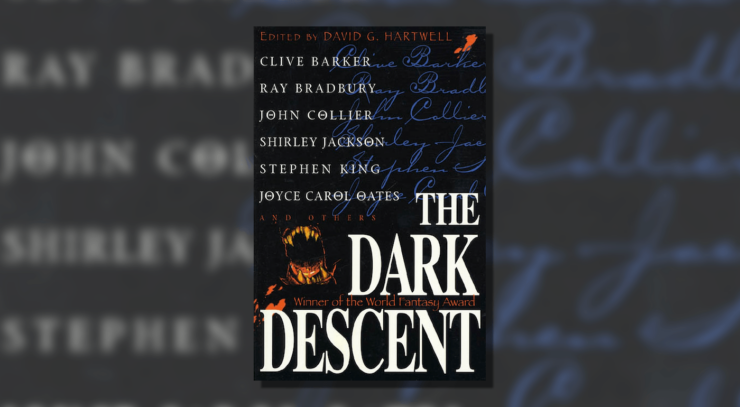

Welcome back to Dissecting The Dark Descent, where we lovingly delve into the guts of David Hartwell’s seminal 1987 anthology story by story, and in the process, explore the underpinnings of a genre we all love. For an in-depth introduction, here’s the intro post.

This article in our series is going to be a little different. Our current stop on the table of contents is “The Call of Cthulhu” by H.P. Lovecraft, a story and author whose legacy have been discussed exhaustively at length over roughly a century of criticism. People much more qualified than I have, at length, discussed horror’s complicated relationship with Lovecraft and his legacy. Chances are, discussing the Lovecraft stories included in this anthology would just be repeating everything already said to some degree. Despite that, Lovecraft is an author who clearly made an impression on David Hartwell. Not only does The Dark Descent quote “Supernatural Horror in Literature” in its introduction, but Hartwell features two of Lovecraft’s stories (“The Call of Cthulhu” and “The Rats in the Walls”) and the work of at least one person who heavily references Lovecraft.

Since Hartwell wanted to edit a definitive history of the horror story, he clearly felt that Lovecraft wasn’t just worthy of inclusion, but integral to the history of short horror fiction. This being the case, I thought it would be instrumental to take a look at why Hartwell thought he was such a worthy inclusion. This isn’t going to be a Lovecraft love-fest, don’t worry—the goal in writing this is to show why he was deemed so important, and in the process demystify one of horror’s most enduring and exhausting figures.

Hartwell’s fascination with Lovecraft lies in how Lovecraft understood horror. To Lovecraft, horror was about emotion and sensation in the reader, evoking dread or uneasy fascination with his tales of contact with the unknown and unnatural. Lovecraft’s ultimate goal with his criticism—to define the shape of horror, specifically in the gothic, supernatural, and weird vein—was similar to Hartwell’s own goal of creating a definitive work on the short horror story. As Lovecraft himself said (as quoted in Hartwell’s introduction):

Atmosphere is the all-important thing, for the final criterion of authenticity is not the dovetailing of a plot but the creation of a given sensation.

Or, put simpler, horror is about a specific sensation, not a set of tropes or rules. It’s unique among genres in that all are welcome as long as you elicit the proper tone—make someone feel weird, unnerved, unsettled, or tell a story that explores those feelings and boundaries, and you’re in. It’s one of the most concrete ways we have to define horror. Lovecraft used that concrete understanding to push boundaries, not just in terms of story elements, but in terms of the stories themselves.

By using familiar structures—underground cities, ancient cults, sinister conspiracies, squid-faced monsters, and gothic horror tropes—and applying them to his own primal fears of death, madness, disease, and pretty much everything outside his own front door, Lovecraft translated those fears for his readers. He also messed around with story structure itself. “Call of Cthulhu” is a nested epistolary work that reads like a very disturbed piece of investigative journalism. “The Rats in the Walls” plays with late-1800s pulp imagery (bestial people, underground civilizations, dark conspiracies among the aristocracy) to create an absolutely twisted story. Even one of his more conventional stories, “The Cats of Ulthar,” takes the form of a folktale. He even wrote an epic fantasy story with “The Dream Quest of Unknown Kadath.” He also set all these things in a relatively open-source universe, being one of the most successful to do so. The “Cthulhu Mythos” is something people engage with to this day, with Lovecraft’s vast works and “things man was not meant to know” providing direct inspiration and reference for a multitude of horror works.

