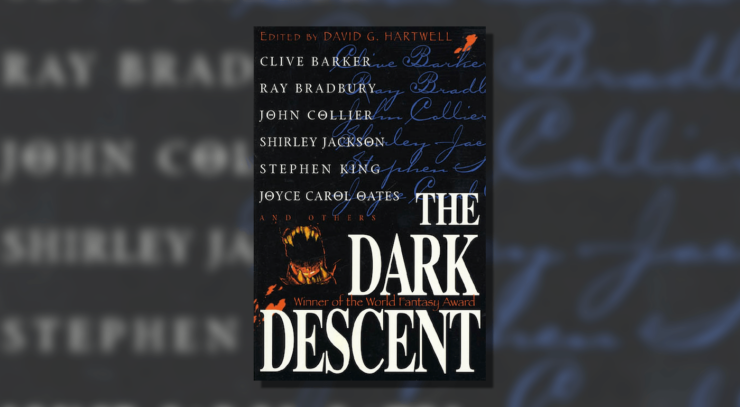

Welcome back to Dissecting The Dark Descent, where we lovingly delve into the guts of David Hartwell’s seminal 1987 anthology story by story, and in the process, explore the underpinnings of a genre we all love. For an in-depth introduction, here’s the intro post.

In what’s becoming an odd theme in The Dark Descent, we’ve had multiple stories by Lovecraft, multiple stories by King, and now in “Crouch End,” we find the unholy union of the two: King doing Lovecraft. It’s a synthesis of Hartwell’s earlier commentary, with Lovecraft being one of the most influential writers in horror of the early 20th century, and King being easily one of the most successful horror writers of the late 20th century and ushering in the horror boom of the ’70s and ’80s. “Crouch End” works harder than one would expect for a Lovecraft pastiche. Its foundation might be Lovecraft (or possibly Campbell), but (as we outlined in “Breaking an Ancestral Curse”) its preoccupations are all King, from the familiar “guys sitting around and talking about strange events” frame to the way it uses King’s empathy and understanding of emotion to explore grief and trauma. In its terrifying and hallucinatory spiral, “Crouch End” elevates the Lovecraft Mythos by giving its nameless horrors emotional stakes and a genuine air of menace that few writers outside 1970s-era Stephen King could provide, a modern portrait of how things can go with one simple turn of bad luck.

In the sleepy London suburb of Crouch End, a hysterical American woman named Doris Freeman rushes into the police department with a terrifying story of her missing husband Lonnie, a strange cab ride, a sinister cat, and a nighttime detour through an alternate version of Crouch End neighborhood populated by monsters and unusual inhabitants. While the policemen (particularly the younger PC Farnham) are incredulous, something rings unnervingly true about Doris’ story to the elderly PC Vetter—something related to several unusual open cases in his “back file.” By the end of the night, one more person will be missing, and all will be forever marked by the Freemans’ excursion to Crouch End.

As with most modern existential horror, all the story requires is a single bad moment to suddenly unleash the chaos roiling behind the world. The second the Americans get into the cab that takes them to the alternate Crouch End, their fate is sealed. From there, King’s story is a masterful plunge into the depths of horror, beginning with an odd headline reporting “SIXTY LOST IN UNDERGROUND HORROR” and a brief glimpse of rat-headed delinquents, before gradually sliding into deeper and more surreal territory with every step. It’s a gradual decline, one slow enough that it can easily be dismissed early on, only to come back nastier, more surreal, and much more dangerous each time. The inciting incident being a single, seemingly random bad moment is an important distinction, too, between Lovecraft and King—Lovecraft’s protagonists tend to be curious souls who seek out knowledge only to be confronted with unnamable horrors as a result.

There’s safety and distance in a Lovecraft protagonist’s eventual madness, knowing that they sought it out. All you must do is avoid going in the scary house or reading the wrong book, which is why Lovecraft’s cosmic horror occupies Hartwell’s “moral-allegorical” and “psychological” strains and not his third category, which deals with the fantastic, absurd, and surreal. Modern horror refutes that barrier of safety as King does here—the Freemans have done nothing to deserve or invite their fates. In most stories, they’d be safe but as with many modern cosmic horror stories, they simply stumbled upon a point where (in the words of Vetter) “the world is a bit thinner” and fell face-first into Crouch End Towen, an alternate version of Crouch End serving as a feeding ground for the “underground horror” living in that thin point. The Freemans’ only crime was taking the wrong cab, a thing that could happen to literally anyone.

King’s influence also extends into the empathy we feel for the horrible situation the Freemans find themselves in. King’s strength has always been crafting characters that make you care what happens to them, whether for good or ill, and the Freemans continue the trend by acting like, well, rational people. At first, the odd touches of Crouch End can be explained away as momentary tricks of the light or odd turns of phrase—after all, the couple are already in an unfamiliar space and lost in a neighborhood they barely know, looking for a colleague Lonnie Freeman’s barely met. Even after the sudden and mysterious disappearance of the cab and its (in retrospect) mildly unnerving cabbie, the Freemans gamely travel on, trying to find an address they should easily have been able to walk to.

The more normal they try to pretend their situation is, the more sinister it gets, starting with deformed children and escalating to their sinister encounter with the man-shaped hole in the ground where something gets hold of Lonnie. Lonnie’s eventual aging and decay in front of Doris’ eyes is similarly a fear that’s grounded in reality—watching the person you love grow old and die in front of you while you can do nothing to stop it. In fact, it seems to be Doris’ thoughts and fears Crouch End feeds upon—the “underground horror” appears only after she reads the signboard, the increasingly sinister cat that stalks them through the suburb is first seen in the window of the curry shop when the cab strands her in Crouch End, and the more grounded if sinister elements are common fears tourists experience, like being lost in an unfamiliar place and having encounters with sinister locals.

