In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

Browsing through my local used bookstore recently, I ran across an old anthology from 1970 with a cover blurb promising “Heroic Tales told by Lin Carter, Fritz Leiber, John Jakes, Leigh Brackett, and a novella by Poul Anderson.” Just those names alone were enough to draw me in, especially when a scan of the table of contents showed I had only read one of the stories listed. I have also been on a Leigh Brackett kick lately—having encountered only a few of her works in my youth, I’ve been making up for that by grabbing everything I can find with her name on it. The collection turned out to be well worth my time and full of fun adventure stories, even though only three out of the five stories actually feature heroes who wield swords!

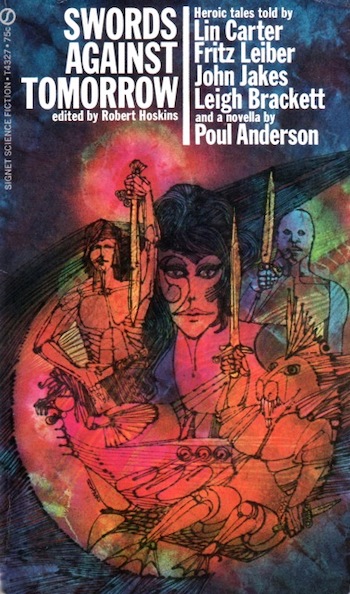

I picked up this book as part of my continuing quest to find good summer reading, which to my taste should be nothing weighty, and feature enough adventure and excitement to keep me turning pages…and this book hit the spot. As I’ve mentioned, it was the list of authors that initially drew me in, as the cover illustration is one of those unfocused and impressionistic line drawings popular at the time, a style that never appealed to me. Again, the title is not entirely accurate, making me suspect there may have been some disagreement behind the scenes regarding what the book should be called. The title Swords Against Tomorrow doesn’t really fit, as only one story is set explicitly in the future, and not all the stories feature swords. There is a common thread between the stories, however, and that is adventure. The collection offers work from five excellent authors at the top of their game, and each story, in a slightly different way, delivered the excitement, action, and adventure I crave from this type of fiction.

About the Editor and Authors

If I had ever come across the work of editor and author Robert Hoskins (1933-1993) before, I had forgotten his name. He wrote about a dozen novels, but was more widely known as an editor, working for Lancer books and compiling several anthologies.

I haven’t yet discussed the work of Lin Carter (1930-1988) in this column, although I read a good bit of his work in my youth. For more than any fiction of his own, I knew him as one of the editors and authors involved in collecting and expanding Conan’s adventures for Lancer Books. His work was primarily in the sword and sorcery and planetary romance sub-genres.

Fritz Leiber’s (1910-1992) Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser tales are among my favorites, and you can find biographical information in my earlier review of a collection of their adventures.

John Jakes (born 1932) began his writing career in science fiction, creating the sword and sorcery character Brak the Barbarian. But most look at that period as a warm-up for the historical fictional works that made him famous. This includes the Kent Family Chronicles, which followed a family through the history of the United States. He also wrote the North and South trilogy, centered on the Civil War, which was later made into a very popular television mini-series.

As I stated above, I have read a good deal of Leigh Brackett (1915-1978) recently, including a collection of tales featuring her most well-known hero, Eric John Stark, the novel Sword of Rhiannon, and from an anthology, the tale “Lorelei of the Red Mist.”

I have also covered the science fiction of Poul Anderson (1926-2001) before in this column, discussing his science-fictional heroes Captain Sir Dominic Flandry and Nicholas van Rijn, and you can find more biographic material in those earlier articles.

Adventurers Get No Respect

Adventure tales are sometimes looked down upon in science fiction fandom: Tales rooted in exciting exploits and driven by plot and action, like space opera and planetary romance, are often seen as somehow inferior to those centering on science (whether it be the hard sciences of the golden age, or the social sciences that take center stage in more recent fiction). The same thing happens in the fantasy world, where sword and sorcery tales are seen as a poorer cousin to the more serious stories labelled as high or epic fantasy. Science is important, as are weighty allegories and examinations of good and evil, but sometimes readers just want to have fun. And the publishing world is not a zero-sum game—especially now, when all manner of books and stories can appear in all sorts of formats and venues.

