of Naomi Novik and Katherine Arden.

Toba Peres can speak, but not shout; sleep, but not dream. She can write with both hands at once, in different languages, but she keeps her talents hidden at her grandparents’ behest.

Naftaly Cresques sees things that aren’t real, and dreams things that are. Always the family disappointment, Naftaly would still risk his life to honor his father’s last wishes.

After the Queen demands every Jew convert or face banishment, Toba and Naftaly are among thousands of Jews who flee their homes. Defying royal orders to abandon all possessions, Toba keeps an amulet she must never take off; Naftaly smuggles a centuries-old book he’s forbidden to read. But the Inquisition is hunting these particular treasures–and they’re not hunting alone.

Toba stumbles through a pomegranate grove into the mirror realm of the Mazik: mythical, terrible immortals with an Inquisition of their own, equally cruel and even more powerful. With the Mazik kingdoms in political turmoil, this Inquisition readies its bid to control both realms.

In each world, Toba and Naftaly must evade both Inquisitions long enough to unravel the connection between their family heirlooms and the realm of the Mazik. Their fates are tied to this strange place, and it’s up to them to save it.

Brimming with folkloric wonder, The Pomegranate Gate weaves history and magic into a spellbindingly intricate tale suffused with humor and heart.

Buy the Book

The Pomegranate Gate

From author Ariel Kaplan:

“I adore this cover—especially the backdrop of the Andalusian palace haunting Toba from beyond the gate, and those vibrant, verdant pomegranate trees. I think this image evokes the fairytale-feel of The Pomegranate Gate perfectly.”

Ariel Kaplan grew up outside Washington, D.C., and spent most of her childhood reading fairy tales and mythology before settling on a deep love for Jewish folklore. She began studying the history of medieval Spain and the Convivencia while working on a Monroe Scholar project at the College of William & Mary, where she graduated with a degree in History and Religious Studies. She is the author of several books for younger readers. The Pomegranate Gate is her first fantasy novel.

Chapter One

Naftaly was dreaming again, in that strange dream-landscape where the stars whirled overhead like snow on the wind and the people he met all had square-pupiled eyes.

They were all strangers to him, the square-eyed people he dreamed of—all save one: his father. In Naftaly’s dreams, his father’s eyes were odd, too, though waking they were wholly ordinary. Naftaly did not know if his own dreaming face had the square-pupiled eyes as well, having never come upon a mirror in his dreams, but he assumed so. He wondered how that looked, if it made him seem strange, or handsome, or hideous. No one ever remarked on it. His eyes, awake, were the same dark brown as his father’s, round-pupiled and not particularly interesting.

In this dream, he’d come across his father eating oranges while sitting on a bridge Naftaly did not recognize, spanning what he supposed was meant to be the Guadalraman. They sat on the wall together, watching a swath of people traveling from one side of the river to the other, across the bridge which was lit at intervals with lights that seemed to burn without flame. It was a busy night, Naftaly thought. Probably he was dreaming of the end of a market day, though the people had no goods. He thought his subconscious could have come up with more interesting details: bolts of cloth or jugs of oil, or perhaps some sweets.

Naftaly was a tailor, son of a tailor, son of the same, though the elder Cresqueses had been at least passably good at their trade. The latest son was somewhat lacking in his ability to perform basic tasks, such as sewing in a straight line. His father insisted he would improve. It did not seem to matter much to the trajectory of his life that he had not done so.

Everything was very settled on that score. Naftaly would take over his father’s business, and with a great deal of luck he would not run it into the ground. He would greet his neighbors every morning, all of whom knew him from early childhood as a man of limited utility, but who would bring him work, anyway, because that was what one did with one’s neighbor’s mostly useless son. It was already too late for him to find another trade and, truthfully, he wasn’t sure he’d be any better at something else. He had few friends, because he was too acutely aware of how much he was tolerated for his father’s sake, and because he did not know what to talk about with other men his age, nearly all of whom were married. He was not especially devout, nor was he keen on drinking and brothels. What he wanted, more than anything, was to be a help to his parents rather than a hindrance, but he’d failed rather spectacularly in that regard.

He would keep shabbat and the festivals, and run his shop until he couldn’t any longer, and like this he would grow old.

