Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

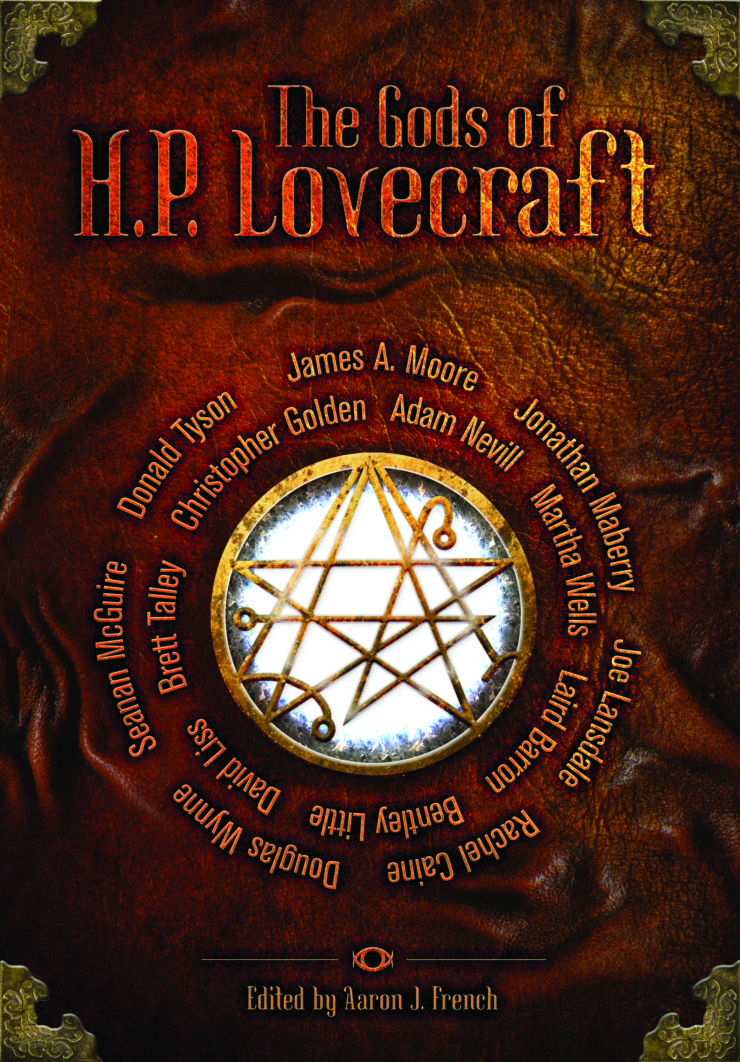

Today we’re looking at Seanan McGuire’s “Down, Deep Down, Below the Waves,” first published in Aaron J. French’s 2015 collection, The Gods of H.P. Lovecraft. Spoilers ahead.

“Jeremy plucked the white mouse from its tank as easily as he would pick an apple from a tree, grabbing the squirming, indignant rodent without hesitation or concern. The mouse squeaked once in furious indignation, no doubt calling upon whatever small, unheeded gods were responsible for the protection of laboratory animals.”

Summary

Violet Carver, graduate student in life sciences at Harvard, has four close “friends.” Terry conducts a weird plant project. Christine analyzes epigenetic data. Michael does something involving lots of maggots. Jeremy shares a lab with Violet, for their work meshes: he studies tumors in mice, and she documents social changes in the infected animals. Their relationship is symbiotic, like that of a clownfish and sea anemone. Outgoing Jeremy draws attention from retiring Violet, which allows her to work undisturbed.

And she has a lot of work to do, as she has a second, secret experiment underway. Twice a month she and her friends meet at a local pizzeria; twice a month, Violet doctors their jar of Parmesan with “a mixture of her own creation.” Parm fans, they gobble it up, while she monitors their “dosages.” Over pizza one night, Violet invites the crew to spend spring break at her parents’ bed and breakfast in sleepy seaside Innsmouth. Her grants run out at the end of the semester, and she’ll probably have to leave Harvard. Baiting her invite with emotional cheese, she lets her voice break, and her friend agree to the excursion.

