“I am told there are people who do not care for maps,” Robert Louis Stevenson wrote in 1894, “and find it hard to believe.” Stevenson famously began Treasure Island with the map:

[A]s I paused upon my map of ‘Treasure Island,’ the future character of the book began to appear there visibly among imaginary woods; and their brown faces and bright weapons peeped out upon me from unexpected quarters, as they passed to and fro, fighting and hunting treasure, on these few square inches of a flat projection. The next thing I knew I had some papers before me and was writing out a list of chapters.

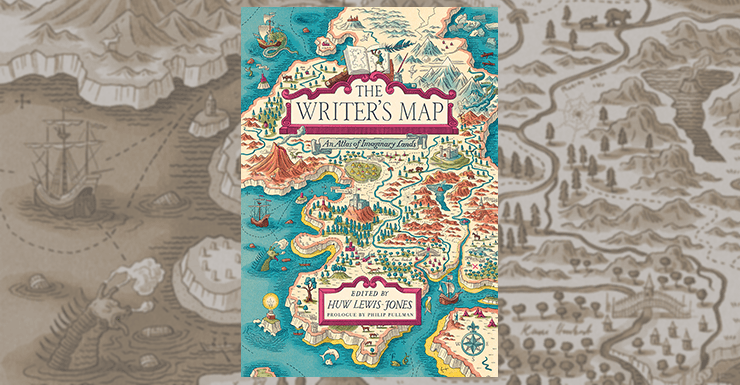

Other writers have begun their worldbuilding with a map; others build maps as they go; and while some go without maps altogether, the fact remains that for many writers, the maps are an intrinsic part of the creative process: as a tool or as sources of inspiration. That relationship, between the map and the act of literary creation, is the subject of a new collection of essays and maps, The Writer’s Map: An Atlas of Imaginary Lands, edited by the historian of exploration Huw Lewis-Jones.

The Writer’s Map does two things: it collects writing about literary maps and it presents those maps pictorially. We’ve had collections of literary and fantasy maps before—for example, J. B. Post’s Atlas of Fantasy, the second edition of which came out in 1979, so we’re past due for another. We’ve had essays about literary maps, published here and there in periodicals, essay collections, and online. This book gathers them both in one place, creating what is nothing less than a writer’s love letter to the map.

First, let’s talk about the maps included in this book. There are a lot of them, all immaculately reproduced. Naturally there are maps of imaginary lands, per the title: not only modern favourites (Narnia, Middle-earth, Lev Grossman’s Fillory, Cressida Cowell’s Archipelago from the How to Train Your Dragon series), but also some older maps you may not be familiar with, though the overall emphasis is on modern children’s and young adult books. The bog-standard fantasy maps from adult epic fantasy series, about which I will have more to say in future posts, aren’t as well represented; frankly, the maps here are much better.

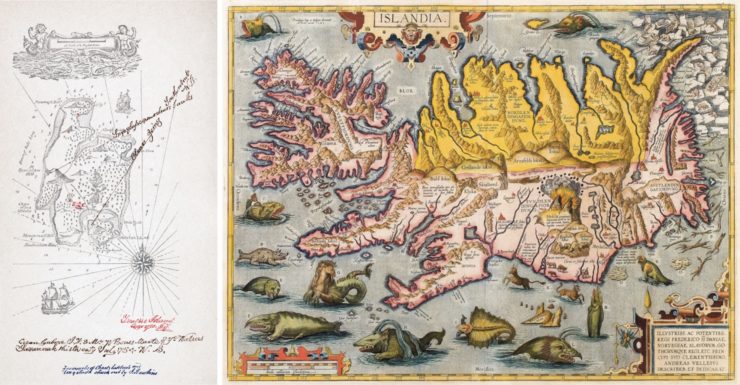

These maps share space with a wealth of (preponderantly European) medieval and early modern maps of the real world: mappae mundi, portolan charts, and maps from the earliest atlases. These, too, are lovely to look at, and their inclusion could be justified on that basis alone; but their connection to modern fantasy maps, or to a book ostensibly about imaginary lands, per the subtitle, is not immediately apparent. The answer is in the text, and has a bit to do with dragons.

A lot of map books are published in the second half of the calendar year (the clear implication: these make great gifts), and like most of them, this one can be enjoyed with little regard for the text. But, again like most most map books, this one is worth reading for the articles. The Writer’s Map’s thesis is set out by Lewis-Jones in the three essays he wrote himself (one in collaboration with Brian Sibley). He connects modern fantasy with early modern and nineteenth-century traveller’s tales, adventure fiction and travel narratives. The imagination is drawn to places that exist in the imagination: these places once included the metaphorical and the unexplored; once the globe was explored, the tradition continued in fairy tales and fantasy novels. “Faerie,” he writes, “is not so far from the kinds of places gathered together in The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, a tale that astonished readers way back in the 1360s” (p. 235).