Very occasionally, he would think about some alternative path he might have chosen, if he’d insisted when his father had denied him the opportunity to train with someone else. He imagined himself a very good trader of oil, traveling all the way to the sea, with so much spare money that the neighbors would admire him and come to him for help—and he would help. In this other reality, Naftaly was the greatest philanthropist Rimon had ever seen. Men would take his hand in thanks, and he would smile and say something like: “I’m so pleased to have been able to serve you.”

He tried to quash such thoughts, but it was easy to daydream when sewing a hem in a poorly lit room. Perhaps this was why he was such a bad tailor. Better not to wonder about that.

On the bridge, Naftaly vaguely wondered where his father had gotten the oranges.

His father was slim, as was he, neither particularly tall nor particularly short; if either of them had a notable feature, it was their shared inability to grow much in the way of a beard. He offered one of the oranges to Naftaly, who took it with a nod of thanks. He did not say, Thank you, Father, because, his father had told him long ago that one should never give up one’s name in a dream.

“Not even to you?” he’d asked.

“Not to anyone,” his father had said. “Never say your name, or mine, or even call me ‘father’ out loud.”

Naftaly didn’t know if other people had these sorts of rules; if they nearly always dreamt of strangers who were never to learn their names. But occasionally when his friends or schoolmates mentioned their dreams, it seemed like theirs were different. They dreamt of pretty girls. Naftaly had never dreamt of a pretty girl.

He ate his dream-orange in silence. Finally, his father said, “They’re in a state today.”

“A state?” Naftaly asked. His father nodded toward the people rushing across the bridge. They did seem to be in a hurry.

“What’s wrong?”

“Not sure,” he said. “But something is happening, or is about to.”

From the crowd on the bridge, he heard a whisper that rose up like a hiss: La Cacería.

“La Cacería?” Naftaly asked his father. He’d never dreamt of a hunt before; it made no sense for anyone to be hunting in the city, in any case. Did they think a buck was about to run across the bridge?

His father dropped his dream-orange and grasped him by both shoulders. “Wake up,” he said. “Wake up now.”

“What? How?”

The sound of hoofbeats came loud and fast, and two men rode in overland and blocked the far end of the bridge, bringing the crowd to a halt. Both tall: one dark, one with hair that looked dark at first glance but shone red when the starlight hit it. Both were dressed in dark blue. “No one move,” the red man said.

Naftaly’s father grabbed hold of Naftaly’s ear and twisted it. “Wake up!” he ordered.

In his bed, Naftaly sat up with a start. He reached for his ear and found it still tender, then swung his legs over the side of the bed and made his way downstairs to find his father in the kitchen pouring a cup of wine with shaking hands.

“Father,” he said.

“Naftaly,” his father replied. The two never spoke of their shared dreams. Abrafim Cresques, in fact, denied them so often that Naftaly had for a long time thought they were merely an invention of his own imagination.

“Father,” he said. “Please.”

His father set down the wine, still half-full, saying, “Don’t sleep again tonight.”

***

In Toba’s grandfather’s bookcase, there was a map, rolled up, that stretched from Pengoa on one end all the way to P’ri Hadar on the other. When her grandfather’s students were elsewhere, when she was done with her chores and no one was around to see, she liked to unroll it on the long study table and admire it. It had been inked by a master, with details so small you had to put your nose to it to see them all: imagined beasts at the far end of the sea; a cap of snow on Mount Sebah; impossibly tiny ships in the harbor at Merja.

That day, however, the students were there, arguing in hushed tones about the interpretation of one law or another, and how the Rambam said one thing and the Ramban another, yet Moses deLeon has said some third thing, but possibly (or probably) they were all three wrong. Toba wasn’t particularly interested in this argument, which she thought had to do with how hungry one had to be before it was permissible to eat locusts.

If you were hungry enough to be seriously considering it, Toba thought, you ought to just eat them. Fortunately, Toba had never been that hungry. She’d never seen a locust, but she’d heard them described and they sounded vile, with the creeping and the swarming and all those extraneous legs. Anyway, they weren’t supposed to be arguing about this at all. They were meant to be translating some mathematical text from Arabic into Latin, but the dryness of the work seemed to be too much for them, and arguing about locusts was more amusing. “Point of clarity,” one of the young men put in, “are the locusts crawling or jumping?”