Violet drives up the coast with Jeremy, who’s disgruntled that her folks expect her to waste her “brilliant, scientific mind” in a hick town. She hides long-simmering resentment at these people who marvel that someone from such a backwater isn’t a “babbling, half-naked cavegirl.” The smile she flashes Jeremy reveals teeth she lately must push back into their sockets each morning—another sign her time is running out.

Innsmouth’s quaint architecture, and the stunning view between cliffs and sea, wow Jeremy. It was founded, Violet says, in 1612, by people who wanted to follow their own traditions without interference. Carver’s Landing Inn earns another wow. It stands four stories high on a bluff over the Atlantic. Part Colonial, part Victorian, it’s the handiwork of generations and has grown as organically as a coral reef. Violet runs inside ahead of her friends to reunite with her older sister and “sea-changed” mother. Sister, who unfortunately remains mostly human, greets the guests as Mrs. Carver. Two youngish brothers are also presentable enough to appear, while the rest of the family peers from behind curtains.

Violet shows Terry her room. Maybe they’ll go on a boat trip to Devil Reef, which was “accidentally” bombed by the Feds in 1928. Now it’s overrun with scientists bent on conservation. Occasionally one dives too deep, so sad, but that reminds colleagues to respect the sea. Terry’s excitement makes Violet feel a little guilty, but hey, those mice never volunteered for experimentation either.

At dinner, sedatives in the fish chowder knock out the guests. Mother emerges, hideous and beautiful in her transition. Does her “arrogant, risk-taking girl” really think this plan will work? Eldest brother, needle-toothed, expresses doubt as well. Violet counters that Dagon chose her for a reason. She’ll make Him proud, or she’ll answer to Him when she goes beneath the waves.

The four friend-subjects are chained to beds upstairs, hooked up to IVs that drip Violet’s purified plasma and certain biogenic chemicals into their veins. It’s a still more powerful “change agent” than the doctored Parm she’s fed them for months. Two subjects have Innsmouth blood in their family trees; two don’t. Violet has submitted to the humans’ great god of Science to learn how to quicken Dagon’s seed and return His more genetically-dilute children to the sea, but she never planned to go human enough to feel sorry for her lab “rats.” The two controls will probably die, she fears. But if the two with Innsmouth blood transition, that could save slow-changers like her sister decades of “land-locked” banishment.

When half the life science department doesn’t return to Harvard, authorities visit Carver Landing. Sister tells them everyone left days ago, planning to drive to Boston along the coast. Eventually searchers pull the missing students’ cars from the ocean, empty of occupants. Those occupants lie upstairs at the Inn, losing hair and teeth, bones softening, eyes developing nictitating membranes and coppery casts. Christine dies, unable to undergo a change so alien to her pure human genetics. She still tastes human, too, when the Carvers dispose of her body according to traditional methods, which include feeding spoonfuls of her to the survivors. Michael looks to follow Christine, but Terry and Jeremy, the subjects with Innsmouth blood, may prove Violet’s procedure viable.

One morning Jeremy manages to break free. He clubs Violet with a chair, but she recovers and pursues him to the edge of the cliff. Iridescent highlights glint on his bald head and skin—he’s beautiful, glorious. Why did Violet do this to him? he asks. Why did he give cancer to mice, she queries back. She’s done the same thing, used a lower life form to forward her aims. In the human Bible, doesn’t God give humans dominion over the other creatures of Earth? Well, her God demands she lead His lost children home.

Jeremy resists returning to the house. He can’t sleep: the sea calls him to come home. Violet takes his hand. It’s Dagon calling him, she explains. Welcoming him.

As they listen to Dagon’s voice in the waves, Violet rejoices in her first success and considers the work to come. Her sister will be a first willing volunteer, with the other lost children led home. Then she herself will finally go to her heart’s desire, deep down below the waves.

What’s Cyclopean: Violet uses Lovecraftian adjectives, mostly for human infrastructure. Roads spread in “fungal waves,” eel-like, their tentacles reaching across the world.

The Degenerate Dutch: Everyone agrees that it’s perfectly reasonable to use lesser species for scientific research. Not everyone who agrees on this is the same species.

Mythos Making: In Lovecraft’s original, “everything alive come aout o’ the water onct, an’ only needs a little change to go back agin.” In McGuire’s story, it takes a bit more effort.

