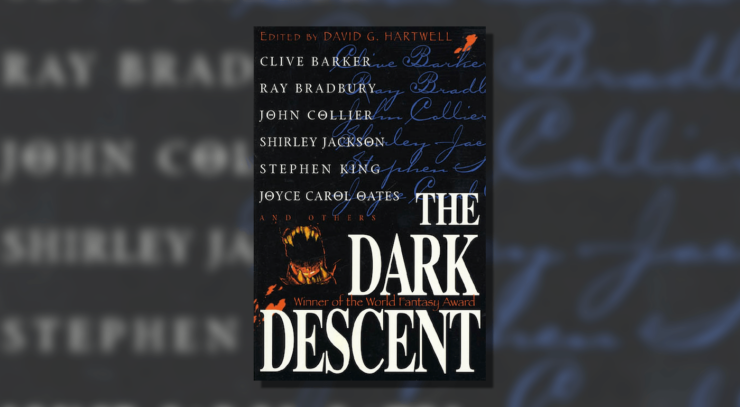

Welcome back to Dissecting The Dark Descent, where we lovingly delve into the guts of David Hartwell’s seminal 1987 anthology story by story, and in the process, explore the underpinnings of a genre we all love. For an in-depth introduction, here’s the intro post.

Fritz Leiber has a gift for marrying the gothic with the mundane. His most famous creation, the Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser series, features two pragmatic rogues more interested in the next score than in any grand world-saving designs who nonetheless get involved in numerous dark fantasy escapades. Some of his best stories (“Gonna Roll the Bones” and “The Automatic Pistol,” for example) are about relatively average people forced to confront the larger insanity of the world around them. “Belsen Express” continues this trend handily, forcing an irascible middle-class conservative man into a gothic morality tale where he’s beset by (and eventually meets his demise at the hands of) nightmares of being horribly murdered under a fascist regime. Through the eyes of George Simister, an average (but atypical for gothic horror) protagonist, Leiber uses a gothic morality framework to indict those who experience the atrocities of the world at a distance but refuse to fully understand, process, and confront the very real horrors around them.

George Simister is a comfortable, middle-class, conservative man in the 1950s, happy to pass judgment on the events of the world from his easy chair by the fireplace. Having avoided most of the horrors of the twentieth century due to his weak heart and self-interest, he nonetheless harbors an irrational fear that in the middle of the night he will be dragged out of his bed by the Gestapo. When a mysterious (and possibly misdelivered) package containing books on Nazi atrocities lands on his doorstep, Simister’s comfortable life takes a turn for the unnerving, his hallucinations and nightmares leaking into his daily life. As his sanity erodes and his walls come crumbling down, it might be too late for Simister to avoid his nightmares becoming uncomfortable reality.

“Belsen Express” has all the hallmarks of a gothic morality tale. There’s an ambiguity to the horror elements, erring mainly on the side that Simister’s torment is one cooked up by his mind, but with enough room for doubt. The protagonist is introduced sipping scotch and reading the paper by the fireplace (and engaging in some casual racism as he mutters to himself) when a mysterious package is dropped on his doorstep, and there’s an element of morality tale in the way that an irascible man with politically conservative views and prejudices is tormented by hallucinations and ominous figures related to his fears. This is matched by the ambiguity of his death, with both the fact of his weak heart (the thing that probably kept him out of direct conflict during the war) and being gassed by spectral Nazis treated as equally possibly explanations for his sudden demise. Leiber even structures “Belsen Express” like a gothic story, with Simister’s mental state deteriorating as the horror elements kick further into gear, ending with his final breakdown.

With that in mind, Simister is (as noted above) an atypical target for gothic retribution. He’s an unpleasant man, but not an active sadist like Justice Harbottle. Nor is he a sympathetic victim like the protagonist of “The Crowd.” Leiber depicts him as aggressively middle-class, with mention that the scotch he’s drinking by the fireplace is cheap and diluted, and his house (“the most respectable and best-kept” home on his block) constantly a target for local vandalism from the neighborhood youths. Even his complicity in events is minimal at best, since he’s at a remove; He’s introduced as “having survived well through the middle of the twentieth century without getting involved in military service, world saving, or any activities that interfered with the earning and enjoyment of money.” The closest he gets to any kind of actual political consciousness is bickering with his “friend” Holstrom and his secret fear that he’ll be scooped up by some kind of totalitarian regime and exterminated. He even starts questioning himself when the mysterious books are dropped on his doorstep, at which point he’s forced to confront the Nazi atrocities he vehemently tries to ignore. While Simister is unpleasant and acutely self-interested, he’s also aggressively average and capable of being emotionally and intellectually swayed when the distance and comfort he enjoys is stripped away.

In this way, the story feels like a much nastier version of “Young Goodman Brown.” Simister’s inability to process and confront the realities he’d distanced himself from causes him to spiral into madness and forces his horrors into his daily life. Leiber does an excellent job of meshing Simister’s nightmares with his daily commute, with each repeated morning journey growing more sinister (you have no idea how hard it is not to mistype that word in this article), paranoid, and totalitarian the further he’s beset by his nightmares. His refusal to confront the horrors of the world, knowing that awful things are going on but choosing to avoid them until incontrovertible proof literally lands on his doorstep proves to be his undoing. His fear that he will be rounded up and exterminated—however irrational—is a sign that he knows awful things are happening, that “it can’t happen here” is a false statement of comfort. It’s a widening crack in the wall of his unpleasant, smugly conservative distance.

A lot of “Belsen Express” deals with that level of distance and non-involvement. Simister’s torment begins when he’s sent a series of books confronting him with the horrors of the Holocaust, which exacerbate his already existent (if irrational and actively suppressed) fears. Holstrom engages Simister in constant political arguments, but neither of the men is directly affected by the issues they argue about. Even the inciting incident that spirals Simister into madness—Holstrom sending him the books—was meant as a prank. It’s important that the moment Simister’s torment by shadowy fascists starts is the moment all distance is removed from his life. When he’s confronted with the reality of the atrocity, he breaks down, and that’s when the strange knockings, suspicious-looking man in the overcoat, and threatening guard at the train station show up. By the time he starts to process the horror, it’s already too late.

“Belsen Express” might be atypical to gothic morality, but that’s entirely Leiber’s point. It’s cathartic to watch the privileged get dragged off to Hell, but it’s also easy for most people to distance themselves the same way Simister does. There’s an idea that bad things will mostly happen to other people at enough of a remove that the average person internalizes it only as a vague, abstract fear. With “Belsen Express,” Leiber removes that abstraction and tears down the walls, forcing the reader to understand that we must confront these things lest we be consumed by the horror we seek to tune out. It’s easy enough to sit someplace and pass judgment, to argue and harangue in the abstract the way Simister and Holstrom do. It’s a little harder to bear witness, comprehend, process, and confront those horrors. Leiber’s point is that we must, that we can’t live in comfort and abstraction.

After all, one day the horrors might show up on our doorstep the way they did Simister’s.

And now to throw it over to you: For those who’ve had brushes with Leiber, comment with your favorite non-Fafhrd and Gray Mouser work of his. Apart from that, I’d also like to know your favorite non-traditional gothic morality stories.

Please join us in two weeks as we explore the other serial murderer that inspired multiple works from Robert Bloch in “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper”