Content Warning: Mentions of graphic body horror within the context of an action figure line, discussions of cancer, 9/11, and bigotry.

I.

They bleed.

Hanging there, dangling from pegs. Blood pooling beneath them. Maybe. I don’t linger long enough to find out. I hate horror. I hate horror like I hate flying. It’s not the flying; it’s the crashing. The consequences. I’m not supposed to look at horror. What if the people who told me not to look caught me looking? That’s what I’m scared of. The ones who aren’t bleeding. The ones who smile and assure you everything will be all right if, if, if… I’m only a kid, but I’m learning that horror is relative. Sometimes the ones who aren’t bleeding, actually are.

And the ones who are, actually aren’t. Later, I’d understand they were not, in fact, bleeding. Sure, it looked like bacon strip skin flaps revealed gaping chest wounds, and limbs were flayed to reveal muscle and bone screwed into metal braces, but they were just plastic. Contained within bubbles hooked onto metal dowels protruding from toy store walls.

These are the action figures of McFarlane Toys’ Clive Barker’s Tortured Souls line. They can’t bleed. They have no flesh. But, through paratextuality and play, they are fleshed out, waiting to walk with me on my journey through horror.

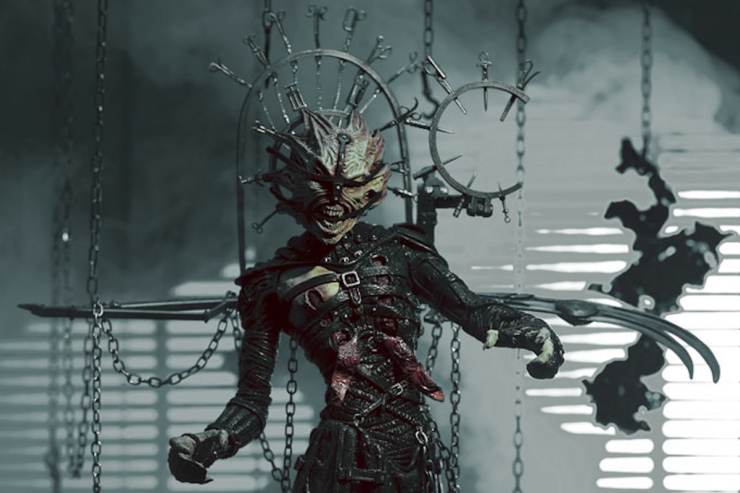

The first wave debuted at Toy Fair, the annual toy trade show in New York City, in February 2001. Six half-foot-tall figures comprised the line, all design collaborations between horror writer Clive Barker and pop culture creator Todd McFarlane. Barker, informed by his legacy of Hellraiser, crafted characters who leaned into body mutilation, S&M, and mythology. This aligned with McFarlane’s emphasis on detail, texture, and paint applications that could get as blood-soaked as an elevator at the Overlook Hotel. Some disfigurement one can expect from the Tortured Souls include: surgical scissors inserted into scalp (via a character named “Agonistes”), facial skin stretched back and held in place by a halo of pointy objects (“The Scythe-Meister”), small horns jutting out of the head (“Lucidique”), hooks securing a body, complete with a demonic fetus, to a metal frame via piercings in the lips and eyelids (“Talisac”), lip-less chattering teeth reminiscent of the Cenobites (“Venal Anatomica”), and, in perhaps the most creative reach, a large, jagged-toothed mouth protruding from the underside of a bound man’s belly (“Mongroid”). These gory details got people talking.1

Pearl-clutching, censorship cries, and legal concerns gushed onto the Toy Fair message board that Todd McFarlane hosted on his own company’s website.2 Of course, at a 2001 Toy Fair Q&A, McFarlane couldn’t help but push back on criticism via the fairly tired complaint that “…we live in a world that sometimes tries to be a little more politically correct than it should be…,” as reported at the time by Joe Mauceri, the panel’s moderator, on fearsmag.com. This isn’t to suggest that envelope-pushing playthings should be “banned,” just that there has to be a way to produce them without the sophomoric, edgelord attempt at the invalidation of sensitivity. Instead, one might pivot the conversation, with care for those who need to disengage, toward the ways in which art has traditionally been impalatable to some of its era, but has later been seen as a fairly accurate representation of once-prominent cultural fears, such as in the work of Heironymous Bosch, whose graphic 15th & 16th Century depictions of hell had to mostly wait for 20th Century scholars to articulate their importance as a reflection of the religious evil that threatened believers 500 years prior.

In fact, Clive Barker explicitly compared the Tortured Souls to the aforementioned artist when he said, “…this is like the first time Hieronymous Bosch might have designed a toy…” in a July 2001 newtimesla.com interview. While accurate, this works best if one overlays the jet black darkness of H.R. Giger atop Bosch’s underworld. Thus, Barker viewed his work as part of a much larger conversation, as proven even more poignantly by Tortured Souls’ most innovative feature.

