Welcome back to the Short Fiction Spotlight, a weekly column co-curated by myself and the most excellent Lee Mandelo, and dedicated to doing exactly what it says in the header: shining a light on the some of the best and most relevant fiction of the aforementioned form.

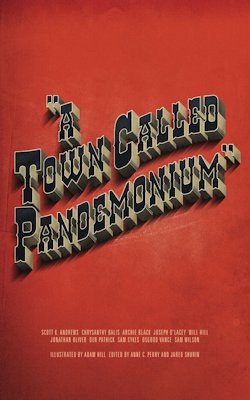

Today, to whet our appetites for Jurassic London’s newly-announced next project, The Lowest Heaven, we’ll be taking the tuppenny tour of a town called Pandemonium—a fierce frontier full of silver dollars and rusty revolvers—by way of a pair of tales from the superb shared world anthology of the same name, which sees an army of rising stars collaborate on one deeply weird and wonderfully wild west.

We begin, as does the luxurious hardcover edition of A Town Called Pandemonium, with a violent tragedy from the author of the bloodless Department 19 novels: a standard “The Sad Tale of the Deakins Boys” by Will Hill departs from fantastically.

Once upon a time, the Deakins boys had a family. You wouldn’t be caught calling it happy, but it existed—there was that—and they all liked life alright.

That was then. This is now:

After their mother had succumbed to the fever the previous winter, Amos had needed a new target for the bitter rage that boiled endlessly inside him, and Isaac had been the obvious choice; he lacked Nathaniel’s strength and propensity for violence, and Joshua’s almost uncanny ability to make the decisions that kept their hard-scrabbling family going. Isaac had read too much, and fought too little; as far as his father and his oldest brother were concerned he was a shirker, and wet. But in the end Isaac had surprised them all with a streak of boldness that had never been previously hinted at.

Of a morning a couple of months ago, Isaac upped sticks and abandoned his brothers to live and work in the mean streets of Pandemonium as an enforcer for Rep Calhoun, who runs the whole sorry show. That left Nathaniel and Joshua to care for raving Amos in a shack atop Calhoun’s Peak, near to the supposed seams of silver the Deakins dream of making their fortune from.

Alas, the boys have been plum out of luck ever since Amos gambled their greatest claims away in a fit of idiocy… but despite everything, they have hope—for a better tomorrow, or at least a reasonably decent today—so when Joshua gets a gut feeling about one spot on an otherwise unremarkable wall of rock, they set a stick of dynamite alight and pray for the future.

Their wish is Will Hill’s command. The blast reveals a cave covered with strange paintings, but the brothers have little time for ancient history when they realise they’ve stumbled upon a seam of silver so deep that it could see them through the rest of their lives in the lap of luxury. They set to excavating it immediately, ever aware that there’s a storm coming:

The storm was going to be big, the first true monster of the summer, and it seemed in no hurry to make its way across the plains towards Calhoun’s Peak. It was as if it knew full well that the Deakins men and the few hundred souls who lived in the fading, bedraggled town that huddled at the mountain’s base, had nowhere to go, and nowhere to hide. It would come at its own slow speed, implacable as death.

Meanwhile, in Pandemonium proper, Isaac has been asked to speak with saloonkeeper Sal Carstairs, who has taken out his frustration on the saloon’s staff ever since his wife vanished one morning “without excuse or explanation […] along with every single dollar she had deposited in the town’s bank and every single cent that had been in the Silver Dollar’s safe.” Recently, he beat one of his girls within an inch of her life in front of everyone, and Isaac’s employer believes that a message must be sent—in the physical sense if necessary.

Truth be told, these two stories only come together during the gruesome conclusion of “The Sad Tale of the Deakins Boys.” Otherwise, Isaac’s section seems of secondary interest at best. What it does do, I should stress, is set out the shared world of A Town Called Pandemonium so that the other authors involved in this tremendous collection—including Sam Sykes, whose contribution we’ll be talking about next—can get right to the thick of it when their number’s up.

It’s worthy work, overall, but devoid of that context, I’m afraid it does rather overburden aspects of this individual narrative. “The Sad Tale of the Deakins Boys” would have been a more satisfying narrative if instead of said, Will Hill had channelled his creative energies into character development—especially as regards Amos, given how pivotal his actions (or indeed inactions) prove.

