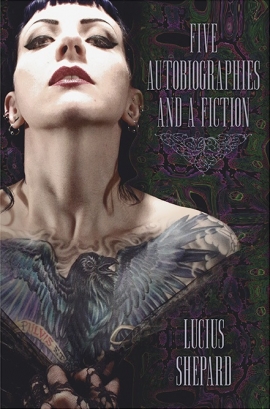

Lucius Shepard’s new collection Five Autobiographies and a Fiction is required reading for fans of the author. People who have never read anything by Shepard may love it too, but because of the specific nature of this set of stories, it’ll definitely have more impact on readers who are familiar with the author. If that’s you, I’d go as far as saying that this is nothing less than a must-read, because it will dramatically change and enrich your understanding of the author and his works.

As the title of this new collection indicates, Shepard approaches aspects of his own life and personality from five different directions. Calling these stories “autobiographies” is as meaningful as it is deceptive. “Pseudo-autobiographies” or even “meta-autobiographies” would be more appropriate, but it’s understandable why Shepard and Subterranean Press avoided those horrible mouthfuls.

First things first: Five Autobiographies and a Fiction contains, as you might expect, six stories: “Ditch Witch,” “The Flock,” “Vacancy,” “Dog-Eared Paperback of My Life,” “Halloween Town” and “Rose Street Attractors,” varying in length from short stories to full length novellas.

Before you get to the stories, however, there’s an introduction by Shepard that’s as essential as the stories themselves, because it places the entire collection in the context of the author’s life. Shepard describes his troubled adolescence in a way that’s so frank and open that reading it borders on the uncomfortable. He mentions that the genesis of this project was a realization that the two main characters in the story “The Flock” may represent “two halves of my personality that had not fully integrated during my teenage years.”

In “The Flock” and other stories in this collection, most notably the stunning “Dog-Eared Paperback of My Life,” Shepard examines his personality “from the standpoint of an essential divide, sensing perhaps that some mental health issues remain unresolved.” There are similarities between many of the protagonists, some easily identifiable as parallels with the author, others less obvious. Taken on their own and without the overarching “autobiographies” moniker, it might not have been as clear that Shepard is dissecting his own life, or at least alternate versions of his life. Seen together in the context of this collection, there’s no getting away from it.

All of this makes reading Five Autobiographies and a Fiction an odd, thrilling process. Yes, they’re instantly recognizable as Lucius Shepard stories, full of interesting twists and gorgeous prose, but there’s also something voyeuristic about the reading experience. Shepard makes it clear that these characters are potentialities, near-hits (or near-misses?), versions of himself from some parallel dimension that could have been real if his path had been slightly different.

Most of the main characters in these stories range from “annoying” to “spectacularly unpleasant.” Many of them treat women like objects and other cultures like caricatures, even when it’s clear that they have the mental and emotional capacities to step beyond this. They’re stuck in the ruts carved by their inglorious pasts. They coast along because it’s easier than reaching for something new, until they’re bumped out of their paths by some confrontation or realization.

Some examples: Cliff Coria, the main character of “Vacancy,” is a former actor turned used car salesman whose past misdeeds come back to haunt him. He self-describes as “an affable sociopath with no particular ax to grind and insufficient energy to grind it, even if he had one.” One of the main characters in “The Flock” reflects, after sleeping with his friend’s girlfriend, that “Getting involved was the easy way out. Not the easy way out of Edenburg, not out of anywhere, really: but with Dawn and a couple of squalling kids in a double-wide parked on my folks’ acreage, at least my problems would be completely defined.” The main character in “Dog-Eared Paperback of My Life” describes himself as follows: “I knew myself to be a borderline personality with sociopathic tendencies, subject to emotional and moral disconnects, yet lacking the conviction of a true sociopath.”

If you tried to make a Venn diagram of these people’s characteristics, the areas of overlap would be clear. If you’ve read Shepard before, you can probably add some examples from past stories, but in this case the stories are offered as “autobiographies,” contextualized and dissected in the introduction. Some autobiographers self-mythologize, casting their lives in a more pleasing light. Shepard is, at least indirectly, doing the opposite. I can’t say that I’ve ever experienced anything similar in fiction.

