In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

Today, I’m going to look at another of the excellent single-author collections that Del Rey Books put out in the 1970s. In this case, the author is Raymond Z. Gallun, whose name I’ve seen mentioned frequently in science fiction histories, but whose work was unfamiliar to me. So, when I saw his fiction featured in one of those Del Rey collections, I ordered it online, and was rewarded with a diverse collection of quite excellent stories. Gallun is not as widely known today because much of his best fiction was of shorter lengths, and he was not prolific. But modern readers will find that his work is well worth a look, as it was quite innovative for its day.

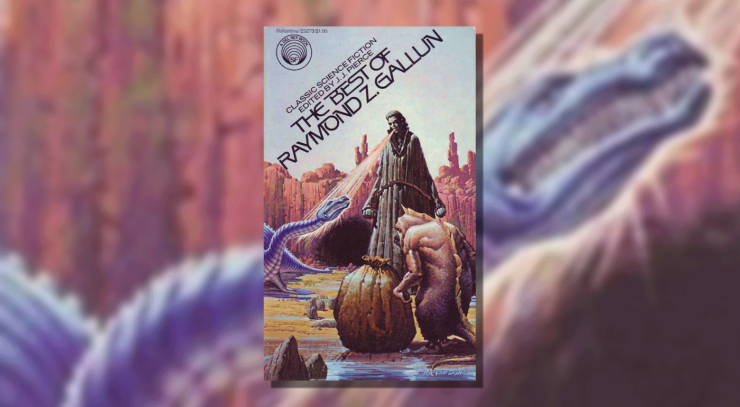

This volume of the “Best of…” series was published in August 1978, and has an intriguing cover by long-time Astounding/Analog illustrator H.R. Van Dongen.

About the Author

Raymond Z. Gallun (1911-1994) was a prominent American science fiction author who published a number of short works from the late 1920s to the mid-1960s, and a half dozen novels between 1951 and 1985. His early stories frequently appeared in Astounding magazine, while later work appeared in magazines like Galaxy and Planet Stories. He traveled extensively in the 1930s, and his experiences in different countries informed his fiction. He worked as a civilian employee of the Army and Navy in the Pacific during WWII. While he had been a prominent author in the field before the war, he largely turned away from writing science fiction after the 1950s, although he never stopped writing altogether. The Long Island-based science fiction convention I-CON has a lifetime achievement award named after Gallun, and a number of his stories are available to read for free on Project Gutenberg.

About the Editor

J.J. Pierce (born 1941) is a long-time member of the American science fiction community who has edited fanzines, books, and for a short time at the end of its run, Galaxy science fiction magazine. He has also published a number of critical essays and articles about science fiction and popular culture over the years, as well as a multi-volume history of the science fiction field.

Who’s the Best?

In his introduction to the collection, Pierce credits Gallun as one of a trio of writers who shaped modern science fiction in its early days, ranking him as an equal to John W. Campbell and Stanley G. Weinbaum. That is an audacious claim, and drops the reader right into the center of a favorite game of science fiction fans—debating which author is better, and who influenced who. But while I love that game as much as anyone, every writer has their own strengths and weaknesses, and attempting to rank them often seems like matching apples to oranges.

Stanley G. Weinbaum, an author whose work I adore (see my review of his “best of” collection here), emerged in the field like a fireball, with “A Martian Odyssey” and its strange aliens capturing a lot of attention right from the start. His work exhibited a great deal of humanity, and was filled with whimsy and even romance. But his untimely death, while it left the audience wanting more, also left fans wondering if he could have sustained and improved upon his original success.

John W. Campbell (see my review of his “best of” collection here), writing fiction under pen names, brought a new sense of seriousness and scientific rigor to the science fiction field. His editorial efforts at Astounding/Analog magazine had a profound impact. As most of the stories in this collection of Gallun’s work were published in Astounding, and fit the magazine’s house style, you might see that as reinforcing Campbell’s reputation. But the fact that four of them appeared before Campbell took the editorial reins of the magazine undercuts the argument that house style was wholly created by his editorial vision. Campbell also brought his prejudices and penchant for pseudo-science to his work, and many now view his legacy in a more complicated or negative light.