They were in higher spirits than usual. Rimon had suffered for two years under a siege from the northern queen, before the Emir of Rimon had surrendered the city at the beginning of winter and gone into exile across the sea. The government had changed, and the city had held its collective breath, but so far, the only significant day-to-day difference was that they were no longer eating the dregs of months-old rationed wheat. The city had fallen back into its old rhythm. In the Muslim quarter, the call to prayer came its usual five times a day. In the Jewish quarter, the shops closed down on Friday evenings. Except now, in the Christian quarter, a bell had been installed in the church, which rang, Toba thought, rather more than was strictly necessary. Still, the inhabitants went about their usual business of life, keeping the occasional wary eye on the workings of the new order. The Muslims had been promised immunity, and the Jews, too. The wind blew from a new direction, but still, the sun rose and set, as it has always done.

While the young men neglected their work and Toba’s grandfather snoozed in his northern-style armchair (the greatest thing ever to come out of the north, he often said), Toba holed up in a corner with the map spread out across his personal desk. Toba traced the outline of the continents with her eyes. So many cities. There were so many cities. Where would she go, if she were to go somewhere? It was a game her grandmother had played with her since she was small. Of course we are safe, she would say. But if you had to flee, where would you go?

The north was full of barbarians, at least until you got to the lands of the Burgers. Then of course there was the issue that some king or other was expelling the Jews every few years, once they discovered that confiscating their property was a useful way to enrich the royal coffers. Petgal, in the west, had so far managed to avoid such behavior, but then you lived with the sea at your back, and that itself made Toba nervous. The south looked slightly more promising, but only just. East was surely better; with the ancient city of P’ri Hadar or the great port of Anab. Farther still were the silk road and the spice ports, where a traveling merchant might have a use for a wife who could write in five languages—even one without a womanly figure or much skill in housekeeping.

The door flew open, and the boys at the table jumped. Toba’s hand flew to her throat; sometimes, when she was surprised, she had the instinct to shout, though she never had. The man who’d burst in was Reuven haLevi, a friend of her grandfather’s.

Reuven cast his eyes around the room at the frightened faces of the young men, most of them too young even to have a beard, and Toba’s blinking grandfather, who was too weary even to stand up.

“What’s happened?” Toba’s grandfather asked in a sleepy rasp; the voice of a man who had seen many things happen, and was not about to get out of his chair for one more.

One of the boys vacated his spot at the low study table and Reuven collapsed in his place on the floor. “I can’t even say, every person in the street has heard a different rumor. Either we’re going to be fed to the lions or driven into the sea, I don’t know.”

“There aren’t any lions in Sefarad,” Toba pointed out from her corner.

“Well, it’ll be the sea, then,” the man said with a wan smile. “I was trying to get to the Nagid’s to learn the truth of the matter, but half the quarter is in the streets.”

The boys pushed up from the floor then, and out through the courtyard, opening the gate out onto the street, which was indeed full of people and a great deal of noise. Several of the people were weeping. All were making haste toward the house of the Nagid; a throng of people, men and women both. No children, though. Those must have been left at home, which meant that whatever was happening, it wasn’t entirely safe in the streets.

Toba’s grandfather said. “Toba, go find your grandmother before this grows any worse.”

Elena was visiting a neighbor a few streets away; her penmanship was so fine she was often called up to write letters for people; even, sometimes, for the rabbi himself. “Go,” he said.

Toba hastened through the door and out onto the street.

From the other direction came a woman wailing openly, her mouth agape as if it were locked that way, in a permanent howl.

Toba picked up her pace, wishing that she could move with some legitimate haste. It would be good, right now, to be able to do more than walk.

It was one of the peculiar things about Toba, and there were several: Toba could walk, but she could not run; she could talk, but she could not shout; and she could write faster—with either hand—than she could speak. If she moved at more than a brisk pace, she would find herself splayed on the ground; jumping, likewise, was impossible for her. And if she tried to raise her voice, it was as if a hand were constricting her throat, and it would be several long moments before she could breathe again. The writing was less of a trouble, though it had vexed her grandfather’s students when she was younger.

Odd things, all of these, and then one more: while Toba slept, she could not dream.