From the earliest days of the field, more serious tales, like those of H. G. Wells, appeared at the same time as less serious adventures in the pulp magazines, and neither detracted from the success of the other. People might dismiss adventure tales as escapism, or a waste of time, but one of the reasons they remain perennial favorites is that they are fun, and offer readers pure enjoyment. If I had one wish for the science fiction field, it would be that readers of all types of stories would be able to enjoy the tales they like best, without arguing their favorite styles are somehow superior. There is a time and place for every kind of story under the sun, and the existence of none of them invalidates the others. The world of science fiction should be a big tent, with room in it for all.

Swords Against Tomorrow

The longest story in the book, “Demon Journey” by Poul Anderson, comes first. It was originally published as “Witch of the Demon Seas” under the pseudonym A.A. Craig, in the magazine Planet Stories. The story takes place on a cloudy planet with plentiful seas, which might or might not be Venus. The captured hero is Corun, a captive of Khroman, ruler of Achaera. In his cell, Corun is approached by the sorcerer Shorzon and his witch daughter Chryseis, who has a dragonish pet called an ‘erinye.’ They know that Corun is one of the only people to visit the Xanthi, or Sea Demons, and returned to tell the tale. If he will lead them to the Sea Demons, they will give him his freedom.

Since the alternative is execution, he agrees, and they sail out on a galley crewed by blue-skinned Umlotuan cutthroats led by Captain Imazu. On the journey, despite his better judgement, Corun falls begins a romance with the beautiful Chryseis. Shorzun and Chryseis have an evil plan to conquer the world in partnership with the Sea Demons, and what follows is a twisty tale of plots and betrayals. The Sea Demons are fierce opponents, Shorzun is evil to the bone, and Chryseis appears not much better. But Captain Imazu and his crew are plucky companions, and Corun’s adventure ends more happily than might be expected. The story follows the Planet Stories template closely, but Anderson’s skill is apparent, and he delivers a taut little action-packed tale.

The next story, “Bazaar of the Bizarre” by Fritz Leiber, is the only one I had previously read, being an adventure of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. Like all their adventures, it is a delight. A new merchant’s shop has opened in Lankhmar, offering magical wares. The mysterious wizards Ningauble and Sheelba summon their two swordsmen, knowing the shop is a front for evil Devourers from another dimension. But the Gray Mouser has already been lured into the new shop, and so they must rely on the plucky Fafhrd to carry the day. They arm him with a Cloak of Invisibility and a Blindfold of True Seeing, and send him to battle.

Where the Mouser sees beautiful girls, riches, and treasures, Fafhrd sees only monsters and junk, and it will take all his swordsmanship to defeat the iron monster who appears to others as an eccentric shopkeeper, and rescue Mouser from being drawn into the other dimension. I enjoyed the action, the irony, and magic when I was young, but now find that the story also serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers and futility of unfettered capitalism.

“Vault of Silence” is a tale of magic and revenge from Lin Carter. The anthology’s only original story, it is pure sword and sorcery. Or rather, pure sorcery without the actual weaponry, since the hero Kellory is known as the “warrior who wore no sword.” We meet a young princess, Carthalla, who has been captured by brutal Thungoda barbarians. She is at the end of her rope, literally, tied to a horse and dragged behind her captors. Suddenly, a black-haired man, dressed in black, with a black wood staff (there’s a theme here) appears on the path, and forces them to stop. The barbarians attack him, only to be blasted by lightning emanating from his staff.

