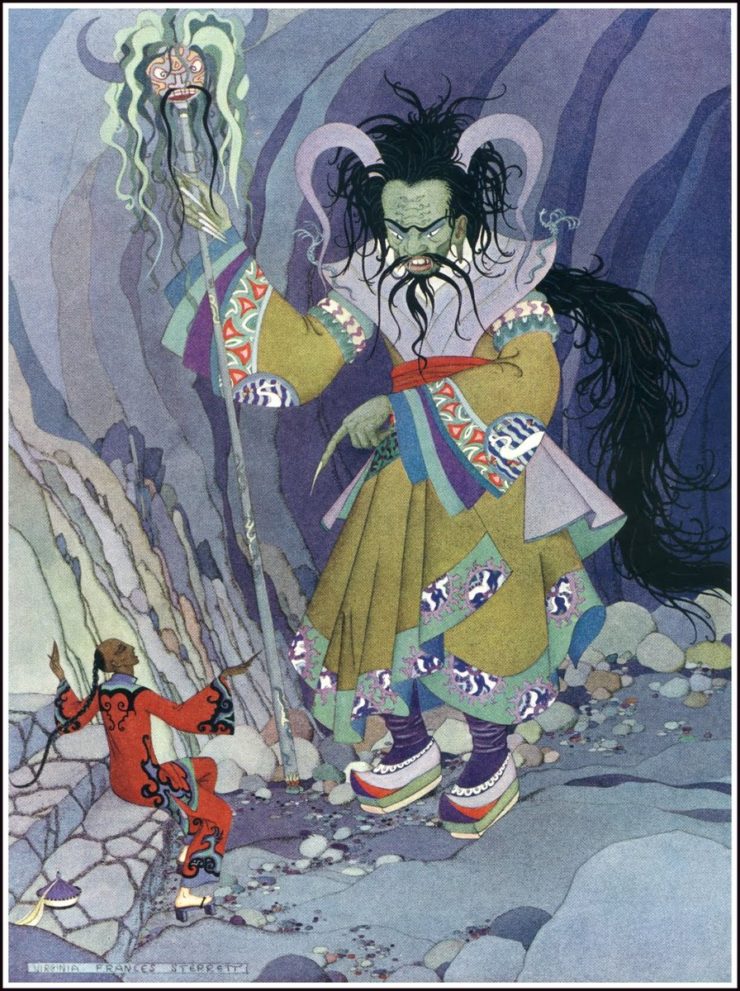

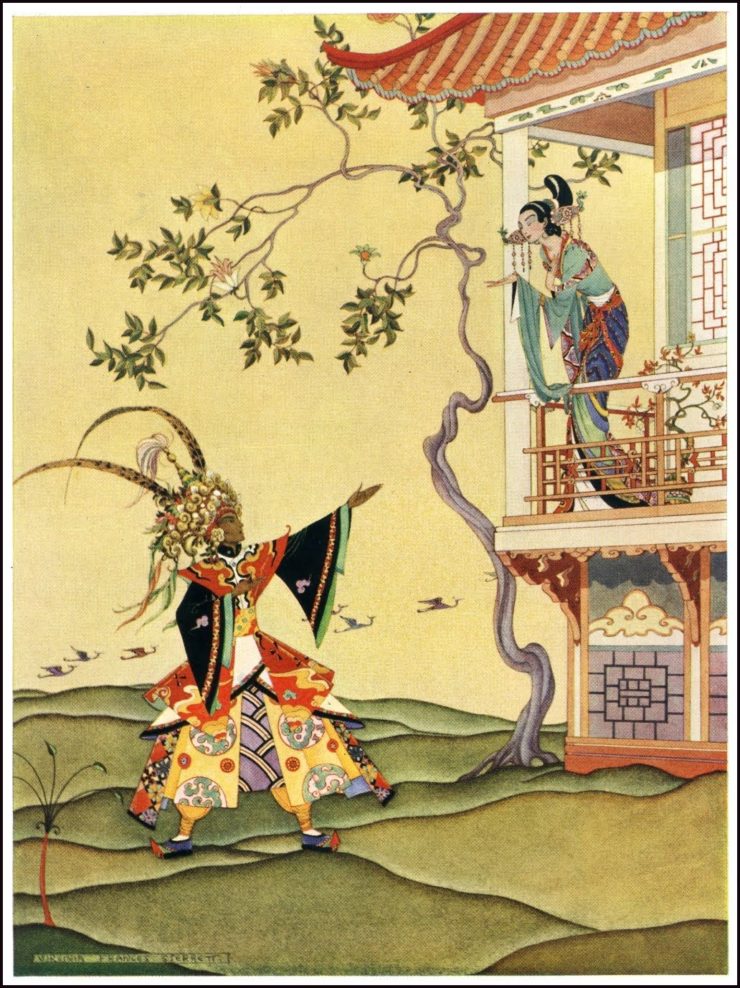

In Western literature, the best known story of the Arabic The Book of One Thousand and One Nights, also known to English readers as The Arabian Nights, is arguably “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp.” The classic rags to riches story of a boy and a magic lamp has been told and retold numerous times in numerous media, from paintings to poems to novels to films, helped popularize the concept of “genies” for European readers, and has even been used to sell certain types of oil lamps.

What’s great about all of this is that “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp,” isn’t actually in any of the original Arabic collections of The Book of One Thousand and One Nights at all. Also, it may not be Arabic, but French.

The Book of One Thousand and One Nights was brought to the attention of western Europe by French archaeologist Antoine Galland in the early 18th century. He had earlier enjoyed some success with a translation of a separate tale about Sinbad the Sailor, and also hoped to capitalize on the rage for fairy tales that had been popularized by French salon writers—the same writers producing the intricate, subversive versions of Beauty and the Beast and Rapunzel, which in turn were critiqued by Charles Perrault in Cinderella and, to a lesser extent, Sleeping Beauty. The fairy tales published by these often radicalized writers sold briskly, and Galland, who had read many of them, including Perrault, figured he had an audience. He was correct: his version of One Thousand and One Nights sold well enough to allow him to publish twelve volumes in all. They created a sensation, and were soon translated—from the French—into other European languages. The English translations of his French version remain better known than English translations of the Arabic originals today.

I said better known, not necessarily more accurate, or even at all accurate. As the 19th century English translator Andrew Lang later described the translation process, Galland “dropped out the poetry and a great deal of what the Arabian authors thought funny, though it seems wearisome to us.” This description of Galland’s process seems to be a bit too kind; indeed, “translation” is perhaps not the