As a child, she’d been the object of torment. The other children had conspired to make her run—by stealing her toys and then fleeing—and then laughed while she fell. Or they’d pulled her arms behind her back until she was forced to call for help, and laughed when she’d collapsed, breathless on the ground.

She hadn’t much cared for other children.

Her grandfather had taken pity on her, and so, instead of playing with the neighbors, she’d spent most of her early days assisting him, sitting in with his students. At first, they’d been charmed by the tiny girl who learned as quickly as they did, but as she became a woman, they’d become less easy with her. Her grandfather had expected marriage proposals; for a scholar, a wife literate in five languages was a boon in free labor, but he hadn’t considered that this was only for a wealthy scholar. For a poor one, well, he would need someone to manage a household, and Toba wasn’t much good at that sort of thing. She was too quiet, too peculiar, too weak. Food often tasted poorly to her, and she ate little as a consequence. She’d been a sickly child, and now she’d become a sickly woman, more than ten years past marriageable age.

Still, she hurried as fast as her sickly legs would carry her; too fast, in fact, and she found herself sprawled on the ground. She instinctively curled in on herself, expecting to be trampled by hundreds of feet, but felt a pair of hands on her shoulders instead.

“Get up,” said the voice associated with the hands. “You’re going to be crushed.”

Trembling, she got to her feet. A young man was in front of her blocking the path of the people who would have stepped on her; no easy feat, since he wasn’t especially large himself. “Are you all right?” he asked.

She didn’t recognize him, which wasn’t a surprise; Toba rarely went out, and unless he trained with her grandfather Toba was unlikely to have seen him. “I’m fine,” she said. “I’m going to get my grandmother,” she added, though he hadn’t asked that.

“Can you get there on your own?”

“I think so,” she said. He nodded and was gone, and she started to cross the plaça to find her grandmother.

Chapter Two

The plaça was entirely filled with bodies, and most of them were dead.

That was Naftaly’s first impression. He reeled and nearly fell, then he blinked the image away. They were not bodies. They were people, living people, swarming the square, all talking at once. He knew why; he’d already heard the bitter choice that had been laid at the feet of his kinfolk… stay and convert, or leave. And not just leave, but leave everything.

People were weeping, and not only the women. Men sobbed openly. Those, he knew, would be the ones who were planning their own exiles. Those who had already decided to stay could not be so bold as to weep in public.

As he crossed the square, the people persisted in morphing into bodies in his eyes. “Not now,” he whispered. “Not now.” But Naftaly Cresques was a bit touched, and always had been. He saw things, generally unpleasant things, and it was not simply a matter of willing the visions away, he had to wait for them to pass. Right now, they did not seem to feel like passing. The fact that he hadn’t slept well the night before was probably not helping.

He felt himself collide with someone, and that seemed to be enough to quiet his mind, and his vision snapped back to reality. A girl. He’d bumped into a girl, who responded by smacking face-first into the ground.

He hadn’t bumped her hard, but she was so slightly built a child could have knocked her over. As he bent to help her get up he realized it was Toba Peres, with her uncovered hair braided like a crown around her head. He didn’t know her, not really, but he did know her history—dead mother, absent father, raised by her grandfather, who had once served the Emir of Rimon and had a small fortune until he lost it, though how he’d lost it was the subject of a great deal of speculation. The pendant that she wore around her neck had come askew, and she straightened it before moving on. It was a hamsa, a palm, with the largest sapphire Naftaly had ever laid eyes on set in the center. It didn’t square with the tales of Alasar Peres’s lost fortune, that pendant, unless he’d spent everything on a gem for his housebound granddaughter.

Then again, maybe it was just a piece of blue glass. In either case, the granddaughter in question got to her feet, Naftaly made sure she was well, and she spared him the quickest of glances before ricocheting off in a different direction. He wondered where she was going, since the Pereses lived on the other side of the quarter. But he had to get home himself, so he shoved his way through the crowd, grateful the people around him were living this time, and made his way back to his house, above his family’s tiny shop on the other side of the plaça. When he got there, he found the door barred.

He banged on it for a few minutes before the housekeeper answered. She was pale and trembling.