Buy the Book

Gideon the Ninth

The man in black, Kellory, calls Carthalla’s father and his advisors fools, and offers a hard truth, “Because they confuse that which they wish to be true with that which is true.” (Oh, if only all politicians heeded this warning.) It turns out that he is heir to a throne that is no more, a victim of those same Thungoda barbarians, and sworn to vengeance. Kellory is on a mission to find the ancient Book of Shadows and cannot be delayed, so the princess agrees to travel with him rather than be left alone on the road. He rescues her from a slimy monster and she aids him after an encounter with demons in an ancient citadel. A bond begins to grow between the two of them, and the only flaw in this tale is that it ends at this point, feeling more like a first chapter than a complete story.

The contribution from John Jakes, “Devils in the Walls,” is the first adventure of his character Brak the Barbarian, rewritten for this anthology. Brak is very much a pastiche of Robert E. Howard’s Conan, with the biggest difference being that Brak is a blond instead of a brunette. We find Brak captured and purchased as a slave by a mysterious woman, Mirande. She is the daughter of a man who was once the local lord, and wants him to venture into the demon-haunted ruins of her father’s palace to retrieve his treasure. They encounter a friar of the Nameless God on the road, whose symbol is a cross with arms of equal lengths. This encounter is fortunate, because when Brak enters the ruins, that mark of the cross is the only thing that saves him. At the end, after the greedy Mirande gets her just deserts, Brak and the friar ride out on the road together. While Christianity is never mentioned, it is clear that the Nameless God is an analogy for the Christian deity. While the tale is serviceably constructed, and enjoyable enough, I suspect many more will remember Jakes for his historical fiction than his tales of Brak.

The final story is an example of Leigh Brackett at her best: “Citadel of Lost Ships.” There are no swords in this tale; the closest we get is a man complaining that the loss of his sword hand has forced him to fight with a hook. The tale first appeared in Planet Stories, and is set in the consensus solar system used by many authors, in which every planet in habitable. This story, unlike Brackett’s other planet-bound stories, is also partially set in outer space. A hardened criminal, Roy Campbell, who escaped from the solar system’s Patrol, has crash-landed among a native tribe on Venus, the Kraylens. They have not only helped to heal his body, they’ve healed his soul, and for the first time in his life he has found peace.

When the authorities of the Coalition decide to take the Kraylen’s land, instead of accepting relocation into camps and cities, they decide to fight. Campbell, realizing that this will lead to their destruction, takes his repaired spaceship and heads for the Romany space station. Romany started with a collection of scrapped spaceships and castoff people, but grew until it was a potent force, the only organization in the solar system that can challenge the authorities and stand up for the little guy. Campbell is stunned when a disagreeable man, Tredrick, answers his hails, telling him the station will not help the Kraylens, and denies his docking request. But then someone else cuts in and gives him permission. It is a man, Marah (the one with the hook), and a woman, Stella. A civil war brewing on the station, and Tredrick is planning to betray the station to the Coalition in return for power.

Soon, Campbell is swept up in an effort not only to rescue the Kraylens, but also to preserve this last bastion of freedom in the solar system. There is even a bit of romance in the mix, between Campbell and Stella. The story is not only a great adventure tale, it is a story of redemption, and an indictment of colonialism and oppression (if it was a film, it would be perfect for a director like Frank Capra). Life has hardened Campbell into a human weapon, but in this case, he’s a weapon in service to a noble cause. Brackett is a master of packing remarkable amounts of worldbuilding into a story without ever burdening it with too much exposition, and the tale barrels along from beginning to end without a break in the action. This story alone was well worth the book’s price of admission, and I recently discovered you can now read it for free at Project Gutenberg.

Final Thoughts

This book is a quirky little collection, but turned out to be precisely what I was looking for: a group of well-told tales that were perfect for reading on a sunny summer afternoon. They were all enjoyable, with the standout being the Brackett tale, which I urge you all to take a few moments to read. There is a great economy to tales from Planet Stories, which always get right down to the action, and this story is a stellar example of pulp fiction at its finest.

And now, the floor is yours. Have you read this book, any of the stories it contains, or any other work by these authors? If so, what did you think of them? I would also welcome your thoughts on the place of adventure in science fiction—is it something you look down on or tend to gloss over, or is it something you actively seek out and enjoy?

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.