II.

They bleed.

Bosch. Giger. Milton. They bleed into the narrative of Tortured Souls as supplied by its build-a-book accessory, a pamphlet-style chapter that comes with each figure. Every story explains the background, main setting (Primordium, the ancient city all Tortured Souls inhabit), and formative (largely violent) experiences of the character purchased, with cameo appearances by some of the other figures in the line. When you collect all six toys, and therefore all six chapters, you can assemble a Clive Barker novella only obtainable through completing the wave.3 Toy collecting magazine ToyFare hyped this in its October 2001 issue by describing these chapters as the stories “behind those sick-ass characters in McFarlane’s Clive Barker line.” No matter how one defines “sick-ass,” if that’s what the figures are, the novella chapters are moreso.

They’re bloodbaths, but they can also easily be read as little more than elaborate, gruesome character file cards like the (G-rated) ones that could be cut out of cardbacks attached to many 1980s and ‘90s action figures. They aren’t exactly well-written. Some choice cuts from “The Assassin Transformed,” the second chapter, which accompanies The Scythe-Meister: “Lucidique smiled. ‘You make such pretty love-talk,’ she said. ‘I mean it.”, “She circled Kreiger, as he stood amongst the blood and innards of her father”, and “The rumours quietened down a little in the city, but there was still an undercurrent, subtle but pervasive: Primordium was in a very volatile state; like an explosive, which might be set off with a jolt.” There is no subtext. No nuance. Nothing is left to the imagination. But, like the “undercurrent, subtle but pervasive,” there is something going on beneath all of this.

Clive Barker knows his craft. In addition to citing Bosch, he indirectly references the John Milton drama “Samson Agonistes” through his character, the first in the line, named Agonistes. Milton’s Samson, imprisoned post haircut, was blinded. Similarly, the McFarlane/Barker toy lacks discernible eyes, with that area of his face further covered by a ring of knives, all on the verge of cranial insertion. Both have unique relationships with God: the former being a Nazirite until he violates the code, the latter a demonic creation made by God who channels heavenly ecstasy into those he mutilates. Both are responsible for bloodshed. This isn’t to suggest that Tortured Souls consistently interweaves literary and religious references into its tales, only that Barker takes steps to directly link his dungeon of toyetic terror to centuries of artistic nightmares, thereby demonstrating the action figure as an art form capable of carrying forth that legacy.

This complexifies the paratextual relationship between toy and text. Barker conjures a text; the McFarlane figures, as paratexts, transmit that narrative to readers.4 While toys like Transformers, G.I. Joe, and My Little Pony do this, too, they primarily commune with the source narratives of parent media companies where stories might coincidentally access ancient storytelling tropes, generally without spotlighting them. Therefore, the clearest narrative chain in those cases moves from a production company like Hasbro to the toys and comics meant to contain their stories. For Tortured Souls, these chapters intentionally remix antiquity, obviously nodding to Rome, Troy, Jerusalem as well as the modern work of the aforementioned Bosch, Giger, and Barker himself. This creates a much longer and more intricate sequence of readable artistic components. In other words, these action figures contain not just their own story, but clear representations of many horror-relevant stories.

With that much textual sophistication, one might wonder what happens to play in all of this. They are still toys, after all. In cases where narrative gaps exist more readily, play does an excellent job of filling the holes. However, the entire point of these toys is hyperreal specificity. Skin has life-like wrinkles. Outfits are made up of richly textured leathery gothwear. And, on top of that, each story clearly spells out every amputation and disembowelment wrought by its protagonist. What role can play have in the realm of such precise horror figures? For me, an urgent one.

III.

They bleed.

That was the point. Mashing action figures together. Slamming hammers onto Hot Wheels until they looked like a Monster Truck’s dinner. Ripping limbs off of dolls. Tearing holes in plushies. The toys themselves were wholesome, but play bloodied them.

When I was a kid, perfection was the goal. Perfection meant no mistakes. No mistakes meant I didn’t get in trouble. No mistakes meant approval. No mistakes meant I could feel worthy of love.

For me, “perfection” was one of those goals like “immortality,” where you’ve failed just by setting your sights on it. I caught onto that early, and failed a lot, knowing the hopelessness of the mission.

There were areas where perfection felt more possible, but of little interest. Math homework, for example. I could complete it “perfectly” after many tear-filled attempts propped up by yells and threats at home. Essentially, I could eventually get the answers right, sometimes after enough takes to make Stanley Kubrick weep. But the more empirical possibilities for success were overshadowed by fears of the vaguer trials I knew I’d eventually have to face.