Which leads us, in fact, to how we can decouple ourselves from the grasping tentacles of a man so backwards he thought monarchism was a good idea, and finally move past the leaden thud of “Lovecraftian” works. Despite the praise heaped on his technique and craft, despite his deep and incisive understanding of horror as a whole, it’s high time we climb out of his sandbox. While I certainly have no problem with those who wish to put their own personal mark on or otherwise subvert Lovecraft’s work, there’s so much more to be gained by moving past it. Lovecraft is foundational to modern horror—his understanding and willingness to marry the primal and abstract in a more (for his time) modern style of grotesque are practically the formula for successful modern horror (it’s been used to devastating effect by a number of writers)—but at some point, you stop inspecting a structure’s foundation. It’s high time we made our own mythoses (mythoi? It’s not an easy word to pluralize) and created our own personal versions of what Lovecraft did without using his exact components. It’s not enough to merely “do Lovecraft” just without the offensive parts; eventually we have to move past him and leave him behind.

August Derleth even advised Ramsey Campbell as much, telling Campbell—who started his career writing cosmic horror with Lovecraft pastiches—to develop his own style and voice. The result of that advice—Campbell going on to write a fierce mix of folk horror, modern terrors, gothic horror, all infused with his own brand of disturbing imagery—further enriched horror and birthed a modern master. Numerous others have developed along similar lines without directly drawing on Lovecraft’s work. Stephen King’s unusual suburban gothic nightmares owe a debt to Lovecraft’s conception of horror, but is very distinctly his own work, set in his own world. Plenty of authors are able to build their own horrifying little corner of the multiverse for readers to curl up in by following the formula and pushing the established boundaries of work as they understand it without incorporating one of Howard’s unpronounceable gods or stellar fungi (or any of the numerous people assimilated into Lovecraftiana like Robert Chambers or Frank Belknap Long).

It’s a simple enough formula to digest, even. Define what horror is to you, figure out what fears motivate you on a primal enough level to translate that feeling to your readers. Build your own universe of monsters and ideas story by story. Be unafraid to experiment, whether that means formally or in terms of taking the story places you haven’t seen before, and most of all be flexible and receptive. As long as we keep those things in mind, and ground them in our own attempts to understand and define horror as we see it, eventually we can find our way to our own blasted plains and horrifying monoliths and move forward, leaving Howard’s far behind.

As always, we await your comments. Should we leave Lovecraft behind and build our own universes rather than keep going over the same parts of his? How foundational is Lovecraft to modern horror? And at the end of it all, what’s the plural to “mythos” anyway?

And as always, join us next week when we discuss and define American folk horror through one of its most shining exemplars with Shirley Jackson’s “The Summer People.”

Sam Reader is a literary critic and book reviewer currently haunting the northeast United States. Apart from here at Tor.com, their writing can be found archived at The Barnes and Noble Science Fiction and Fantasy Book Blog and Tor Nightfire, and live at Ginger Nuts of Horror, GamerJournalist, and their personal site, strangelibrary.com. In their spare time, they drink way too much coffee, hoard secondhand books, and try not to upset people too much.

I would recommend checking out Tour de Lovecraft by Kenneth Hite, which has some interesting thoughts on Lovecraft’s oeuvre.

Myth/Myths; Mythology/Mythologies. “Mythos” always sounds to me like a concept that’s putting on airs. Two-Buck Chuck in a Dom Perignon bottle? Something like that. Kind of like how in the past couple decades “World-building” took the place in authorship formerly occupied by “Setting.” C’mon.

I’d also reserve the term (myth) for real-world retired faith systems. For more modern fictional constructs and melting pots, I do kinda like “Legendarium.”

I am pretty sure it is “mythoi”. Going through a “Lovecraft phase” was healthy enough for me, though now his stories are as much the tired default as the musty mysticism he reacted against (don’t get me started on Cthulhu Kitsch). I haven’t been inclined to revisit any of his works in years (let alone pastiche) but I am grateful that he inspired so many authors to create their own original visions of horror. The Gentleman of Providence still gets a kind thought from time to time when I pass by his shelf.