Another connection is the margins of maps. On medieval and early modern European maps the margins were covered in sea monsters and other marginalia, a practice catalogued by the cartographic historian Chet Van Duzer in his 2013 book Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps. (Ortelius’s Theatrum Orbis Terrarum or Magnus’s Carta Marina come to mind.) More recently Van Duzer has been exploring the cartographic practice of leaving no empty space unfilled: he argues that the artistic concept of horror vacui applies widely to maps of that period. Whereas empty spaces, as I argued in a 2013 article in the New York Review of Science Fiction, are a hallmark of fantasy maps. But to follow Lewis-Jones’s argument, a map surrounded by monsters and a map surrounded by empty spaces are not so different. A phrase like “here be dragons”—used seldom in real life (one of two places is the Hunt-Lenox globe) but over and over again in fiction—may have served as a warning, either of unknown dangers or unreliable cartography, but for those attracted to uncharted seas and unmapped lands—aficionados of adventure, travel and fantastic tales—such a warning is absolute catnip.

The endurance of dragons at the borders of maps speaks to a theme not just of mapmaking, but of storytelling itself. As travellers and readers, we want to find ourselves in these borderlands. We have an urge to go to places where we are not sure of what is going to happen. And this is exactly where writers often position the reader: close to the real world, but also near the edges, where thoughts and things work in unexpected ways. (p. 229)

Explorers and fantasy readers alike want to go where the dragons are.

So too do the writers. “Maps in books call to us to pack a knapsack and set off on a quest without delay,” says children’s mystery writer Helen Moss in one of the two dozen additional essays (p. 138). Coming from both writers and illustrators, these essays do the bulk of the work exploring the relationship between map and story, artist and writer. It’s by no means a one-way relationship: in Part Two, “Writing Maps,” writers talk about how their imaginations were fired by a map they encountered in their childhood (surprisingly common!), or how they, like Stevenson, worked out the details of their worlds on a map before setting words down on paper, or share their perspective on how their little sketches were turned by an artist into the finished map. The bulk of the authors write children’s or young-adult fantasy: for example, we have a prologue by Philip Pullman and essays by Cressida Cowell, Frances Hardinge, Kiran Millwood Hargrave, and Piers Torday; we also have contributions from Abi Elphinstone, Robert Macfarlane, Joanne Harris, and David Mitchell.

Buy the Book

The Writer’s Map: An Atlas of Imaginary Lands

The tables are turned in Part Three, “Creating Maps,” in which the mapmakers talk about the literary works that inspired them. They include Miraphora Mina, who created the iconic Marauder’s Map prop for the Harry Potter films; Daniel Reeve, whose maps for the Lord of the Rings films have arguably overtaken the Christopher Tolkien original and the Pauline Baynes poster map in terms of their influence on fantasy map design (I’ll have more to say about that in a later post); Reif Larsen, author of The Selected Works of T. S. Spivet, who explains how he came to the conclusion that that first novel had to include maps and diagrams made by its 12-year-old protagonist; and Roland Chambers, whose maps for Lev Grossman’s Magicians trilogy delighted me in how they represented a return to the simplicity of Baynes and E. H. Shepard without the freight of later epic fantasy maps.

Part Four, “Reading Maps,” I can only describe as a series of lagniappes, pieces that fill in the corners but don’t otherwise belong: Lev Grossman on role-playing games, Brian Selznick on maps of the body, Sandi Toksvig on the erasure of mapmaking women.

All of these essays are interesting but ultimately personal: what synergy there is in The Writer’s Map can be found in the multitude of voices that establish, again and again, through anecdote and experience, that maps and words share the same creative impulse and are two sides of a worldbuilding whole. “Most writers,” says Lewis-Jones, “love maps” (p. 20); in the end, a map of an imaginary land is literally loved into being.

The Writer’s Map is available from the University of Chicago Press in North America and from Thames and Hudson in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth. Excerpts can be found online at the Guardian, Literary Hub, and The New Yorker.

Jonathan Crowe blogs about maps at The Map Room and reviews Canadian science fiction for AE. His sf fanzine, Ecdysis, was a two-time Aurora Award finalist. He lives in Shawville, Quebec, with his wife, their three cats, and an uncomfortable number of snakes. He’s on Twitter at @mcwetboy.