If I was to develop a list of the giants of the early pulp days of science fiction, I would have to include the work of Murray Leinster, an author whose career spanned from the teens to the 1960s, and who wrote pioneering stories of exploration, science, first contact, time travel, alternate worlds and even public health issues (see my reviews of Leinster’s work here, here, and here). But in the end, a lot of these lists and rankings come down to personal taste and preferences, and I’m sure all those who read older science fiction have opinions on the topic. So, let’s take a look at the stories in this collection, and see how the work of Raymond Z. Gallun stacks up…

The Best of Raymond Z. Gallun

After the glowing praise of J.J. Pierce’s introduction, the collection begins with “Old Faithful,” a gem of a first contact story. The story begins from the viewpoint of a Martian scientist named Number 774 (while using numbers for names is now a cliché, it was all the rage back in the day). Right from the start, 774 is described in a manner that shows he is totally unlike a human (in fact, applying a gendered pronoun to “him” seems to be a stretch). On the dying planet, while there are plenty of material and mechanical advantages, food and water are so scarce that there are strict population controls, and 774 has been declared redundant. He is an astronomer, who has established contact with intelligent beings on the third planet, using gigantic flashing lights, and learning Morse code to communicate. The viewpoint shifts back and forth to the astronomers on Earth with whom he is communicating, and their slow progress toward mutual understanding, starting with mathematics, is utterly convincing (and I say that as someone who is old enough to have used Morse code as a young coastguardsman). But the rulers of Mars see no practical use for 774’s discovery, and having no future, he decides to risk his life to travel to Earth. He has his robot minions build a spaceship, which he uses to intercept a comet, then employs the comet’s gravity to tow him toward Earth. By the end of the story, I was rooting for this strange creature, and inspired by his bravery and thirst for knowledge.

In the story “Derelict,” Jan Van Tyren is a broken man, returning to Earth after his family was killed during a native uprising on the Jovian moon Ganymede. He finds an ancient alien spaceship, his curiosity overcomes his ennui, and he boards it to investigate. He finds a robotic creature that immediately takes actions to control his emotions—knowing the story came from a time when aliens often proved to be evil monsters, I became suspicious, fearing malicious intent. But the story goes in a whole different direction, and it ends up being another touching tale, with a strong emotional core.

In “Davey Jones’ Ambassador,” a man is kidnapped by a deep-sea civilization that has existed without the knowledge of humanity. The efforts to find common ground between members of those two civilizations are interesting, but the most fascinating element of the story is its description of an advanced civilization that has developed without the use of fire.

The longest story in the collection is the novelette “Godson of Almarlu,” a tale packed with enough ideas to fill a novel. It starts with robotic creatures entering a nursery and modifying the brain of a sleeping child. That child, Jefferson Scanlon, grows to be a giant of industry and a prolific inventor, given to manic periods of creativity. He eventually builds a gigantic laboratory in the Arctic, just as the Earth begins to tear itself apart in an explosion of volcanic activity. People begin to blame Scanlon, whose laboratory is sucking air and water from its surroundings and propelling it toward the moon. What those people don’t realize is that there is a body in the solar system made of solid neutronium, and it is this body’s enormous gravity that is tearing the Earth apart. The robots that tampered with Scanlon are one of the last remnants of Almarlu, the fifth planet of the solar system, torn apart and turned into the asteroid belt, designed to help the next planet that faces this threat. As nations dispatch bombers to destroy him, Scanlon urges people to fly any aircraft they can into the pillar of air and water and travel to the moon, where the remnants of humanity can recover and rebuild. While neutronium was a topic of speculation at the time, Gallun appears to have been the first to contemplate how a body composed of the hypothetical substance would behave, and what impact a world in a long eccentric orbit could have on the solar system. And, as in his other stories, the people Gallun creates are a cut above the cardboard characters that filled other pulp tales of its era.

“A Menace in Miniature” is a mystery story where a spacer and scientist are trying to figure out what killed previous visitors to a new world, including the rest of their team. It unfortunately hinges on the old cliché of a lone scientist with little to work with making a scientific breakthrough, which always undermines my suspension of disbelief.

Gallun takes us to the distant future of the solar system in “Seeds of the Dusk.” As spores of an alien civilization of intelligent plants move inward from the outer reaches of the solar system, the ruthless descendants of humanity, huddling underground on Earth, plot to exterminate the inhabitants of Venus—and after departing to take over that world, to also destroy the flora and fauna of Earth to help stop the spread of the alien spores. It is a quirky tale, with one of the viewpoint characters being an intelligent crow, but works as a cautionary tale about the price of hatred.