best word for what Galland did. Even his first volume of tales, directly based on a Syrian manuscript, contains stories that could be best described as “inspired by.” And even when he stayed closer to the original tales, Galland tended to add magical elements and eliminate anything he considered either too dark or more “sophisticated” than what his French audience would expect from “oriental” tales.

And that was just with the stories where he had an original manuscript source in Arabic. Seven stories—including Aladdin—had no such manuscript source. Galland claimed he’d recorded those stories from an oral source, a monk from Aleppo.

Maybe.

Scholars have been skeptical of this claim for a few reasons. One, by Galland’s own account, he did not start writing down the story of Aladdin until two years after he first supposedly heard it. Two, the story of Aladdin only begins to be recorded in Arabic sources after 1710—the year “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp” was first published in French. Three, unlike most of the stories that are definitely part of the original One Thousand and One Nights, “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp” is technically set not in Persia, India, or the lands of the Middle East, but in China and Africa. And four, parts of “Aladdin” seem to be responses to the later wave of French salon fairy tales—the stories that, like Cinderella, focused on social mobility, telling stories of middle and even lower class protagonists who, using wits and magic, jumped up the social ladder.

None of this, of course, means that “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp” couldn’t have been at least based on an original Middle Eastern folktale, retold by a monk from Aleppo, and again retold and transformed by Galland—just as the other French salon fairy tale writers had transformed oral folktales into polished literary works that also served as social commentary. It’s just, well, unlikely, given this questionable background story, and the way elements of “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp” appear to be direct responses to French stories. But that didn’t prevent the story from instantly becoming one of the most popular stories in the collection for western European readers—arguably the most popular.

