“Romance reader” is such a broad term, and one that is often mistaken and misused. To those not au fait with the many subgenera that exist within the wide and wonderful playground in which we so gleefully spend our time, too often a “romance novel” is considered synonymous with a “trashy novel.”

Category lines like those of Harlequin and its ilk are held up as exemplars of the field, and—if we’re lucky—best-selling tearjerkers from the likes of Nicholas Sparks are considered romance—and are then subsequently dismissed as “mere” romance.

This ignores the rich history of romantic fiction. From myths of Greek heroes to Arthurian legends, from Sir Walter Scott and Lord Byron to Anna Karenina, The Scarlet Letter, and almost anything involving the French Revolution, timeless romances have repeatedly played out across the spectrum of Classic Literature. And what was Shakespeare if not a writer of romance? Although they may have been regarded as such as the time, these were certainly not cheap tales of Happily Ever After or Doomed Love; they were not simplistic wish-fulfillments of an average girl becoming a princess, or lust-fuelled accounts of unbearably hot vampires and their destined life mates. (Not that there’s anything wrong with any of that—at all.)

Such old school romance involved the great and the good, the mighty and the corrupt, offered up ruminations on the human condition and often required searing, but life-affirming, sacrifice. These are tales of eternal, elegiacal adoration—Orpheus and Euridyce, Lancelot and Guinevere, Tristan and Isolde—hell, even Rhett and Scarlett—tales that cry out to us through the ages to be treasured and relived, their exquisite tragedies lamented again and again.

Aside from in fictionalized biographical accounts of historical figures (I, Claudius, anything by Philippa Gregory, etc.) and to a lesser extent in the overwrought family sagas of a Catherine Cookson or a Danielle Steele, it is difficult nowadays for the discerning romance reader to really get back to those early, rarefied roots.

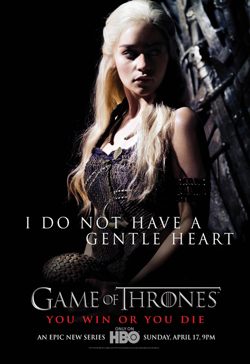

Difficult, that is, until you realize there is still one arena of artistic endeavor in which stories that honor the traditions of romantic fiction, in all its terrible, beautiful glory, still exist: epic fantasy. And nowhere in the genre better exemplifies this than George R. R. Martin’s A Game of Thrones, the first in his wildly, almost fanatically successful series, A Song of Ice and Fire. First published in 1996, and finding its way to HBO on April 17, this sweeping account of love, honor, duty, envy, mystery and conspiracy—along with an inordinate amount of ill-fated eavesdropping carried out by one particular family of adorable and scapegrace children—hearkens back to the early notions of romance, where you are flung into a world of tenderness and treachery, devotion and deception, and can only hold on tight as you navigate every labyrinthine twist and turn, never quite sure where you’ll end up but breathlessly enjoying every minute of the ride.

Now, some readers hear the word “fantasy” and immediately conjure for themselves visions of wizards in pointy hats, elves, golden rings and long treks to Mordor. (Thank you, Tolkien.) They think sword and sorcery, dragons, or Dungeons and Dragons, and fear the stigma that comes along with being a proponent of such things. But the fact is, many who don’t consider themselves fantasy readers already are: Diana Gabaldon, Lynn Kurland, Nora Roberts, et so very al.

And while A Game of Thrones (and more particularly, its successors: A Clash of Kings, A Storm of Swords and A Feast of Crows, with a fifth novel, A Dance of Dragons—yes, okay, there are dragons here—due out this July) can certainly be termed sword and sorcery, it is so very much more than that.

On the magical front, it is worth noting that such arcana is barely even mentioned until about halfway through the first book. (And this is not a short book.) As for the swordplay side: sure, it’s here, and is detailed lovingly, but Martin’s prose is lyrical and yet spare, giving us gorgeously rendered battle reports without ever drifting into the overly-technical or getting mired down in his own tactical cleverness. The society in which we largely find ourselves, The Seven Kingdoms, is patriarchal, martial, and medieval. There are great lords and their corresponding serfs; there are young women forced into political marriages and, even more irksome, expected to enjoy ceaseless embroidery. There is a wicked queen and a war bidding fair; there are power mongers and corrupters of innocence; there are those who have been driven insane by grief or manipulation or addiction; there are warnings gone unheeded and frankly idiotic actions undertaken by those who should know better (Eddard and Catelyn: looking at you); and there is vulgarity, effrontery, and stone-cold reality flung at us with not a single care for any reader of more delicate sensibilities.

This is a chronicle of heroism and heartbreak, of valiance and vengeance; it is most assuredly not a Happy Ever After, but in between the intrigue and the incest, the confronting imagery, careless brutality and frustrating misrule, there is a core of decency, of nobility and, yes, of romance. Our characters are multi-faceted and complex, and many of them you will hate, even if they are nominally “good” (note to Sansa: die horribly), but even the irredeemable and venal have within them the capacity for love, whether it be for family, king, country or mate, and it is these depths of feeling that not only drive their frequently tragic actions but also, when it comes right down to it, the many-splendored plot.

A Game of Thrones kicks off A Song of Ice and Fire in soul-rending, heart-stopping form; it is not unalloyed delight but is utterly unforgettable and, like those passionate stories out of myth and legend that have since become part of the popular consciousness, will long endure. This book—and, indeed, series—is not really what one might term romantic fantasy, or even romance at all, in today’s parlance. But when ranged alongside the great, tempestuous epic romances of all time, Martin’s epic fantasy tale is most assuredly one for the ages.

This article and its ensuing discussion originally appeared on our sister site, Heroes & Heartbreakers.

Rachel Hyland is the Editor in Chief of Geek Speak Magazine, cannot wait for April 17, and is pretty sure Sean Bean was born for the role of Lord Eddard.