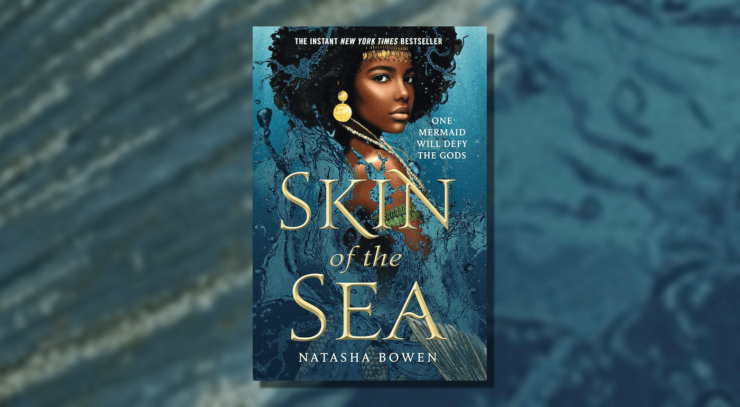

The best fantasy builds on works that came before, weaves sources together in ways both new and traditional, and transforms them into something entirely the author’s own. In Skin of the Sea, Natasha Bowen engages explicitly with Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid. She takes the bones of the story—the seven mermaid sisters, the youngest with her rebellious spirit and her fascination with humans, the ruler of the seas whose commands she is bound to obey, and the price of resistance: both physical pain and literal dissolution into a drift of sea-foam—and gives them a whole new life and home in West Africa.

The result is a classic fantasy with a fresh and refreshing take on the original fairy tale.

Like Rivers Solomon’s The Deep, it builds its world on the history of the Middle Passage, the slave trade out of Africa and into the Americas. It’s set at the very beginning, in the fifteenth century, just as the Portuguese traders began to trade in human cargo and ship it westward.

Solomon’s world is more science-fictional, trending toward Afrofuturism. Bowen’s is a combination of fantasy genres: historical fantasy, quest fantasy, epic fantasy. Her mermaids live in a world of gods and supernatural beings, subject to the whims and the will of the divine. She has a gift for description, for evoking the full scope of her world and her characters. They’re beautifully and vividly described, in the rhythms and the idioms of oral as well as written storytelling.

This is a story. Story it is.

The protagonist, Simidele, was born human, taken captive by white raiders, and flung into the sea from one of their ships. She was rescued by one of the four hundred Yoruba gods or orisas, Yemoja, the mother of orisas and ruler of waters.

Out of grief and compassion for the humans who suffer so terribly at the hands of the slavers, Yemoja has created seven Mami Wata or mermaids, of whom Simidele is the youngest. It’s their duty and purpose to take the souls of those who died on the passage, to capture them in a sapphire that each Mami Wata wears, and take them back to Yemoja. She in turn will bless them and guide them into the afterlife.

The Mami Wata are classic mermaids; as Bowen describes them, they’re pretty much identical to Disney’s live-action Little Mermaid. They have beautiful fan tails in exquisite colors—Simi’s is rose and gold—and scales that run up past their chests toward their human arms and faces and their luxuriant hair. They breathe both air and water. When they come out on land, their tails transform into legs and their scales into clothing, a wrap that covers them from chest to feet.

The transformation is almost immediate, and can persist for as long as it needs to. They will always be drawn to the water, whether sea or river, but they can survive away from it. The price of that survival is pain in the feet and in the joints of the legs, which increases the longer they remain on land. Walking is difficult and does not grow easier with time, but they can and will do it if they must.

They are apparently mortal; it seems they may live a human lifespan, though we don’t get much detail about that in Skin of the Sea. There may be more in the sequel, Soul of the Deep. The first volume has plenty to do with contentious orisas, teenaged rebellion, doomed romance, and an ultimate, terrible, but inevitable sacrifice.

When we first meet Simi, she’s only been a Mami Wata for three months. Unlike the other six, she hasn’t completely embraced her fate or her purpose. While she’s in the sea, she loses the memory of her human life, but she clings to such scraps as she can retain. She goes frequently to Yemoja’s island, where she can return to human form and retrieve a few of her human memories.

This can’t last, and she knows it. But she keeps doing it. She can’t be truly human again, she’s lost that in becoming what she is, but she wants to remember. She tries to remember.

And then, immediately after Yemoja has admonished her to stick to her duty, she comes upon a human who has been cast into the sea—and who is still alive. She should let him die and take his soul. Instead, she saves his life.

In so doing, Simi defies the will of Olodumare, the Creator. Orisas, and their creations, are not to interfere in the affairs of humans. Yemoja skated close to the edge with the creation of the Mami Wata. Now Simi has put both herself and Yemoja at risk of divine punishment.

Simi is bound on a twofold quest: to seek out Olodumare and beg his forgiveness for herself and Yemoja, and to return the boy she rescued, Adekola, to his home and family. Kola claims to know the whereabouts of the babalawo, the high priest who keeps two rings that allow their wearer to summon Olodumare. If Simi will help him get home, he will help her obtain the rings.

Buy the Book

Infinity Alchemist

Kola has an agenda of his own, and a family secret that ties in closely with Simi’s quest. Olodumare communicates with the world of mortals and orisas though a powerful orisa, Esu, who is both a messenger and a trickster. Esu also has his own agenda, which may doom Simi’s quest and destroy everything both she and Kola strive for.

Simi’s journey takes her from the deeps of the sea to Yemoja’s island to the coast of Africa, from the land of the dead far beneath the sea to Esu’s island realm with its volcano and its enchanted palace. She meets creatures both natural and supernatural, human and otherwise.

Bowen knows Northern European lore and legend very well indeed, and matches it with African parallels. Just as she gives us mermaids as Mami Wata and the ruler of the sea as the orisa Yemoja, she introduces us to the Senegalese analogue of the Fae, the tiny and benevolent Yumboe. We meet the Ninki Nanka, a dragonlike river monster, and the African version of the unicorn, the Abada, with its turquoise eyes and its two spiral horns that can cure all ills.

Simi’s journey is as much a journey of self-discovery as a quest to save herself and her world. She cannot love a human with destroying herself, but her love for Kola grows as they travel together. She dreams of being human; as her memories come back one by one, we learn who she was and where she came from and what happened to her.

We also know that she died to the human world. She’s a supernatural creature now, a child of Yemoja. She belongs to the sea.

At the end, she makes the only choice she can. But this is only half the story. I’ll be there for the other half, up there on my TBR pile, just as soon as time and commitments allow.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks. She’s written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.