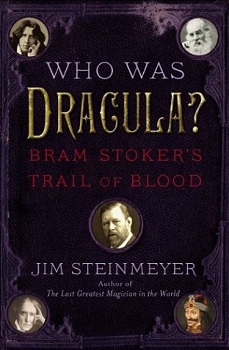

Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula has inspired countless iterations, inspirations, and parodies of vampires. Particularly in the last decade and a half, vampires have dominated pop culture. Some glower, some glitter, some brood, some have uncontrollable bloodlust, some are gorgeous, some grotesque, but all take most of their mythology and supernatural “rules” from a standalone novel written by a mild-mannered, put-upon Victorian Dubliner. Jim Steinmeyer’s Who Was Dracula?: Bram Stoker’s Trail of Blood looks at Stoker’s autobiographical reminiscences and personal and professional cohorts to determine just who exerted the greatest influence on the creation of the novel and it’s iconoclastic villain.

Dracula by Bram Stoker was the second adult book I ever read. The first was Jurassic Park by Michael Crichton, which scared the pants off me. It probably didn’t help that my mom insisted 9 years old was too young for such a book, and because I’m impulsive and mildly reckless I immediately stole it off her bookshelf and read under my sheets in the middle of the night. For months afterward I was convinced I’d be eaten by a Tyrannosaurus Rex at the top of my stairs. I was bolder and braver at 12 when I picked up Dracula. I don’t recall what intrigued me. Vampires weren’t on TV in the mid 1990s, and I was too unobservant to encounter Lost Boys or Interview with a Vampire in any influential context. What I do remember is someone at the local Waldenbooks created a Classics section and Stoker was front and center, and, for whatever reason, I had to have it.

I didn’t read Dracula like a normal person. I grew up surrounded by a very restrictive religion, and was already rebelling against it in subtle ways by the time a hundred year old book about vampires, lust, and death fell into my lap. So I did what any envelope-pushing tween would do: I read Dracula in church. Only in church. With 40 minutes every Saturday, pausing only for prayers, hymns, communion, and every time my mom shot me irritated looks, it took me the better part of a year to complete. I think I enjoyed the recalcitrance more than the book itself (once I got my driver’s license I routinely showed up at church in 8 inch platform hooker boots and blaring “Closer” by Nine Inch Nails), but my choice in literature later proved formative. After Dracula I quickly consumed the Classics like the were going out of business. Shelley, Stevenson, Eliot, Dickens, Shakespeare, Wilde, Verne, Twain, author and subject didn’t matter, though I did tend to navigate to the darker, more frightening, supernatural/paranormal/science fiction-y books. Then I discovered Garland, Salinger, Bukowski, and Houellebecq, and my reading tastes took a sharp left turn. It took many difficult years, comics, Neil Gaiman, and Doctor Who to get me back on the SFF track.

I tell you all this not as an introduction to my autobiography but because I want to impress upon you how important Dracula was to me, even if I didn’t realize it at the time. I rarely read non-fiction now, and I haven’t touched Dracula since my days trying to figure out how to keep reading while pretending to sing hymns. So I was both eager and reticent to review Steinmeyer’s Who Was Dracula? Fortunately, it proved better than expected.

Who Was Dracula isn’t a straightforward biography of Stoker. There is a great deal of biographical information, but it’s doled out non-linearly and in context of the different people and circumstances that may have influenced his most famous creation. Steinmeyer doesn’t aim to be Sarah Vowell or Bill Bryson, and there’s no sarcastic humor or personal discoveries. He has written a studious and serious—yet not dry or stuffy—book about Dracula the book and Dracula the character. Stoker’s professional position placed him in the upper echelons of London society. While not a celebrity himself (his novels were never wild successes in his lifetime, but Dracula was by far the most well-received), he did associate with late 19th century London’s brightest stars. Of the many famous people he encountered, Steinmeyer pulls Walt Whitman, Henry Irving, Jack the Ripper, and Oscar Wilde to prominence.

Wilde was an old family friend from Dublin, where Stoker grew up. Stoker was a star-struck fan of Whitman’s, and met him a few times while on tour with Irving. Irving was one of the most famous—and controversial—actors of his day, and Stoker was his Acting Manager (a combination of an assistant, agent, and theatre manager) and lifelong friend. As for Jack the Ripper, Stoker may have only known him through the sensationalized reports of his attacks, but if he really was notorious charlatan Francis Tumblety, then the two men might have crossed paths through their similar social circles. Steinmeyer argues that each man affected different aspects of the development of Count Dracula and Dracula: Whitman’s writing style and physical appearance, Irving’s artistically aggressive personality and his famous portrayal of Mephistopheles in Faust, Jack the Ripper’s sadistic brutality, and Wilde’s brazen and unabashed sexuality.

Beyond the intriguing look at London and its denizens in the 1890s, Who Was Dracula is fascinating in its exploration how Stoker crafted his most famous work. At times, Steinmeyer’s book feels a bit like the Cliff’s Notes version of how the book came to be, and there are some descriptions of Stoker’s behavior and reactions that seem to be based more in exaggeration or supposition than hard evidence. But Steinmeyer redeems himself with several rarely seen authorial tidbits. The most exciting for me was the translated portions of Stoker’s notes in the earliest stages of Dracula:

People on train knowing address dissuade him. Met at station. Storm. Arrive old Castle. Left in courtyard. Driver disappears. Count appears. Describe dead old man made alive. Waxen color. Dead dark eyes. What fire in them. Not human, hell fire. Stay in castle. No one but old man but no pretence of being alone. Old man in walking trance. Young man goes out. Sees girls. One tries to kiss him not on lips but throat. Old Count interferes. Rage & fury diabolical. This man belongs to me I want him. A prisoner for a time. Looks at books. English law directory. Sortes virgilianae. Central place marked with point of knife. Instructed to buy property. Requirements consecrated church on grounds. Near river.

Yep. One hundred and sixteen years later and it’s still creepy as all get out.

Jim Steinmeyer’s Who Was Dracula?: Bram Stoker’s Trail of Blood is out on April 4th from Tarcher

Alex Brown is an archivist, writer, geeknerdloserweirdo, and all-around pop culture obsessive who watches entirely too much TV. Keep up with her every move on Twitter, or get lost in the rabbit warren of ships and fandoms on her Tumblr.