Note from the blogger: Chainsaw Man is an ongoing series with a devoted fanbase, but for the purposes of the article I will be discussing only the first season of the anime. There will be no spoilers beyond that.

When I was a sophomore in high school, my Life Skills teacher presented our class with the paradox of selflessness. She asked us whether there was any such thing as a selfless act, and informed all those who raised their hands to talk about loving family members or public service workers or soldiers that those people were also, arguably, fundamentally selfish: “Every kindness could be seen as the selfless person stroking their own ego, meeting social expectations, or manipulating others with their kindness.”

Now, at the time, I outright disagreed with this pessimistic worldview, not in the least because the same Life Skills teacher had also decided that the best way to teach Sex Ed to a class of public high schoolers was to tell them that cohabiting before marriage is living in sin and abstinence is the only way forward.

But the paradox did stick with me, unlike her other bullshit. I’ve always been a cynic, and kids these days? Well, naturally they have plenty of reasons to be cynical, too. The world presented to teens today is rife with devastating climate change, shitty job markets, inequality, low wages, unaffordable housing, another spike in global fascism, and a healthy garnish of the highest reported rates of mental illness in modern history. Frankly, the future feels fairly fucked, and it was fucked long before today’s teens were born. So who can blame them for being apathetic about, well… everything?

And while there are endless studies delving into the psychology of growing up in the modern world, maybe every generation has had similar feelings. And anime, for the past half a century and change, has always been there to confront those feelings. Evangelion for the ’90s teens, Death Note for the emo aughts, Attack on Titan for the college kids of 2013, and now? Well, today’s angry youth are perhaps the most fortunate of all, despite being possibly the most doomed, because they get Chainsaw Man.

Chainsaw Man is a masterpiece for so many reasons, both artistically and conceptually, but it is undeniably brutal. It understands how screwed the planet is, but is inexplicably hopeful, too. It presents its traumatized cast of young people as not just incredibly violent, but capable of beautiful growth.

A Boy and His Chainsaw

For those unfamiliar, Chainsaw Man is a fantasy-horror shonen series set primarily in an alternate version of modern-day Tokyo. In this reality, monstrous creatures called devils are a constant plague on society. Each devil is the personification of some concept or object; there are tangible things like Tomato Devils and also Sea Slug Devils and Katana Devils, but also intangible concepts given shape, such as Curse Devils and Eternity Devils. Essentially, the more fear the namesake of the devil instills, the more powerful the devil, because most devils feed on fear.

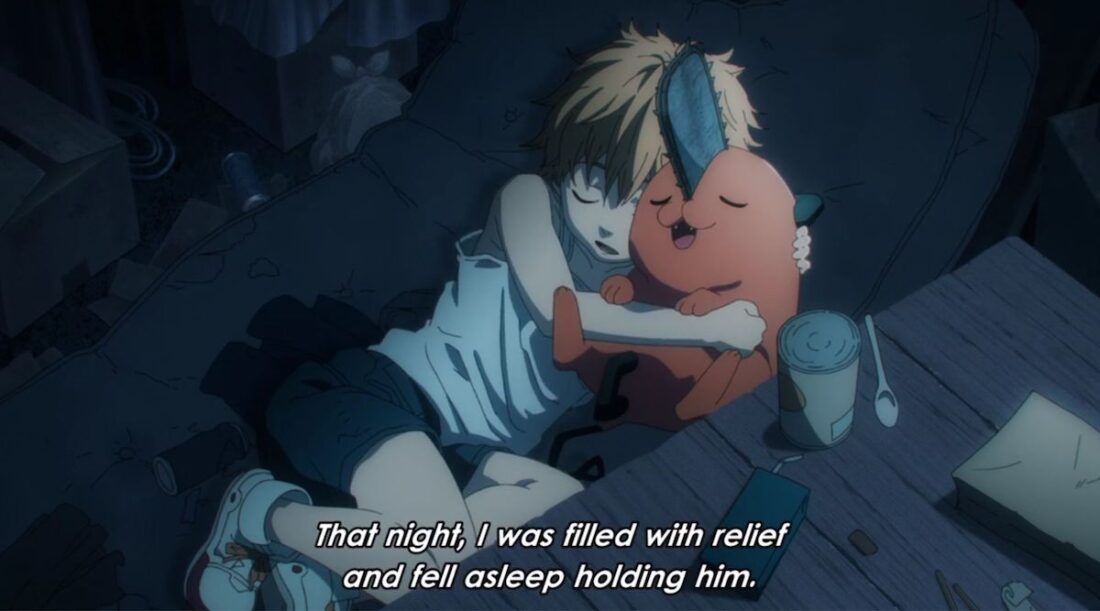

Yet when the Chainsaw Devil appears before our bedraggled protagonist, Denji, who is then only a child standing at his father’s grave, the devil looks almost docile, a wounded dog with a blade jutting from his forehead. Denji gives the devil a name, Pochita, and presents it with a contract, offering up his blood in exchange for its loyalty. Blood heals devils, and blood is binding, and Pochita takes a bite.