Libronomicon: Kind of a pity this research will never end up in a peer-reviewed journal. Or not.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Everyone in this story seems pretty sane. Even the people who casually discuss cannibalism and imagine gutting bad drivers as a beauty treatment.

Anne’s Commentary

If the mark of a great fictional monster is constant imitation and re-evaluation, then the Deep Ones are rising in the ranks toward vampire/werewolf/zombie status. How should we think about these amphibious creatures? “Should” probably has nothing to do with it—we will each think of Deep Ones as we think of the world, as we think of our fellows, and even as we think of ourselves.

For purists, those who like their monsters irredeemably scary and evil, Deep Ones can be subaqueous devils extraordinaire, a horrific combination of shark and crocodile, toad and eel and malignant merperson. Thalassophobic Lovecraft naturally described them (and their smell) as repellent. If we believe legend and Zadok Allen, they’re simultaneously fond of sacrificing humans and mating with them. In Dagon and Hydra, they worship gods in their own loathsome images; worse, they’re associated with Cthulhu and shoggoths, and bad company doesn’t get much badder than that. They flop. They shamble. They croak. They stare out of lidless eyes, all squamous and slimy and stinking of seaside detritus, and they won’t float easy in the briny depths until they’ve destroyed or genetically polluted all humanity!

But what if we could walk in the Deep Ones’ webbed feet and view the world through their lidless eyes? Lovecraft himself is no pure monster purist—the narrator of “Shadow” achieves empathy with his former nightmares by proving to be one of them, and eschewing suicide for the glory that waits below Devil Reef. Whether the reader takes this development to be uplifting or grimly ironic may be diagnostic of his or her outlook on monsterdom in general, where the monster is indeed the ultimate Other.

Seanan McGuire’s “Down, Deep Down, Below the Waves” is a complex treatment of the Deep Ones, provocative (at least for me) of much uneasy thought on interspecies ethics. On the surface it might read as pure monster apology. When Violet treats humans the way humans treat lab animals, hey, all’s fair in the exploitation of lesser beings and obedience to one’s god, be that deity Science or Dagon. Jeremy protests that there’s a difference between him and a mouse. Is there? That’s the crux of the matter. Sure, Deep Ones are physically stronger, immortal, probably much older in sapience, possibly so attuned to their natural environment that they can do without the utilitarian technology of humans.

Or can they? However she disparages the god Science, Violet goes to great lengths to master its techniques—only through this “alien” knowledge can she do the will of Dagon and bring his lost children home. And who are the lost children? It seems they’re Deep One-human hybrids with too little of Dagon’s “seed” in their genetic makeup to return to the sea. The Innsmouth gift (or taint, depending on your outlook) seems to vary much in expression, even within families. Violet’s father transitions early, for he’s “purer” than her mother. Violet’s sister, older than Violet, hasn’t begun transitioning yet. Distant “children,” like Jeremy and Terry, will never transition without help. But even “purer” humans, like Christine and Michael, can transition partway, which suggests an ancient link between the species. There’s the matter of interbreeding as well, which further suggests shared ancestry. Be that as it may, the ancestry’s shared now, with so many hybrids running (and swimming) around.

So, is the evolutionary distance between Deep One and man enough to justify Violet’s experiment on unwitting subjects? Enough to justify Deep One consumption of humans? And would Deep One society be monolithic enough to answer either yes or no to the above questions?

Are McGuire’s Deep Ones right or wrong? Good or bad? Bafflingly mixed, you know, like humans? Does Violet triumph when she suppresses the sympathy for humans she’s acquired by living among them in their landlocked world? When she momentarily thumbs her nose at Science by violating her own research protocol in moving Terry to an ocean-view room? She’s not pure Deep One. Perhaps no child of Dagon is anymore, except Himself and Hydra. Does that make her saint to her Deep One part and sinner to her human part?

Intriguing questions, which proves the worth of the story inspiring them.