These came when matters of taste became issues of concrete “right” and “wrong.” There is a strain of toxic masculinity, though perhaps it exists across many gendered experiences, where a man will declare something “wrong” when he simply means that he doesn’t enjoy it. This, in its most toxic form, means that, when someone likes the “wrong” thing, the man in question takes this as a personal attack. It isn’t, in his mind, that the other person happens to have different tastes; it’s that they’ve done the wrong thing, and therefore must be shamed. The idea of a spectrum of options is very threatening to toxic masculinity, mainly because toxicity relies on rigid criteria.

Many of us, myself included, grew up with fathers who practiced this. Especially frustrating is the fact that we were never told what was on the “wrong” list, so we could only find out post-trespass, when we happened to like something that was on it. (Or, conversely, when we didn’t like something on their “right” list.) The most immediate result, in too many cases, is ridicule and abuse. But more than that, there is an invalidation that happens in these moments. You’re not “you” anymore. You’re a paternal “mini me” that you never asked to be.

Horror movies, and by extension horror toys, were on my childhood “wrong” list. To be clear, the “wrong” list isn’t the “sensible restriction” list. The “sensible restriction” list would say, “Maybe a 10-year-old shouldn’t watch Hellraiser and play with toys marked ‘For Ages 17 and Up.’” That’s, well, sensible. The “wrong” list doesn’t just restrict; it preaches that anyone, of any age, who would indulge in such filth is some incarnation of evil. As a result, you don’t wind up looking at horror movies understanding that they’re simply not appropriate for some groups, but that they are to be feared, unquestionably, forever. The former produces childhood eye-rolls. The latter, anxiety.

I remember strolling through EB Games5 in West Town Mall by myself, when I was just old enough to do that. Tortured Souls figures were there. I couldn’t even bring myself to look at them. It wasn’t that I was too scared to view the toys, but that I was afraid to become the sort of person who would. I didn’t know it then, but the first decade of my life involved others constructing for me the types of “wrong” I’d be disowned for embracing. Horror was one, yes, but the list, as I learned it, also included queerness, atheism, pot smoking, and fatness, among others. As an adult, it seems so silly to believe in a “wrong” list like that.

As a child, it was gospel, etched by God into the build-a-book chapters that developed, year after year, into a tome that made my fears existential. I turned away from the Tortured Souls, went back to my room, shut the door, locked it, and, when I was sure no one could hear, whispered to life a Fight Club using my “right” list Batman figures, kitty plushies, and never-built model kits. Destruction reigned, mistakes were bliss, and horror soaked the carpet, though I could not then tell you why.

IV.

They bleed.

Certain cancers, and their treatment, can produce blood in the stool. My grandmother endured this in her final months of life. Combined with a health care system that devalues women, immigrants, and the concerns of patients, the horror would be unimaginable if I hadn’t witnessed it personally. Her cancer ultimately spread to her stomach and gastrointestinal tract, causing the aforementioned symptom, before its advance was halted by pyrrhic victory.

Craig Windrix had this cancer, too. In 2014, he passed away from its complications. This is publicly known because, posthumously, Craig became an action figure. He now lives on as “Sgt. Craig Windrix” of NECA’s Aliens line. He’s an honorary Marine in the famous sci-fi franchise, if only in plastic. This was all made possible by his brother, Kyle, an action figure sculptor who, before working at NECA where he sculpted his brother, worked for McFarlane.

It was Kyle who sculpted the Tortured Souls figure “Venal Anatomica,” according to Jeff Saylor of figures.com.6 According to Clive Barker’s accompanying novella chapter, Venal Anatomica became a creature similar to that of Dr. Frankenstein’s creation by the interventions of Talisac, another Tortured Soul with a knack for using technology to reconstruct humanoid forms out of once-dead tissue.7

This, too, is medical horror.

I look at Venal Anatomica’s lipless mouth, the spike through his head, and the stitches that loosely assemble his body and I think about the horrors that people like Kyle and I experience as we watch cancer destroy loved ones: the voicelessness, headaches, and feelings of barely holding it all together. Sometimes, in the darkest moments, Venal Anatomica’s version seems preferable to the relentless terror of a hidden unknown, cloaked in paperwork, medicine, bills, and procedures that we scream against to no avail.

V.

In July 2001, Toys “R” Us opened its Times Square flagship store. That same month, Tortured Souls figures hit the market, R-rated figures bringing a new brand of terror to toy store pegs.

Two months later, we awoke to a different definition of “terror.” As I write this now, in September twenty-three years later, I am acutely aware of how unhelpful details can be. Some horror does not rely on the vividness of Barker’s words or the precision of McFarlane’s sculpts. Ever since 9/11/2001, I have sought the specifics of that day with near clinical exactitude, trying to understand the day that shaped my coming-of-age, but I have only found that quest has enhanced the horror of unanswerable questions. If such particulars give others closure, I am thankful; however, for me, I have only learned the infinite modulation of tears.