@SchuylerH Thanks for the confirmation! I was struggling with the right plural and then just decided to write it into the article as a joke on myself.

@sitting_duck Hite’s a favorite of mine, especially when it comes to gothic horror. I need to read more of his non-tabletop work.

I would suggest that Charlie Stross has done a good job with his melding of present day technological horror with traditional Lovecraftian horror in the Laundry Files books. Also, earlier stories such as “A Colder War” and “Missile Gap.”

The reference to the HPL tale “The Cats of Ular” omitted two letters from the correct title, which is “The Cats of Ulthar”. This feline kingdom was also mentioned in the Dream Quest of Unknown Kadath.

@6 – Fixed, thanks!

I can’t see leaving Lovecraft behind, but he’s one of many older sources of popular tropes that have been used in derivative works for way too long. Which is just a problem of genre fiction in the current day across the board. Better to be repeating Lovecraft than silly 1960s TV shows like Star Trek and Doctor Who, or children’s comic books like X-Men and Batman, many years after those should have dropped out of sight.

His original insight was the horror of human insignificance in a universe hugely larger than anyone had imagined even a decade or so before he began writing. The discoveries in astronomy of that time vastly expanded the scales of time and space beyond what most scientists had expected, and made it impossible to take a human-centered view of creation seriously. Lovecraft and existentialism are both offshoots of this new realization. Now the way he wrote this into his stories could be clunky and was often pulpish, but he was able to convey it (sometimes quite effectively) using a mishmash of tropes from Machen, Wells, Blackwood, et al.

It would be great if we could have fewer recycled tropes and “retellings” of old works and publish more original fiction, difficult as that may be. Without necessarily leaving any of the cult favorites and hoary classics wholly behind.

One characteristic of Lovecraftean horror that is worth preserving is the accompanying ‘sense of wonder’ that HPL allowed into his “cosmic” stories. Those non-Euclidean geometries, unfathomable temporal depths, and vast, stellar abysses add a lot of fascination to his Mythos, Some of the recent Lovecraftean practioners, such as Ruthanna Emrys, have re-focused the reader’s attention onto those more compelling aspects of their Mythos (or Myth-oid?) works.

Just wanted to mention that King’s Jerusalem’s Lot is about as straight of a Lovecraft pastiche as they come.

Thank you very much for your kind comments about my stuff! For me what remains crucial about Lovecraft’s work is his care with structure and with modulation of prose – indeed, I think “The Rats in the Walls” can be read as a tale about language – and the way he tried out all the forms of horror fiction (or the weird tale, as he styled it) that he could achieve, so as to test them.

@8/Paull Connelly

The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun. There’s no such thing as “original” fiction, just fresher ways of mixing those recycled tropes.

I don’t think there’s a need to move beyond Lovecraft. As someone who is immensely inspired by his work I believe his words and worlds are still valid ground for writing. His view of humanity’s role in the universe remains relevant as we face a collective nihilism and apathy towards our cosmic roles. There are some fears which are deeply ingrained, the fear of the dark and the fear of the unknown being the most prominent I can think. I think any aspiring horror writer should read the fundamentals (Shelly, Poe, Lovecraft, Barker, etc) and then make their own mark by understanding what scares them most. I don’t think we should ‘move on’ from any writer, we should understand why they are the fundamentals and strive to create our own work.

@12 rickarddavid: Supposedly there are only 30 basic plots for fiction stories, so yes, there will always be some recycling. But if books like The Shadow of the Torturer, Lavondyss, China Mountain Zhang, and The Fifth Season were recycling tropes, those tropes certainly were either very uncommon or totally skewed into a wild conformation. That’s because Wolfe, Holdstock, McHugh, and Jemisin have the talent to come up with highly original works. Even something that’s been endlessly copied like Neuromancer, which borrowed heavily from noir mysteries, put everything into a world that only a handful of other writers were even imagining. The first author to recycle some tropes in an original way then creates other tropes which (as with Gibson’s work) get used over and over by other writers.