Aided by his beloved, sharp-edged pet, Denji somehow makes it to 16, living in a shack and hunting devils in a failed effort to pay off his dead father’s debt, dreaming of one day eating strawberry jam and fooling around with a girl before he, inevitably, dies at the hands of a devil or of the same disease that killed his mother. Denji has already sold a kidney, an eye, and a testicle to afford his meager lifestyle.

But inevitably he is killed by a devil he knows, and it is then, after Denji is literally decapitated, that his pet chainsaw sacrifices itself to save him. Pochita fuses to Denji’s corpse and turns the protagonist into a thing that is neither human nor devil. Soon thereafter, Denji is recruited to work for the public devil hunting bureau.

Thus the eponymous Chainsaw Man is born, though it’s worth noting that Denji is not a man at all, but a boy, and a very damaged one at that. But mangaka Tatsuki Fujimoto has a dark sense of humor, and since Denji has never had a childhood, so maybe the name suits him fine.

Denji, Heartless and/or Heartfelt

“You’re obedient like a dog,” one of Denji’s yakuza abusers says, after he pays the desperate teen 100 yen to swallow a cigarette. In a prime example of the series’ hallmark brilliant characterization, the moment the abuser turns his back, Denji spits the cigarette out.

Already Denji, though admittedly a guy with low expectations and no education aside from what being a devil hunter has taught him about cutthroat slaughter, is more than he is assumed to be.

The irony is even Denji does not think of himself as human, and not only because he lost his mortality and his heart when he fused with his beloved Pochita. Denji’s internalized loss of personhood started much earlier.

In the last quarter of the first season, after a devastating confrontation leads to the demise of several of his devil hunter colleagues, Denji realizes he feels no grief. He cannot understand his own lack of reaction, and assumes it is caused by the devil that has replaced his heart. He mulls it over for a brief moment, then shrugs, because worrying won’t help.

But Pochita, while a devil, was far from heartless. Pochita was shown to be a more empathetic creature than most in the series, willing to sacrifice himself for an orphan boy’s dreams. If Denji lacks a heart, it isn’t Pochita’s fault.

Denji, my guy, you spent your entire childhood in a shack, selling your organs to afford breadcrumbs and slaughtering monsters to survive. Friendless, abused, and alone apart from a sentient chainsaw, who the hell would develop a sense of empathy? It is Denji’s humanity that has left him permanently dissociated. That’s trauma, folks, deep and unaddressed, and possibly also a hardwired personality disorder.

When Denji joins the bureau, he is given a home and all the jam he could want. For the first time in his existence, this kid is comfortable enough to climb a few feet up Maslow’s Hierarchy and engage in actual self-reflection. So what if he finds himself empty? At least he finally has a cup…though it’s anyone’s guess whether he will fill it or shatter it.

Aki-Kun and the Insanity of Persistence

Madness is a motif throughout the series, an addendum to the apathy that helps keep the main protagonists alive. The older members of the bureau say time and again throughout the series that the only devil hunters that survive are the crazy ones.

But Aki, Denji’s assigned devil hunting partner in the bureau, as well as his unwilling roomie, is far from crazy. He is described by another character as “cool, generous, and kind,” and therefore doomed. In most other shows, Aki would be the lead protagonist. He is the only level-headed character in the entire cast, and his motives for fighting are pure.

When he was a child, Aki’s entire family was destroyed by the Gun Devil in an instant. Aki has every reason to fight, and he knows what he is risking and why he is risking it, and vows to avenge not only his family but all of mankind. Aki is a good person—a ludicrous thing to be, given the circumstances.

So Aki could never be the hero in this setting, because heroism cannot prevail in a world where devils break all the rules. Aki knows this, but remains good even though he knows goodness will ultimately fail him. From an audience perspective, however, Aki is essential. Without Aki’s presence, the first season might crumble under the weight of its own manic characters. Every series needs an anchor.

After the demise of a beloved peer, another bureau member asks Aki whether he will quit or continue pursuing his futile quest to destroy the Gun Devil. Aki doesn’t hesitate. “My partner and my family are dead. How could I ever quit?”