“Dog-Eared Paperback of My Life” adds another fascinating dimension to the collection by having its main character Tom Cradle (a bestselling author) come across a novel by another Tom Cradle, one who took a different path in a number of ways, including the fact that Cradle Two didn’t listen to some advice an editor gave him early in his career: “long, elliptical sentences and dense prose would be an impediment to sales (she counseled the use of “short sentences, less navel-gazing, more plot,” advice I took to heart.)” I don’t think anyone who’s read Shepard before can work through that tangle without grinning, but just to make sure, he concludes the paragraph with “It was as if he had become the writer I had chosen not to be.”

Later on in this story, the (fictional) author quotes one of his fans (who strayed in from a parallel universe) while she cuts apart postmodernist fiction, in a way that feels very much like quotes taken from real reviews. It doesn’t get much more meta than that. It’s also hilarious, especially when the author wishes the woman would turn back into her previous, hypersexual self rather than this “pretentious windbag” who’s over-analyzing his fiction. (Writing some of these quotes down as a reviewer is, by the way, a great cause for reflection.) Elsewhere in the story, Shepard/Cradle rips apart a number of SFF fan and author archetypes in a gloriously misanthropic, multi-page rant that will probably piss off as many people as it amuses.

Even though “Dog-Eared Paperback of My Life” gets a bit muddled towards the end, it’s my favorite entry in the collection because it crystallizes the ideas from the introduction and the other stories in one dark, hallucinatory Heart of Darkness-like journey. It’s a novella that deserves a full-length review in itself, but then so do most of the other rich, thought-provoking stories in Five Autobiographies and a Fiction.

The “fiction” mentioned in the book’s title refers to the final entry, “Rose Street Attractors,” a twisted ghost story set in the underbelly of Nineteenth Century London. It’s a great story, but I felt that it took away somewhat from the impact of the preceding five stories. In itself it’s perfectly fine, but there’s a sense of disconnect between it and the others. I don’t think the collection would have suffered if it had been titled “Five Autobiographies,” or (as I somehow thought before reading this book) if the title’s “fiction” had referred to the introduction, making explicit the idea expressed at its very end: “[…] it has every bit as much reality as the fiction I am living, a narrative that becomes less real second by second, receding into the past, becoming itself a creation of nostalgia and self-delusion, of poetry and gesture, of shadows and madness and desire.”

For fans of Lucius Shepard, this collection will be revelatory, but I wouldn’t call it his best work. Several of the stories follow a pattern that’s maybe a bit too obvious. Some of the endings feel too similar, some are a bit rushed. Maybe most importantly, some of these stories work mostly because of the context they’re in: without the introduction and the instant additional layer of meaning it imparts, I wouldn’t rank them with my favorite Lucius Shepard stories. Even an average story by this author is worth reading, but I’d still steer new readers to some of his previous works instead, especially last year’s collection of Griaule stories (review).

I wrote down so many quotations from Five Autobiographies and a Fiction that I might have been able to compose this review using quotes only, communicating in the way the soldier who told a story using only slogans did in Gene Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun. To conclude, let me add one more quote. This theory from “Dog-Eared Paperback of My Life” offers one possible explanation how one author can write five vastly different autobiographies: “[…] our universe and those adjoining it were interpenetrating. He likened this circumstance to countless strips of wet rice paper hung side by side in a circle and blown together by breezes that issued from every quarter of the compass, allowing even strips on opposite points of the circle to stick to each other for a moment and, in some instances, for much longer; thus, he concluded, we commonly spent portions of each day in places far stranger than we were aware.”

Five Autobiographies and a Fiction is published by Subterranean Press. It is available April 30

Stefan Raets reads and reviews science fiction and fantasy whenever he isn’t distracted by less important things like eating and sleeping. You can find him on Twitter, and his website is Far Beyond Reality.

I’ve ordered this, and am now even more excited to read it. To be honest, I know very little about him aside from his stories. But I rarely read one of his stories that doesn’t affect me in some way. He’s one of my very favorite writers.

I remember the first book I bought of his back in college, Life During Wartime. I ordered it from a small bookstore and when I went to pick it up found that everyone working at the store had passed the book around and become instant fans. After that they carried everything of his they could get their hands on, always ordering an extra copy for me (yet another reason I miss independent bookstores, including this one which closed ten years ago). His writing draws in people who’ve never before considered sf an option.