“You’ve heard,” he said, and she nodded. She was probably hoping the Cresqueses would choose conversion, because she’d worked for the family twenty years and would lose her post otherwise. But Naftaly knew his father, and it was an unlikely choice. The Cresqueses didn’t have much in the way of property to worry about losing if they left, and Naftaly’s father was devout besides. His mother, oftentimes the dissenting voice in the house, had died last year, and Abrafim Cresques had lost much use for the outside world afterward, reducing his spheres to work, prayer, and mounting frustration at his son’s ineptness with a needle and thread.

Naftaly’s father was upstairs in his small bedroom, and he called Naftaly in. “I need to tell you something important.”

He looked very tired, probably because he hadn’t slept, either.

Naftaly hoped it might be something about the dream-world, but when he entered the room he saw that his father was holding a book. It was small, thick, and obviously old—whatever title might have been on the cover had long ago worn away. The entire volume was encircled by a tape which seemed to be holding it closed. “What is that?” he asked.

“Only a book,” his father said, handing it over. Naftaly took it from him; the cover was ancient-looking and the pages within were yellowed indeed.

“Why is it sealed?” Naftaly asked, fingering the tape.

“Don’t open it,” his father snapped.

Naftaly looked up at his father’s pale face. “Why?”

“No one must ever read it,” he said, taking the book back. “It’s sealed to prevent someone reading it accidentally.”

Naftaly was not sure how someone could accidentally read a book, but his father continued: “It’s a curse. An ancient curse, my father told me, and his father before him. I’m showing it to you because you must know that no matter what happens, we must not lose this book.” With his heel, he pressed on one of the floorboards, lifting the other side. He then tucked the book underneath.

“A curse? Why do we have it? Why not destroy it?” Naftaly asked, because such an object didn’t seem like it should belong to a tailor.

“It’s been passed down,” he said. “No one can remember where it came from, but it’s been ours for ten generations at least, and we’re charged to keep it safe and hidden. It isn’t possible to destroy it.”

“Have you tried?”

“Stop asking questions.”

“Is it—” Naftaly began, and then stopped. He tried again: “Does it have to do with the dream-world?”

Turning to go downstairs, Naftaly’s father said, “There is no dream-world.”

***

That night, Naftaly dreamt of the bridge again, only this time there were no people at all, not even his father. He walked to the opposite end, and found himself in the terraced city where he usually dreamed, still wondering where everyone was; he’d never before dreamt of a world where he was the sole inhabitant. Toward the outskirts, he found himself walking through streets lined with small houses.

Hoofbeats. He heard hoofbeats again, coming from farther within the city. He looked for an alley to step into, and found none, and then a door opened just ahead of him and a tall man, black-haired and wearing a brocade coat, stepped out and hissed at him, “Get inside,” and, when Naftaly failed to move, the man stepped out farther, grabbed him by the collar, and pulled him in.

“What can you be thinking?” he asked, slamming the doorway shut. “To be outside now?”

“I’m looking for—someone,” Naftaly said, managing to stop himself before mentioning his father.

“Pray he’s inside, somewhere,” the other man said.

“What is happening?” Naftaly asked. This was, he thought, the first time he’d managed to speak to one of these dream-people. His father was nearly always with him, and had counselled him to avoid the other people in his dreams at all costs. He’d certainly never been alone with one before.

He bore a passing resemblance to the man he’d seen on the bridge: the man in blue, with deep red hair. But this man’s hair was black, he was lankier, the bones in his face sharper. Besides that, his eyes were doubly strange; not only square, but with irises the color of sunset. He couldn’t recall ever having seen such eyes before, even here. The orange-eyed man replied, “La Cacería has sniffed someone out; I don’t know who.”

Naftaly wanted to ask the meaning of any part of that statement and did not dare, lest he expose himself as some sort of outsider. This man assumed Naftaly understood the nature of this dream place and what happened here, and he was not sure what would happen if he revealed his ignorance. It occurred to Naftaly that this might well be a real person, who in a few hours would wake, just as Naftaly would, and go about his normal day.

Outside, the horses raced past. The other man still had Naftaly pinned between himself and the door. Naftaly closed his eyes until the hoofbeats receded, then opened them to find the other man, still too close, regarding him calmly. He said, “How is it I don’t know you?”

Naftaly said, honestly, “I don’t know.”