There follows a quartet of short stories that, while clever, don’t stand out from the crowd. In “Hotel Cosmos,” a hotel security chief works to protect diplomatic efforts in a hotel whose rooms offer alien representatives different atmospheres and environments. “Magician of Dream Valley” takes a journalist to a distant part of the moon, where he is enlisted by a scientist who wants to save the flickering lights that inhabit the region, which are being destroyed by a human rocket fuel plant. But nothing is as it seems, and the man is faced with a terrible choice between his own race and another. “The Shadow of the Veil” is a compact little morality tale where human con men using a statue to cheat aliens, only to find they should have researched their marks more carefully. “The Lotus-Engine” is an atmospheric tale where two human explorers revive alien technology in the ruins of an ancient civilization, and are lucky to escape with their lives.

The story “Prodigal’s Aura” is one of my favorites in the collection. David and Mattie Jorgensen and their children live out a staid existence on their Minnesota farm. When Augie, Mattie’s space-faring brother-in-law, visits the farm, his tales of adventure enthrall everyone except David, who has grown weary of his exaggerations and constant requests to borrow money for get-rich schemes on the outer worlds. Augie has a new money-making scheme to grow Martian seeds on Earth, but a dropped suitcase and gusty winds spread the seeds randomly, and the rest of the plot is driven by the threat of invasive plants from other worlds. The heart of the tale, however, lies in the far more interesting evolution of the relationships between the characters.

A couple find that their extended lives bring boredom in “The Restless Tide,” and after struggling to find meaning in life on an over-developed Earth, emigrate to start over as pioneers on Saturn’s moon, Titan. The story is considered one of Gallun’s best, but I myself have always found stories about bored immortals rather tedious, so I didn’t care for it.

In the last story in the collection, attracted by the lure of abandoned Martian ruins, one person flees the confines of human settlements on Mars in “Return of a Legend.” Searchers begin to disappear as well, as more and more settlers end up following the call of the wild.

The book has an afterword written by the author in 1977, looking back at the stories in the anthology, and his career in general. He states that his favorite aspect of early science fiction was the sense of wonder and optimism, and that “The Restless Tide” was his favorite story.

The collection definitely showed me why the name Raymond Z. Gallun is so frequently mentioned by science fiction historians. While his work shows some of the flaws of its era—with his prose sometimes being florid, nearly every world in the solar system being habitable, a lack of female characters, and some improbable science—there are key elements that definitely separate him from the pack. His aliens are convincingly alien, his human characters well drawn, and there are some examples of solid scientific extrapolation that are ahead of his time. His stories also have a lot of heart, and a sense of wonder that makes them shine.

Final Thoughts

I’m glad to have found this collection, as Gallun is indeed a science fiction author worthy of note, who deserves to be more widely remembered. While some elements of his work have become dated, his stories have a lot of energy and spirit that make them attractive to modern readers.

And now its your turn to join the discussion: If you’ve read any of Gallun’s work, I’d like to hear your impressions. And I’d also like to hear your thoughts on the best science fiction authors from the pre-World War II era. J.J. Pierce has nominated Gallun, Weinbaum, and Campbell, I’ve suggested Leinster, and I’m sure there are more who are worthy of note.

I went to check on Mr. Gallun being a Cordwainer Smith Rediscovery Award winner, and I am surprised to find that he has not been given this award. And just to make sure that perhaps he is still well-known enough to avoid “rediscovery”, I checked and found Stanley Weinbaum (2008) on the award list. So it looks like he is being overlooked by the folks who wish reduce the overlooking of early pioneers.

And if I were adding names to a pre-WW 2 sf/f list, I would include Jack Williamson, though I suppose we could argue that the bulk of his career was in fact post-WW 2, given that he was winning Hugo/Nebula awards in 2001.

I enjoyed Gallun’s work, first finding it the old anthology (Adventures in Time & Space of pre WW II SF). The Best ofis good; I also liked an early 60’s novel The Planet Hoppers

I think you meant “The Planet Strappers,” which was an early ’60s Raymond Z. Gallun novel.

I remember “Seeds of the Dusk”, despite having read it a long time ago – the hibernating crow in particular stuck in my mind. I hadn’t realized that it was first published in the 1930s – Gallun was somewhat ahead of his time in his attitudes.

There was another Gallun short story, can’t remember the title, but it was told by a palaeontologist, excavating a dinosaur site, who was approached by someone saying he was a time traveller who had visited this same site in the Mesozoic and produced photographs of the living fauna of the time. When he was back there he encountered extraterrestrial travellers engaged in some sort of internecine conflict. I remember being impressed by Gallun’s knowledge of contemporary palaeontology (out of date now – this is another real oldie – but he at least did some research).