On the whole, though, these caveats do not detract from the cumulative force of this chilling short story. Hill gets a lot of mileage out of the crawling onset of horror: an indescribably disturbing development I confess I was not expecting here at the very outset of the Café de Paris edition of A Town Called Pandemonium, before I knew which way was up and what was what.

I won’t spoil the specifics… except to say that the boys should maybe have paid more attention to those cave paintings.

“The Sad Tale of the Deakins Boys” might not be the strongest story in A Town Called Pandemonium, yet it is, I think, of the utmost importance. Worldbuilding, at worst, can be abysmal busywork, and given how much of it Will Hill does herein—and what a boon it is for the later tales—I’d consider this short a success if it was even slightly worthwhile in its own right. But mark my words when I say it’s so much more than that. “The Sad Tale of the Deakins Boys” may be slow to get going, but I have not felt such perfect dread as I did by the end in recent memory.

Whilst Will Hill takes his time establishing a rapport with the reader, very deliberately building that sense of dread via the aforementioned storm and other such plot points, in “Wish for a Gun,” Sam Sykes demands attention from the first. But of course he does! The man’s quite a character.

Quite an author, also, on the basis of this short story alone… which is not to say that his ongoing fantasy saga is lacking—on the contrary, The Aeons’ Gate began with a bang, and it’s gotten bigger and better with each subsequent book. Here, however, freed from the need to make everything barbed and elaborate and unimaginably massive, Sykes is able to zero in on several understated ideas and explore them in a more emotionally satisfying fashion.

His use of the first person perspective, for instance, is immediately arresting. Syntactically problematic, but let’s not be pedantic, because “Wish for a Gun” is massively impactful from word one:

Was a time when I knew the earth.

Was a time when I knew what made the green things grow from her. Was a time when I let it drink in drought while my family and I went thirsty. Was a time when I would build my house next to my daddy’s on this earth and even when he was called back to heaven, I’d still have the earth under my feet.

Some men had guns. Some men had God. I didn’t need those. I didn’t need nothing but the earth.

Back when I thought I knew it.

But Matthias doesn’t know the earth no more. Fact is, he doesn’t know much of anything at the inception of this harrowing narrative, because he’s suffered an awful loss: namely his wife, and with her, his way of life. To wit, our man is in a bedraggled daze for the fiction’s first few sequences, desperately trying to get the measure of how to go on now that Iris is gone.

Then a dead girl climbs out of a well and gives Matthias a gun. Swears blind that she’ll bring Iris back to boot if he can bring himself to kill with it.

And just like that, he has a purpose:

That big hole of nothing. I got a name for it, now.

Earth. Or lack of it.

You shove a man off a cliff, he takes a moment to scream to God and ask why. The next moment, he grabs a clump of earth and holds on. He’ll stay there for an eternity, feet dangling over nothing, sharp rocks beneath him, holding onto a root or a rock or dirt and thank God he’s got that earth.

And in that moment when his fingers slip and he’s not quite screaming but he ain’t holding on anymore, that’s the big whole of nothing. When something is close, but you can’t touch it anymore. When everything else is so far away, but you can’t go back.

Man needs something to hold onto.

In two weeks, I learned how to hold onto the gun.

“Wish for a Gun” is an inspired short story about loss, and learning to live with it. It’s hardly half as long as “The Sad Tale of the Deakins Boys,” yet it packs at least as much of a punch, thanks in no small part to Sykes’ characteristic confidence. Brought to bear on this tale’s daring narration, his extraordinary poise makes something that would seem flashy in less steadfast hands feel… practically natural.

In my heart of hearts, I understand why more authors don’t try this sort of thing, but “Wish for a Gun” made me wish more of them had the nerve to attempt similarly ambitious endeavours. It doesn’t feed into the larger narrative of A Town Called Pandemonium in quite the critical way Will Hill’s story did, but “Wish for a Gun” is richer, and truer too, for our understanding of the world around it—an understanding arrived at care of a certain sad tale.

So there we have it. Two splendid short stories from a pair of authors taking distinctly different tacks than they have in the past. And this is just the beginning of A Town Called Pandemonium—quite literally in the expanded Café de Paris edition, which I see is almost sold out.

Do yourself a favour, folks: grab a copy while you can.

And hey, if you’re late to the party, there’s always the Silver Dollar digital edition. It’s almost as awesome.

Niall Alexander is an erstwhile English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com, where he contributes a weekly column concerned with news and new releases in the UK called the British Genre Fiction Focus, and co-curates the Short Fiction Spotlight. On rare occasion he’s been seen to tweet about books, too!