Maybe retellings of Theseus, Medea, Jason, Circe, et al., were relatively uncommon in the 1950s, but now you can hardly visit a bookstore without tripping over a pile of them. And let’s not get into the sword-wielding princesses who must have red hair like all spunky heroines do and the sassy thieves who spark revolutions before breakfast each day rather than end up in jail. (Okay, I’m exaggerating here!)

Check out Winter Tide for what can be done with subverting Lovecraft.

Winter Tide is spectacular. It’s a mashup of the intelligent species from Lovecraft, the Deep Ones as a persecuted racial/religious minority, and a theme that no one has clean hands.

There’s some race-neutral (I’m pretty sure) Lovecraft-influenced sf. China Meiivile’s “Details” is about the lurking stuff you’re better off if you don’t notice (but what if you can’t help noticing it?) and “The Last Feast of Harlequin” by Ligotti has the feel of a small scale Lovecraft story without any specific details from the mythos.

For another fresh take on the Mythos, there’s the Weird of Hali series, by John Michael Greer, along with 4 independent but related novels. The “monsters” are the good guys, some anyway, and humans learn to live with them, including those as far above humanity as we are above microbes. Quite skillfully written, to my ideas–bits from disparate stories woven together so they work, colorful scenes, and good portrayal of women characters. Highly recommended. Oh, and The Dream-Quest of Velitt Boe, by Kij Johnson. Her “The River Bank” is also great, but that’s a whole different mythos…

You can’t even escape Lovecraft in your own attempt to escape Lovecraft.

No one can escape Lovecraft because he did something that no modern author is willing to do, despite his flaws (which every human has to the point that there flaws you have and are not even aware of).

Which is to directly say that his works have no copyright and are available for common use.

Speaking of lack of copyright, there are a lot of Sherlock Holmes/Lovecraft mashups.

Are there Lovecraft/Tolkien mashups? (Yes, I know Tolkien is in copyright. His influence is still all over the place.)

As someone else mentioned, I cannot leave Lovecraft behind. Many forget his voluminous corpus of correspondence which few read. Moreover, he “edited” (more like rewrote) a great many amateur authors’ works.

For me, Lovecraft was a prophet. Make of that as one wills.

If someone’s perfected something than why move past it? I haven’t seen an original idea in almost 60 years. Everything we do now is just improving what we already know, but horror? You can only be so unique in the horror genre and with master Lovecraft dying so young (unfortunately since reality has gotten so much more horrifying) we need more to follow in his footsteps so we can at least get well written and extremely thought provoking and inspirational stories. Accept Lovecraft as a God AND WORSHIP HIM!!

@20: Some of the bits about the dwarves having dug too deep in Moria could be see as having a bit of a Lovecraft vibe.

I believe well the most important aspect to take from Love Craft’s body of work and his approach is the intent, otherwise we wouldn’t be talking about him 86 years after he died. His specific styling—specific enough to him that he’d be considered the father of—is Existential Horror, or the idea that we, as humanity, are of such little significance that our lives, collective or individual, are meaningless. That true dread is coming to decisive conclusion the mortal coil is naught but a fringe attachment the universe has no concern with.

Whether you care for his writing or not it’s come to inspire some of the more impressive works over the years dealing in keen detail with ideas that can be traced directly to him, such as John Carpenter’s the Thing, Hidetaka Miyazaki’s Bloodborne, and Clarke/Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. The approach is translated based on the medium and author, but the core idea still remains: ours is not a life of importance.

The chief criticisms of Lovecraft are usually his xenophobia, and his antiquated vocabulary.

To the first I say, critique the art, not the artist. It’s not as if a man long dead could be “canceled”. The infamous cat was named after *his own cat*, that he had as a boy. Besides which, he’s irrevocably embedded in the foundations of horror and science fiction to such an extent that ever truly “moving past” him is a moot point.

To the second, we don’t abandon Liszt or Beethoven because the music is harder to reproduce. His prose is beautiful; flowery, and ornate. The literary equivalent of hand made, antique, lace doilies, and carefully carved Victorian woodwork. That some people find it difficult to read is more of criticism of modern literacy than the stories themselves.