Indeed, despite not being in the original Arabic collection, “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp,” proved to be so popular that it was added to virtually all of the many English translations of The Thousand and One Nights, including versions based not on Galland, but on the original Arabic manuscripts. Even the 19th century explorer and translator Richard F. Burton—who was highly critical of the Galland translations, saying that they were only abbreviated, inaccurate versions of the original Arabic tales, and who claimed to want authenticity in his translation—included it in his mildly pornographic translation that was otherwise largely taken directly from Arabic manuscripts, not the Galland versions.

The Burton translation, by the way, is amazing in all the wrong ways, largely because it contains sentences like, “Peradventure thine uncle wotteth not the way to our dwelling.” This, even more than the pornography, is almost certainly why that translation is not exactly the best known one in English, and why Andrew Lang—who wanted to present fairy tales in at least somewhat readable language—avoided the Burton version when creating his own translation, which in turn became one of the best known versions in English.

Lang may also not have approved of bits in the Burton version like, “Presently he led the lad [Aladdin] to the hamman baths, where they bathed. Then they came out and drank sherbets, after which Aladdin arose and, donning his new dress in huge joy and delight, went up to his uncle and kissed his hand…” For the record, this guy is not Aladdin’s actual uncle, and despite Burton’s alleged adventures in male brothels, I don’t really think this means what it might be suggesting, but this was probably not the sort of thing Lang wanted in a collection aimed at children, especially since Burton did deliberately leave sexual references and innuendos in his translations of other tales.

Thus, when compiling his 1898 The Arabian Nights Entertainments, his severely edited and condensed version of Antoine Galland’s collection, Lang ignored accuracy, original sources, and sentences like “And the ground straightaway clave asunder after thick gloom and quake of earth and bellowings of thunder” and even the greatness of “Carry yonder gallowsbird hence and lay him at full length in the privy,” and instead went for a straightforward translation of Galland’s tale that unfortunately left almost all of the details out, including the details that helped explain otherwise inexplicable references.

Lang also downplayed the references to “China” found throughout the story, and the vicious anti-Semitism and other racially pejorative remarks, along with several tedious, repetitive conversations where the speakers repeat what just happened in the previous paragraphs. Lang also deliberately chose to describe the main villain as “African” (a word frequently found in English translations of The Book of One Thousand and One Nights) instead of a “Moor” (the word used by Galland, and a word frequently found in French, Italian and Spanish fairy tales). And Lang left out some details that he knew were inaccurate—details that might have alerted at least some English readers that the story they were reading was perhaps not all that authentically Middle Eastern. It all led to the perception among later English readers of “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp” as a classic Middle-Eastern story, rather than as a pointed social and cultural commentary on French fairy tales and corrupt French government and social structures.

I’ve put quotes around the word “China” and “Chinese,” because the “China” of the story is not a historical or contemporary China. Rather, the “China” of “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp” is a mythical, distant land where it was completely possible for poor men and slaves to upset the general social order and remove corruption—something rather more difficult to do in lands Galland and his readers knew better, like, say, France, where, in 1710, said corruption was becoming an increasing issue of concern. This is not to say that these concerns were limited to France, since they certainly were not, but to suggest that French social concerns had more to do with the shaping of the tale than did Chinese culture. A grand total of zero characters have Chinese names, for instance. Everyone in the story is either Muslim, Jewish, or Christian (not unheard of in China, but not necessarily what western readers would expect from a Chinese story either); and the government officials all have titles that western Europeans associated with Middle Eastern and Persian rulers.

At the same time, the frequent use of the words “China,” “Africa,” and “Morocco,” serve as suggestions that “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp” and thus the social changes it emphasizes, takes place in the real world—in deliberate contrast to earlier tales told by French salon fairy tale writers, which take place in kingdoms that either have no name, or are named for abstract things like “Happiness” or “Sorrow.” In those stories, such changes are often magical, unreal. In Galland’s version, they may (and do) need magical assistance, but they are real.