The other man looked like he would have said more, but then muttered, “Damnation,” and vanished, leaving Naftaly alone in the house, too afraid to go back out, until dawn came and he woke, and discovered that Abrafim Cresques had died in his sleep.

***

Toba’s grandparents seemed unable to come to an agreement about what to do next.

Alasar Peres had been a translator in the court of the Emir Muhammed VI—father of the emir who had surrendered Rimon to the north—until arthritis had claimed his hands. Now he taught languages in his home to students hoping to make their way to the university. Toba’s grandmother said he’d spent too much time among scholars and it had turned his brain to mush. He was, she said, too optimistic for his own good.

“We’re staying,” Alasar said one evening. It was late, and he and Elena were sitting at the table lit with a pair of oil lamps; ostensibly, he was reading and she was mending a stocking, but in reality both of them were mostly staring into empty space. “We’ll convert, in public,” he went on. “What we do at home is our business.”

“Are you mad? We can’t risk that!” Elena said. “If they come for Toba—”

Toba, who had been translating a bit of Ovid from Latin into Arabic to settle her nerves, looked up at the mention of her name. Alasar gave his wife a quelling look.

“Nobody’s coming for Toba,” he said. “Be quiet.”

“We’re leaving,” she said. “Toba and I. You can stay here by yourself if you want. But we are going.”

“You can’t leave on your own,” he said.

“Try to stop me.”

Alasar’s hoary eyebrows roused themselves, but he made no answer, and Elena sighed. “Alasar, please. How many times do you need to be proved wrong?”

He rubbed at his eyes. “They aren’t letting people take money out of the country.”

Toba leaned forward. She hadn’t heard this part. Elena said, “What?”

“It’s in the edict. No money. No gold. No jewels.”

“The crown is seizing it?” Elena asked.

“Yes! Do you understand? If we go, we lose everything we have left.”

“Yes,” Elena said. “But we live.”

“We can live—”

“Here,” she finished for him. “I know what you’re thinking, you old fool. We’ll live here, until someone decides they want what little you have and starts tapping on the shoulder of the Inquisition. You’ll be up in smoke in a week.”

“What do you think will happen to us if we leave? I’m an old man. You expect me to build a life from nothing? Here, we have a home. I have a reputation, and I can teach anyone who would learn from me.”

“We can go to my brother’s,” she said. “In Pengoa. He’ll take us in. He has space.”

“I have no interest in spending my waning years as your brother’s dependent,” he said.

“Alasar,” she murmured. “If they take Toba…” and then she moved to whispers. Alasar’s head bent to listen, his eyes closed. After some time, Elena stopped talking, and they just sat, staring at the table. Finally, Alasar said, “Very well.”

Toba waited for more of this conversation to unfold, or to be included in it, somehow. When neither occurred, she slipped out of the room and into the courtyard, carefully stepping over the cracked stones in the center that had broken apart in some earthquake long before Toba’s memory. She picked an orange from the tree nearest the gate and weighed it in her hands, looking up to the sky, where the moon was full and seemed very, very close.

She leaned against the gate and looked out at the rows of houses up and down the street, most of which were still burning lamps themselves. Likely every family in the quarter was having some version of the conversation she’d just overheard, though she wondered about her grandmother’s special concern for herself. It seemed odd to her that anyone should think that Toba was in more danger than her grandparents. Toba had no money to steal. She had no friends to inform on her, and she seldom went out enough to attract the attention of… well, of anyone, to be honest. She was, she thought, as safe from public scrutiny as possible. Except for her grandfather’s students, few people knew much about her at all, and she thought it unlikely that those young would-be scholars could make their way into the pockets of the Inquisition.

So why was her grandmother so worried about her, particularly?

Likely she was just being overprotective. Elena seemed to run that way naturally, probably as the result of losing her only daughter in childbirth. And it had been such a strange death, people used to tell Toba, before Elena could chase them away. Penina had been strong, sturdy, and rarely ill; the last person on earth anyone would suspect could die bearing a child. If it could happen to her, said the neighbors, it could certainly happen to anyone—but Toba, for certain, should never marry, because if Penina had died in her childbed, little, sickly Toba had no chance at all. Clearly, they said, she must take after her father. The slime. Whomever he was.