But what kind of sane person chooses death? In a world of devils and fiends, being moral is another kind of madness. Aki truly is selfless (suck it, high school Life Skills teacher!). Every time he draws his katana, the devil he has contracted with steals more of his life, and that rarely stops him from drawing it.

When Denji is first assigned to Aki’s team, Aki protests. “We can’t afford any more weirdos!”

Welp. Don’t look in the mirror, then.

Power, Grime, and Grit

It is hard to think of another shonen show that treats its male and female characters so equally. Not kindly, but equally. In the near future, I hope to write an entire article on the women of Chainsaw Man, because damn, are they wonderful.

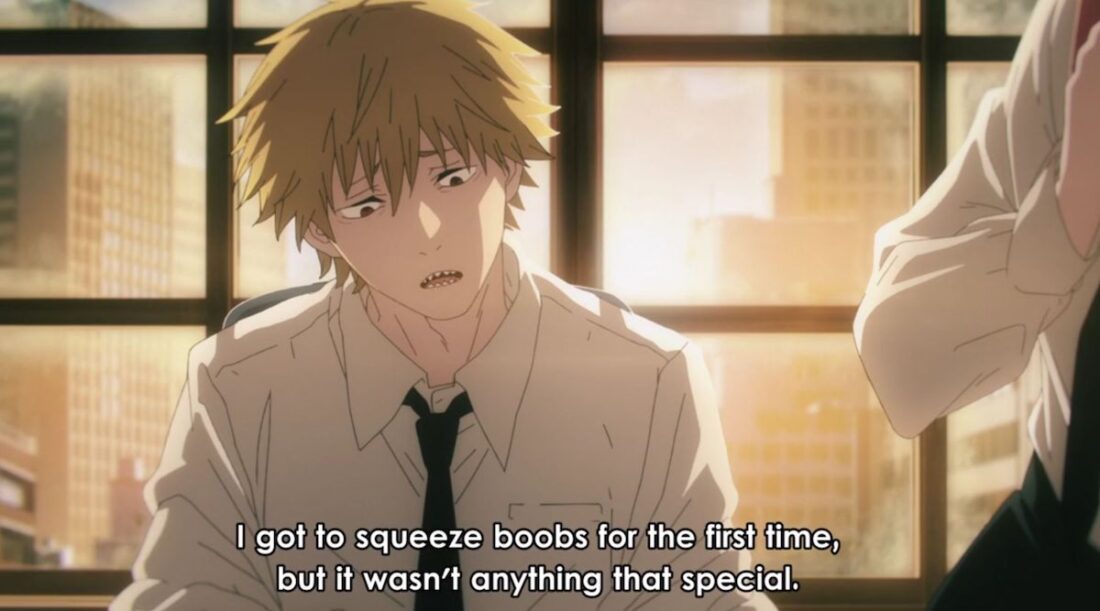

So many anime are guilty of abusing fan service for the sake of comedy or smut, but Chainsaw Man hits different. It doesn’t shy away from the reality of what an adolescent like Denji might want, but it also does not romanticize it. The women around Denji learn pretty quickly that he can be easily manipulated because, well, he’s horny and inexperienced. They have learned that sexuality is another tool at their disposal, a token that can be bartered to make headway in a difficult world.

For Makima, the terrifying devil hunter who has taken in Denji as her “human pet,” that means promising him sex should he do the impossible and kill the Gun Devil. For the blood fiend Power, this means promising Denji he can touch her boobs if he saves her cat.

And while there is so much to say about Makima, this is an essay for the kids, and Power deserves all the attention fans have given her. Power is a fiend, which means she is not a person, but a devil that possesses a corpse. In her case, Power can manipulate her blood and use it as a weapon, and she has possessed the corpse of a teenaged girl.

Power is ruthless, delighting in bloodshed and pain, forced to work for the bureau or perish at their hands. While Denji’s apathy stems from a rough, human lot, Power’s apathy is a feature, not a bug. Power is a wild card, serving a desperate organization as a type of experimental weapon. She has every reason to loathe mankind.

But Power is also a cat person, and an aspiring Nobel Prize winner (spoiler: she really, really isn’t bright enough to win one), and a fantastic fighter. She is as blunt as she is ruthless, and, possibly most delightfully, she is never presented as a romantic interest. She’s another of the misfits, a murderous creature with her own agency. Is it any wonder she’s so beloved?