Many of Galland’s readers would have understood this. Those readers also may have recognized the differences between the real China and the China of “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp.” By 1710, trade between China and France was, if not brisk, at least happening intermittently, and French readers and scholars had access to books that, while describing China more or less inaccurately, still allowed them to recognize that the “China” of “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp” was altogether fictional. Arabic and Persian traders had access to additional information. Whether Galland has access to those materials is less clear; if he did, he chose not to include them in what was either his original tale or a remembered transcription from an oral source, heightening his creation of China as both a real (in the sense of being located in a real physical place on this planet) and unreal (with all the details made up) place.

Meanwhile, using Persian titles for Chinese government positions not only helped to sell “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp” as an “Arabic” story, but was, for some 18th century French readers, only to be expected from “unsophisticated” Arabic storytellers. The same thing can be said for the anti-Semitic elements in the Galland version, which echo anti-Semitic stereotypes from France and Spain. It’s all suggestive—especially given that the story cannot be traced back to a pre-1710 Arabic or Persian source.

In any case, the main focus of “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp” is not accurate cultural depictions of anything, but political and social power. As the story opens, Aladdin is a poverty stricken boy not particularly interested in pursuing a respectable life; his mother’s various attempts to get him job training all fall through. Fortunately enough, an evil magician happens by, pretending to be Aladdin’s uncle, hoping to use the kid to gain control of a fabled lamp that controls a Marid, or genie. This fails, and the magician leaves Aladdin locked in a cave—with, however, a magic ring that allows Aladdin to summon a considerably less powerful Marid, and escape with the lamp and a pile of extraordinarily jewels. Shortly afterwards, his mother tries to clean the old lamp, which gives Aladdin and his mother access to the power of two genies and—in this version—seemingly unlimited wealth and power.

Here’s the amazing thing: Initially, Aladdin and his mother barely use this wealth and power. At all.

Instead, they order supper, which is delivered on silver plates. After eating, instead of demanding a chest of gold, or even just more meals, Aladdin sells one of the plates and lives on that for bit, continuing to do so until he runs out of plates—and starts this process all over again. This causes problems—Aladdin and his mother have been so poor, they don’t actually know the value of the silver plates and get cheated. They’re so careful not to spend money that Aladdin’s mother doesn’t buy any new clothing, leaving her dressed in near rags, which causes later problems with the Sultan. It’s an echo of other French fairy tales, where the prudent protagonists (always contrasted with less prudent characters) are aware of the vicissitudes of fortune. In Aladdin’s case, he has experienced extreme poverty and starvation, and he does not want to risk a return to this.

The only thing that does rouse him to do more is a glimpse of the lovely princess Badr al-Budur—a glimpse Aladdin only gets because he is disobeying a government order to not look at the lovely princess Badr al-Budur. To get to see her again, Aladdin needs money. But even at this point, Aladdin is surprisingly frugal for a man with the ability to control two genies: rather than ordering up more wealth, he starts by offering the jewels he previously collected from the cave where he found the lamp in the first place.

Aladdin only starts to use the lamp when he encounters an additional element: a corrupt government. As it turns out, the kingdom’s second in command, the Grand Wazir or Vizier, is planning on marrying off his son to the princess as part of his general plan to take over the kingdom. He thus convinces the Sultan—partly through bribes—to break his promise to Aladdin. To be fair, the Sultan had already agreed to this marriage before Aladdin offered a pile of exquisite jewels. Several broken promises on both sides later, and Aladdin finds himself summoning the genie of the lamp on the princess’s wedding night to do some kidnapping.