Toba’s parents had been married in Meleqa. He’d been a merchant, and after Penina had died he’d left Toba in the care of her grandparents and gone back to Anab.

It was no wonder Toba had developed a terror of childbirth, and in her heart, she hoped her grandparents would live forever, and she’d never be forced to marry at all. She could stay at her grandfather’s side, translating Ovid and Ibn Sina, forever and ever.

To the south, a light streaked the sky.

Toba squinted to get a better view… it must be a falling star, she thought, except in Toba’s experience falling stars did not travel that way. She’d seen one or two in her evenings sitting outside with her grandfather on warm nights, trying to cool off before bed. Their trails were usually horizontal, or diagonal. This shooting trail was exactly perpendicular to the horizon. And it had appeared to be traveling upward from the ground.

Shooting stars, Toba thought, did not go up.

She decided to get her grandfather and show him, but before she could, the trail had faded as if it had never existed.

Toba put a piece of orange in her mouth, only then realizing when her mouth filled with bitterness that it was still completely green.

***

April was coming to a close, and Naftaly was wandering the streets alone, at night.

This was not a habit of his generally, but ever since the edict and his father’s death Naftaly’s visions had grown worse both in frequency and intensity, and he found that if he kept moving he seemed more able to shake them off. It was the grief, he told himself, though he struggled to call it that. He did not feel sadness so much as numbness. He missed his father, he’d loved his father. But his father had always held him in an infuriating spot that somehow managed to be both suffocatingly close and at arm’s length. Keep to the house, had been his father’s refrain, take over the family business—because I don’t believe you can succeed in anything else—but never ask about your dreams or visions or what any of it means.

His visions were at their worst when he was alone and indoors; at least outside there was the chance that something might jar him out of them. So far, he thought he’d kept his neighbors from realizing how badly he was afflicted. The last thing Naftaly wanted was for someone to a call a physician, who would probably sedate him with poppies, or the rabbi who might call him possessed. He was fine, the great majority of the time. He was not mad. He just occasionally… saw things. Things that weren’t, in the most technical sense, real.

Naftaly supposed that probably many people saw things that weren’t real, and had elected never to bring it up, which is what Naftaly’s father had instructed him to do back when he’d mentioned it as a boy.

It had been a vision of ships, the countryside turned to seawater so real he could smell it. He’d been on board some large sailing vessel, and the rolling of the waves had rendered him nauseated and retching. When he’d come out of it, after perhaps thirty seconds, he’d told his father.

“Runs in the family,” he’d replied over the top of a pair of trousers he’d been stitching. “Don’t tell anyone.”

This seemed to be his father’s answer to most of Naftaly’s difficulties.

The worst problem with these visions was that whenever Naftaly saw something odd, he had trouble telling whether it was real or a figment of his mind. So when he was wandering the quarter under the full moon and saw what appeared to be a falling star shoot up from the ground somewhere outside the city, his first thought was, I hope this doesn’t grow worse.

He waited for it to morph into a monster that ate the moon, or to see a phantom city in the mountains, which he now saw fairly regularly. But when nothing more appeared after a few seconds, he began to wonder if it was real after all, some strange phenomenon of the night sky. He wished, not for the first time, that he’d been afforded the opportunity to study, to make his way to the university instead of preparing to take over his father’s tailoring business. Perhaps then he would have known what that light shooting up from the ground might be.

But that was not to be. The afterimage of the star faded, and Naftaly decided to return home, only to find himself plagued by the worst headache of his life, a pain that started behind his left eye and radiated outward, as if there were something embedded there trying to escape.

Naftaly lurched sideways, a hand over the offending eye, and vomited, and then passed out in the street.

He woke the next morning, victim to the end of a woman’s broom. “Wake up,” she said. “Drunk thing, spending the night in my doorway. Go home.”

He sat up. The pain was gone, but he felt weak, as if he’d been sick. “I’m not drunk,” he said. “I’m ill.”

“Be ill at home,” she said, prodding him again with the broom.

“I’m going,” he said, getting up. “You can put your weapon away.”

“I’ll show you a weapon,” she said, and hit him soundly over the head, leaving him with a mouthful of bristles.

When he arrived home, sometime later, he found the door bashed in.

Excerpted from The Pomegranate Gate, copyright 2023 by Ariel Kaplan