Also, let’s applaud one of the best aspects of this fiend: Power is gross. She clogs the toilet, she refuses to bathe, she laps up blood and picks her nose. All too often, female characters are resigned to being beautiful. But Power is a mess, and doesn’t mind being a mess. And holy shit, I think a lot of girls, neurotypical and neurodivergent and straight and queer all, really needed to see that in a lead character. Power doesn’t care for people or society or expectations at all, but she really loves her cat. I think a lot of us disillusioned trash goblins can get behind this sentiment.

Numb Characters, Numb Audience

Hyperviolence and anime are old bedfellows, and while this has often inspired a fair amount of controversy for the medium, fans know that in the hands of superior storytellers, violence can serve a variety of purposes.

In the case of Chainsaw Man, there’s no denying that the violence is gratuitous. The protagonist is decapitated in the first episode, for fluff’s sake, and then returns to life as a monster with chainsaws for arms, and a chainsaw for a head for good measure. Right away, the audience knows what they’re in for, and once the initial shock wears off, the gratuity actually feels essential to the storytelling.

Watching Chainsaw Man, I was reminded of the first time I watched Peter Jackson’s horror cult-classic Braindead (Dead Alive in some countries), a movie that aspires to be as disgusting as it is funny. As in Dead Alive, the violence in Chainsaw Man is tinged with humor and often incredibly creative. Denji is a demented Spidey, throwing zingers as he delights in burying his whirling blades in the skulls of monster after monster. Like the characters themselves, the audience soon sees nuances in the onslaught. And the point here is as galling as it is familiar; who in the modern world has not felt desensitized to violence? And, if violence in this world is unavoidable, can’t it at least be fun?

That’s a dark question to pose, but we live in a world where school shootings are a weekly occurrence. People these days, in reality and in this show, are given few options, and none of them are to live in a peaceful world. While in reality we are resigned to cowering, protesting, weeping, or, all too often, ignoring the state of things in order to cope, these kids have been given another option: Reclaim the violence.

Denji and company take command of violence, and use it to help them shape their warped futures. It’s a unique middle finger to give a condemned planet, but weirdly empowering to watch, too.

When Denji shoves a blade into the head of a monster and declares, “Your blood tastes like nasty ditchwater, but drinking it while looking at your suffering faces… it’s like having strawberry jam!” I think we all kind of… get it. He’s sticking it to the man by sticking it into the monsters, amen.

Humble Dreams Are Dreams All the Same

Some say that young people don’t have the ambitions they once did, or that the ambitions they have are just unrealistic; you probably aren’t going to make a living on TikTok, former sad beige child. But frankly, what used to be realistic is far from it, so I say let the kids have their dreams.

I was born in ’89, and boy have I learned to lower my expectations. It would be enough, we millennials and younger say, to have a place to rent and the ability to travel, and maybe healthcare that doesn’t kill us or ruin us financially. It would be enough, we say, to live a life where a single emergency won’t set us back for a decade.

We are far past the point of judging others for their dreams, however misguided.

In Chainsaw Man, the situation is even more dire. Aki has his noble, impossible dream of destroying the Gun Devil, and many of his peers share that one. Power? After her cat is rescued, she has no goals, really, apart from surviving, being on the winning team and enjoying bloodshed (oh, and the Nobel prize). And Denji? Well, at first he just wants to eat strawberry jam, and later he just wants to touch a boob, and later he wants to kiss someone he actually likes. There’s nothing noble about his dreams, and he never pretends otherwise.

But gradually, as Denji survives and he learns to hope for more from the world, his dreams grow infinitesimally larger. Moving goalposts are, in his case, a sign that he is developing as a person. Soon enough Denji resents having to defend his small, petty dreams. If his motive for fighting is a french kiss, well, who cares, so long as the devils get dead?

As he declares to an enemy mid-battle, “If I defeat you, that means my dream of touching boobs is better than your noble, lofty dream!” It’s hard to argue with any of Denji’s would-be logic at the best of times… but damn he is philosophical by accident sometimes.

Contracts, Consent, and the Complexities of Friendship

Look, these dumb kids aren’t good at making friends. And why would they be? Making friends isn’t a valuable skill in the Chainsaw Man universe. However, they are very good at making contracts. And, I want to holler at said dumb kids: that’s the same damn thing!

None of these characters know how to live a life that isn’t transactional. We’ve gone over the things Denji will do to protect a future that features strawberry jam; Aki gave up the bulk of his lifespan to enlist the power of the curse devil. On a more mundane level, the devil hunter Himeno tells Denji that she will help him get with Makima if he helps her get with Aki.