Aladdin kidnapping the princess is totally ok, though, everyone, because he doesn’t harm her virtue; he just puts a nice scimitar between them and falls asleep on the other side of the bed. She, granted, spends one of the worst nights of her life (emphasized in both translations) but ends up marrying him anyway, so it’s all good. And later, he arranges to put a carpet down between his new, genie created palace and her home, so that she never ever has to step upon the earth, which is a nice romantic touch. Admittedly, I can’t help but think that just maybe some of the princess’ later completely “innocent” actions that almost end up getting Aladdin killed have something to do with this, but that’s mostly me projecting here; the text makes no such claim. In the text, the kidnapping just makes the princess fall in love with Aladdin and after some more adventures with both genies and the evil magician they live happily ever after, since this is—mostly—a fairy tale.

Buy the Book

Desdemona and the Deep

But within the story, the important element is that the lower class, poverty stricken, untrained, unskilled Aladdin uses the genie to prevent the corrupt Vizier from gaining control of the government, and later to defeat a more powerful outsider—the magician. And he’s not the only character to act against a superior, either. The greatest act of defiance and working against evil and false leaders comes from an unexpected source—someone who is technically a slave.

That someone is the genie of the lamp. Technically, he must obey the owner of the lamp, just as the genie of the ring must obey the person wearing the ring. Technically, because in a powerful scene tacked on to the end of the story, the genie of the lamp flat out refuses to fetch Aladdin a roc’s egg—the very last thing Aladdin and his wife need to make their palace perfect. The story is, as said, tacked on—Aladdin has already married the princess, defeated the Vizier, defeated the evil magician, and saved his magical palace, seemingly bringing the story to a complete end, until out of nowhere the evil magician’s evil brother just happens to show up to threaten Aladdin here. He’s never been mentioned before, but his arrival allows the genie to rebel. And that, in turn, means that the happy ending of the story comes from a slave refusing to obey a master.

Indeed, “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp” is filled with such refusals—Aladdin refuses to obey his mother or his “uncle”; the princess refuses to obey her father; the vizier’s son refuses to obey his father. And these refusals all eventually bring happiness—or, in the case of the vizier’s son, continued life—to the characters. It’s in huge contrast to other French salon fairy tales, where characters are rewarded for obeying the status quo, even as their writers noted the stresses that could result from such obedience. Those stories, of course, were written down in the 17th century; by the early 18th century, Galland could note alternatives—even while carefully keeping these alternatives safely outside France.

“Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp” is a story where again and again, the aristocrats screw up or abuse the powerless, only to have the powerless turn on them. It’s also a story that discusses how easily ignorant people can be duped, with both Aladdin and the princess as victims, and also a story that strongly suggests that with poverty comes ignorance; with wealth comes job training. Aladdin has no idea how much the silver and gold vessels provided by the genie are actually worth, allowing him to get cheated. Once he has money, he spends time with goldsmiths and jewelers, for the first time learning something. That’s about the last time Aladdin gets cheated.

It’s not quite advocating for the complete overthrow of government—Aladdin ends the tale in charge of the entire country in a peaceful takeover from his father-in-law. The corrupt trader gets away—though since he did at least pay Aladdin for the items, if well below their actual worth, I don’t think we’re meant to worry about that too much. And “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp” has a number of other slaves, mostly black, some white, mostly summoned into existence by Aladdin and the genie of the lamp. These magically summoned slaves don’t get the chance to rebel or change their status much.

But still, for the most part, “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp” is a tale of sly rebellion, of the powerless taking control. That might help explain its appeal, and why it was translated multiple times into multiple languages, and adapted into other media—poems, novels, plays, paintings, dances, and films. Including a popular little animated feature where a boy promised to show a princess the world.

Quick final note: I’ve quoted some highlights from the Burton translation, because it’s so fabulously over the top, but be warned: if you do search out the Burton translation, available for free online, Burton left in all of the positive depictions of Islamic cultures (most of which Lang removed), at the cost of leaving in all of the virulently anti-Semitic material, and I do mean virulent. Some of the statements made about Moors and Moroccans (also removed by Lang) also contain offensive language. These statements can also be found in other translations of the Galland version, another reason why, perhaps, the Lang version remains one of the most popular.

Originally published in January 2016 as part of the Disney Read-Watch.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.