Last thoughts. Innsmouth seems as subject to reinvention as its denizens. McGuire’s upfront, I think, that her Innsmouth isn’t Lovecraft’s. She settles it in 1612, not 1643, and her settlers are “other” from the start, come to this isolated stretch of coast to keep traditions outsiders wouldn’t condone. There’s no sign of an industrial past in her town, nor any dilapidated relic of long economic decline. Instead it’s idyllic, an antiquarian’s dream of preserved houses, a naturalist’s of never-cut forest. The sole off-notes are those rusty cars in the Carver’s Landing parking lot. Violet notices this discrepancy in the perfect stage-setting, but then, she’s seen what the set imitates.

And what about Violet’s visions of her oceanic future? They suit her situation: self-exile-for-a-cause, looking forward to her reward of darting in the weightless freedom of the deep, sleekly beautiful and eternal, with Dagon’s song ever in her ears. I wonder whether she’ll find Deep One life so ideal, or whether Y’ha-nthlei doesn’t have its frictions and factions, its stratifications of Seabloods versus Landbloods, its everyday travails along with its grandeurs.

I hope so, to keep things interesting for her once the darting gets old.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

I’m picky about Deep One stories. Really, really picky. On the one hand, I have strong opinions about “Shadow Over Innsmouth.” My sympathies are always and ever with people who get shoved into concentration camps on the strength of unsubstantiated rumor. And Zadok Allen, 96-year-old town drunk, is as unsubstantiating as rumor-mongers come. On the other hand, if Deep Ones are jus’ plain folks with gills, why bother? These are, after all, people who are going to dwell amidst wonder and glory forever in many-columned Y’ha-nthlei. The sea is liminal, ineffable, beyond human scale. Something of that has to rub off on its denizens.

I have, therefore, no patience with stories in which Deep Ones are always-chaotic-evil child-sacrificing, puppy-kicking freaks. And I have little interest in stories where you could slot in any random aquatic humanoid in place of Dagon’s beloved children, without changing anything else. And… I absolutely adore this week’s story. “Down, Deep Down” walks its fine line with beauty and grace, and the sort of shivery, human-humbling comfort that I most desire from a good horror story.

McGuire skims close to another of my picky places: wildly unethical human subjects research. I spent over a decade running human subjects studies myself. Unless really good writing intervenes, I tend to get distracted by filling out imaginary IRB approval forms for mad scientists. More importantly, it takes a lot to make me sympathize with someone running destructive studies on sapients, and excusing it with racial superiority. Little things like the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment and Nazi hypothermia studies have for some reason made that sort of thing hard to sell. But again, “Deep Down” manages the trick. It faces the issue head on, as Violet comes to see her colleagues/subjects/definitely-not-friends as real people, and yet refuses to shy away from her self-imposed duty to, and desire to save, her own family.

I’d still reject the IRB application in the strongest terms possible. But Violet’s conflict rings true.

It doesn’t hurt that the scientific culture and practice hold up, as they usually do when McGuire’s ordinary researchers face extraordinary evidence. As the story doesn’t quite point out explicitly, there’s only a little difference between the cutthroat competition of a toxic academic environment, and Violet’s willingness to kill or non-consensually metamorphose her classmates For Science. Plenty of grad students would do the same solely for a publication, a decent postdoc, or just to complete the elusive last page of their dissertation. Jeremy, we’re told, “under the right leadership, could probably have been talked into some remarkable human rights violations.” Violet comes across, in this context, as not quite human and yet all too like humans, with all our dubious qualities.

As in any good Deep One story, longing for the water is central. Violet avoids her home for years, knowing it would be too hard to leave again once she returned. Her family promises that they never die in fire, only in water—and they refuse to fear it. When her classmates begin to change, it’s the sight of the ocean that makes the difference. “…the sea, which cannot be run from once the waves have noticed your presence.” So many good lines. Even those of us who lack Lovecraft’s phobias know that the sea deserves respect, both for its power and its mysteries.

Dagon and the Great God Science really do make a perfect pair.

Next week, for a change of pace, we’ll read a lovely pastoral romance: “Rappaccini’s Daughter” by Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Ruthanna Emrys’s neo-Lovecraftian stories “The Litany of Earth” and “Those Who Watch” are available on Tor.com, along with the distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land” and “The Deepest Rift.” Winter Tide, a novel continuing Aphra Marsh’s story from “Litany,” will be available from the Tor.com imprint on April 4, 2017. Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with the recently released sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.