By the end of the story, Doris is further tormented by her husband aging and decaying before her eyes just as he gets pulled into the shadows and messily eaten by what looks like a giant version of the stray cat. There’s a sense that Crouch End itself is wrong, not that it’s a place for any kind of nameless god, but that the area itself feeds on the unwary…and mercilessly enjoys playing with its food. It’s similar to Ramsey Campbell’s milieu, where local (and terrible) customs and spirits terrorize newcomers who unwittingly stumble into their clutches, which jibes well with the idea of King’s modern take on Lovecraft. The final moments of the tale are, however, all King’s own—while Lovecraft might have stopped with Doris’ escape, King continues four years into the future to show how the two disappearances that one summer night affected everyone involved. Trauma, especially long-term trauma, leaves scars.

King is fantastic at showing the horror that bearing those scars entails. It’s an emotion and focus not seen in Lovecraft, and the story ends on a disquieting note, even if some of the characters have managed to move on. “Crouch End” is about that grief, trauma, and how the scars never truly fade, fusing Lovecraft’s hostile universe and hallucinatory visuals with King’s gift for empathy and understanding to underscore a growing sense of menace and unsettlement. It’s this fusion of elements and the introduction of ones just outside the normal Lovecraftian mythos that makes “Crouch End” a disquieting and horrifying elevation of Lovecraft’s themes with a voice and sensibility all King’s own, paying tribute to Lovecraft’s Mythos while maintaining its own distinct tone and persona.

And now to turn it over to you: Did King do enough to differentiate himself from Lovecraft while drawing on his work? How much of Doris Freeman’s experience was with a Silent Hill-esque genus loci? And what’s the best depiction of trauma in cosmic horror you’ve read?

Please join us in two weeks for infamous Twitter poster and gothic horror historian Joyce Carol Oates and “Night-Side.”

The cat was a VILLAIN?!? Truly, truly this story is a shameless and appalling betrayal of H. P. Lovecraft’s creative vision, no matter how well-written! (-;

In all seriousness, it’s amusing to wonder what a letter from H.P. Lovecraft to Mr Stephen King would look like (Heck, an exchange of letters between the two might be an excellent hook for a short story told in epistolary form): I believe the late Mr Lovecraft kept up a correspondence with quite a number of fellow scribes in the weird tales genre.

That’d be a hell of a thing, a series of letters between a blue collar “aw heck aw shucks” guy and the most arch and dramatic man on the planet.

I think they’d talk mainly about cats and dogs, to be honest. For all the cats are also rough customers in King, “General” and the intensely depressing parts of Pet Sematary make me think he likes cats, he just likes dogs more.

Two things I would give to HPL…a few episodes of Star Trek, so it might change his outlook—and a copy of 1982’s THE THING.

Is the horror existential? Maybe, but in a more personal way than Lovecraft. The second disappearance, PC Farnham, makes me think that Crouch End not only feeds on the unwary but actively lures them in. So the older constable, Vetter, survives, because he understands how to negotiate the dangerous terrain, but the ones who do not see the dangers are, as King puts it, together again, as folders in the ‘back files’ of unsolved cases.

Oh, no, definitely existential. The idea of being constantly under threat like this precedes similar works by Barker and Ligotti.

I don’t think the Towen lures people to it, because that would defeat the overarching feeling of the piece: That the universe is thin at points and when people fall through, horrible things happen to them. That requires a creature that doesn’t care enough to lure prey. It’s also a call-forward to (and I wish I had more space and time to get into this in the piece) From A Buick 8, where a similar “thin place” is anchored to a strange car in a state trooper garage. King’s more Lovecraftian creations aren’t actively malicious, they just do things that are horribly damaging to humans (for example the thing that replaces the Turtle in It).

The things that are malicious enough to seek out victims are of a lesser order: Ardelia Lortz, Pennywise, Flagg, the Little Doctors…these are all things that can be defeated. If we look at King’s greater world alongside “Crouch End,” the truly weird and eldritch creatures are often the ones that kind of just shrug their shoulders and keep moving indifferent of the horrors they leave in their wake, undefeated and unscathed by the attempts of humans to fight them if they even notice at all.

But that begs an interesting question: With things like the transitional forms, like the way the room in “1408” is between the Deadlights and Crouch End, is it malicious enough to know what it’s doing, or does it just have an effect on the unwary who stumble into its stomach for digestion?

I occasionally find other King works where aware characters do navigate the ‘thinness’ successfully, as in “Mrs. Todd’s Shortcut”. And some of the cosmic Lovecraftean critters do seem more actively malicious, such as in “The Mist”. But King’s universe is a broad one, so I am sure we can locate those entities like Room 1408 or the Overlook from The Shining, where their sentience is just below the surface of human awareness but sometimes bubbles up and over.

Or maybe Mr. King just had a trauma with hotels.

With the Overlook, what gets me is that essentially it built up so many ghosts it became an entity via bootstrapping itself. I keep flashing back to that one scene in Doctor Sleep with the room full of tackleboxes as Danny’s tried to take the hotel apart piece by piece over years and he’s nowhere near done by the end of that book. It is the wasp’s nest.

There was a short

Film of this made for an anthology series. Somewhat hard to find but it’s on YouTube. Some bad CGI but has moments that are quite good.