In a world so chaotic, making deals makes a lot of sense. We learn that when a devil makes a contract, they cannot break it, lest they die. Only contractual agreements have a tangible sense of power in this world, and so many people feel powerless. These characters can only hope that making contracts in place of friendships will mean those connections can’t be broken.

Interestingly, this contract-based society also ties inextricably to an underlying respect for consent. Power tells Denji he can touch her boobs if he rescues her cat. He never once considers that he could touch them otherwise, and the show never once presents nonconsensual interactions as a possibility. This idea reinforces the notion that not only does Denji retain his humanity, but also that even in this devil-ridden world, some things are sacred. Consent being among them is, frankly, refreshing, especially given how often other shows have made a joke of the concept.

Eventually, contractual obligations, be they social or literal, can alter the parties involved. Agreements develop into habits and then into deeper understandings, and those understandings are a type of bond that’s a lot closer to friendship.

Somehow despite the apathy and gore and death, despite characters who think of themselves as irredeemable, a buried current of affection begins to connect them, and it becomes a strange sort of goodness. And sorry, questionable Life Skills teacher of my youth, I don’t really care if that affection originates from self-preservation. It’s a good thing.

After spending days slicing up a regenerating monster in a hotel hallway and dying dozens of times in the process, Denji and other bureau members, several of whom tried to sacrifice Denji’s life for their own in the struggle, attend a nomikai that should be awkward. But Denji holds no grudges, and when he mentions that he is only 16, the first thing a senpai says is, “Oh, no! You haven’t been drinking, have you?”

Denji grins and holds up his glass. “It’s tea!”

Because living well might be a contract, too, and these characters, for all their blatant faults, still try to keep some of society’s basic promises, despite the world breaking every one of them. The kids have been forever denied a real education, family, stable homes, personal agency, and safety, but they still can’t help but stumble into remarkable displays of human decency.

And damn it, isn’t that a beautiful, optimistic way to interpret a much-beleaguered generation?

I’d love to hear your thoughts on this gem, and any other series that resonate on a similar level. Next up I’ll be writing about The Eccentric Family and then Delicious in Dungeon, and I hope to be writing a column every two weeks starting in August! Suggestions and conversation are encouraged!

Also, fun bonus: I have been to two different iterations of the Chainsaw Man pop-up cafes here in Japan, and at the first one I drank Pochita as an orange slushie. I am paying the Pochita tax and sharing evidence of this here.

In this article:

- Chainsaw Man (MAPPA, 2022) Available via Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Hulu.

Up Next:

- The Eccentric Family (P.A. Works, 2013-2017) Available via Crunchyroll, Amazon Prime, and Hulu.

- Delicious in Dungeon (Trigger, 2024- ) Available via Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Hulu.

- Frieren: Beyond Journey’s End (Madhouse 2023-2024) Available via Crunchyroll and Netflix.

Love this!! CSM is such a rich text for analysis. Definitely curious about the taste of a Pochita slushie?

If memory serves, it was tangerine sherbert! And later at the second cafe, I had a Pochita curry burger. It was cute but a little cold and sad, like real Pochita.

You’re so right about this being a rich text. As I was writing this I realized I could write a damn book on this series and still have more to say. And that’s without the manga and subsequent story! Really something else. If people engage with this article maybe I can pitch a follow-up in the near future!

Do you have any favorite aspects of the series?

I love how the story presents itself as a typical shounen, and then reveals itself as a horror playing on shounen tropes. Fujimoto’s exploration of how terrifying it would be to be Denji’s situation, as a young boy being taken of by a system willing to exploit him, is really masterful to me! He thinks all he wants is a girlfriend – which is what he is promised – but what he really needs is a home. :(

Anyway, I’d love to hear more of your thoughts on the series in the future!

Thanks for this. I would never have checked CSM out but now I will definitely give it a look. Can wait for your take on Delicious in Dungeon :)

I think people assume (with good reason) that CSM will be another edgy, violent shounen action series. Which…those series can also be great, and CSM is partially that. But it is also a lot more, and sort of sideswipes you with incredible philosophy and characterization before you know it, and it is so far from predictable. These characters are so painfully, unexpectedly human, even the nonhumans, and it sort of takes my breath away sometimes.

I am excited to binge Delicious in Dungeon and take notes! Will it make me hungry?

Tell me your favorite CSM character and why it’s Power.

beautiful analysis! I have been thinking of watching/reading chainsaw man for a while, but this is really making a good case for it. I love good characters and character development and you made a great article analyzing them

I can’t recommend it enough! Thank you!