To view the tragedy of 9/11 through the lens of an article about an action figure line would be, I feel, disrespectful. That’s not what I want. I include mention of it solely to meditate on the ways horror becomes relative. It also reminds me that, in the years since 2001, I have not had to seek out horror in the way I looked at and for Tortured Souls action figures. Now, algorithms are eager to funnel more and more of humanity’s worst right onto screens ranging from wall- to pocket-sized. I can no longer look for one horror without receiving every horror. I do not know if we fully yet understand the ways this may have numbed a generation.

Part of me wishes the worst we could conjure is a bloodied, leather-clad toy tucked away just down-aisle of a Furby. How quaint it is that the height of Todd McFarlane’s “political correctness” complaint is an objection to an exposed plastic brain. Were that the depth of my despair, I, too, would put posts to that effect on my website out of a sense of relief that matters aren’t worse. Because of course they are worse. Our demons often spew their bile in places we want to be safe from them—churches, government buildings, family dinners8—not toy stores.

In fact, in the months after September 11th, that Times Square Toys “R” Us became something of a sanctuary for me. It grounded me in my hobby, reminded me that there are aspects of the world I do recognize, and retaught me how to play. It was there that I pushed back against the “wrong” list for the first time in my life, venturing not just toward the trembling pegs of the Tortured Souls, but into the also-forbidden pink palace of Barbie. Toys like these, disparate in almost every way, dissolved the pages of the rulebook whose sentences tied me to its caveats like restraints.

Now, I see that each plaything contained a Build-a-Figure piece whose fully constructed toy I didn’t have the strength to recognize at the time: me.

But of course, once upon a time, the Tortured Souls were scary. We made them scary. We’ve made a lot of things scary. We made the paintings of Bosch scary. We made Giger’s aliens scary. We made entire groups of people scary.

Did we do that so we wouldn’t have to process the real horrors underneath it all? Those which defy specificity? The nebulousness of death. The microscopic rampage of cancer. The hauntingly large specter of terror, its causes, and its effects. The unseeable force within that moves us toward hate.

You can’t make action figures of those.

VI.

They breathe

Life

Into toys and words alike

Because we are in many ways doing the same thing when playing with words and playing with toys. That isn’t to minimize the horrific potential of either. Both are certainly capable of containing our tortured souls.

But I think, when we imbue through play breaths of joy into our little objects, they also contain our ghosts. I don’t mean the jump-scares of writers like Barker. I mean the whisps of our pasts, no more alarming than the yellowing picture of my grandmother that sits above my kitchen table. And I think, when we play in this way, those ghosts cheer for us.

When we use words—and toys—to comfort, love, come out, sit with, feel, think, appreciate, and consider, suddenly we see the text without its paratext. Some might even say there’s something larger than ourselves happening there, in the falling away of the physical scaffolding we’ve built in order to hold our feelings.

Words and toys are among the few things you can, like Agonistes’ scissor-filled skull, crack open and keep whole at the same time. What follows is not blood or breath, but bliss. We now only have to be brave enough to play.

- And buying. The price for these figures, once they came out, shot up on the secondary market, such that one today could still easily cost a collector fifty bucks mint-in-package.

- Due to the lack of preservation, and the Wayback Machine’s inability to fully capture older, Flash-based websites, this information comes second-hand, via clivebarker.info, which has excerpted a great deal of reporting around this line from the time. Were these message board posts civil? Analytical? Wildly hyperbolic? Based on my experience on the Internet, I have an assumption, but I don’t claim to know.

- It’s important to note that this build-a-book concept emerged, here, at roughly the same time many other action figures were using the “Build-a-Figure” gimmick, in which one could build an additional toy with pieces included with every character in a line. Toy Biz (and later Hasbro) would do this most notably with their Marvel Legends figures.

- The term “paratext,” used in this way, is best summed up by French literary theorist Gérard Genette in his book Paratexts, which essentially establishes the paratext as any convention that allows a text to be received by a reader, i.e. book binding, book jackets, forewords, etc… Media scholars Jonathan Gray and Henry Jenkins moved this forward to discuss how pop culture brings even more items, like toys, to this list.

- Gamestop, now.

- Kyle may have sculpted others in the line, too, but this was the one I could verify through a December 4, 2002 article.

- Agonistes, referenced earlier, does something similar, but he uses the force of God in his surgeries.

- In Primordium, as Barker writes in a number of the Tortured Souls novella chapters, and beyond.

This was an absolutely beautiful and haunting piece. Thank you so much for writing it and sharing it.

Thank you so much for reading!