After re-reading the first couple of chapters of Poul Anderson’s The Man Who Counts, I grinned at the outrageous adventure story and said, “Man, they don’t write ’em like that anymore.”

Published in 1958, The Man Who Counts is now available as part of The Van Rijn Method: The Technic Civilization Saga #1. It features one of Anderson’s recurring heroes, the interstellar business tycoon Nicholas Van Rijn. Van Rijn is a throwback to the European Age of Exploration. He’s a fat, profane Dutch merchant, whose fine silk clothing is stained with snuff, who wears is his hair in oiled black ringlets, and who pledges in broken English to build a cathedral to his patron St. Dismas if only he can be relieved of having to suffer fools around him.

The novel opens as Van Rijn and his small party of human travelers have crash-landed on the planet Diomedes. Van Rijn and his helpless band find themselves in the midst of war between two stone-age nations, pitting the Drak’ho, a nation of Diomedes that live out their lives on vast, ocean-going rafts, against the Lannachska, who live on the land. Both nations can fly, they are winged aliens, and much of the charm of the novel comes from Anderson working out the details of life and war among people who can take to the air.

The Drak’ho seem destined to win this war, they’ve outgunned and outmatched the Lannachska in every way. And so of course Van Rijn takes the side of the underdog Lannachska, remaking their society and military to allow them to fight more effectively against the more powerful foe.

It’s a thrilling adventure story. Romance is provided by Wace, a middle manager in Van Rijn’s corporate empire, and Sandra, a genuine princess. Wace was born in a slum and worked his way out, Sandra is heir to the throne of a weakened planetary aristocracy, looking to revitalize the royal line with some new genetic input.

Van Rijn’s broken English and self-pitying monologues provide the humor. The old merchant likes to appear as a stupid old fool, the better to lull his opponents into complacency and outwit them. I particularly enjoyed a climactic sequence where Van Rijn goes into battle wearing leathery armor and wielding a tomahawk, bellowing the song “You Are My Sunshine” in German. (Or maybe it was Dutch.)

The Man Who Counts is the hardest of hard science fiction. In a foreword, Anderson describes how he went through the process of worldbuilding, first starting with a star, then figuring out the kinds of planets one might find around the star, then the ecology of those planets, and then the dominant species that might rise up. In the case of the Diomedans, their flying ability is a result of these calculations; no human-sized intelligent animal could fly on Earth, but because Diomedes has no metals, the planet is much lighter than Earth. It’s also bigger than Earth, which means it has the same surface gravity as our world, but with a deeper, thicker atmosphere, enabling large animals to fly.

Although the novel is more than 50 years old, it holds up quite well—amazing, considering it’s a hard science novel and science has changed a lot since then. I expect a biologist, astronomer, or astrophysicist might be able to punch some holes in the story, but it held up rock-solid to my educated-layman’s eye.

Often reading old genre fiction, the sexism prevalent at the time is painful today. But there’s none of that in The Man Who Counts. Gender roles of the Diomedes and the Earth humans are split along similar lines, but the novel presents this as a matter of culture, not because females are inferior. Sandra is every bit the princess, but that’s how she was raised, and she proves herself to be as tough, courageous, smart, and hard-working as any of the other characters.

Another area where these old novels are sometimes painful are in the depiction of ethnic minorities. Here, all the human characters are white people of European descent—but somehow it’s okay. There are no Asians, no Africans, just a bunch of white people running around on spaceships. But that’s the story Anderson wrote, and he approaches it with such verve and enthusiasm that you can’t be offended. His characters aren’t just Europeans—they’re Scandinavians, as though nobody else on Earth was important other than that small corner of Europe, and Anderson’s love for that culture is so infectious that we, as readers, can’t help but be charmed and delighted.

I mean, the hero of the novel is a burgher straight out of a Rembrandt painting. Although the novel says Van Rijn was born in Jakarta, he gives no indication of being anything other than a Renaissance Dutchman transplanted to a starship. That’s so ridiculous it’s wonderful. (Jakarta is the capital of Indonesia, which was colonized for three centuries by the Dutch.)

The politics of The Man Who Counts is more dated than the other elements, adding poignancy to the novel when it’s read here in the twenty-first century. Anderson wrote in the shadow of the end of World War II, and he’s unswervingly confident of the ability of business and commerce to uplift peoples and end wars, that nations that had been at war for dozens of generations would gladly put aside their conflict and become friends when they find it financially profitable to do so. I can understand how that appeared likely when The Man Who Counts was published, and our recent blood-enemies the Japanese and Germans were transforming into staunch allies with the benefit of American foreign aid and trade. A half-century later, with the Middle East torn apart by millennia of war that shows no sign of ending, and the Palestinians and Israelis choosing to be at each others’ throats again and again even when the road to peace is made clear for them, Anderson’s philosophy seems overly optimistic.

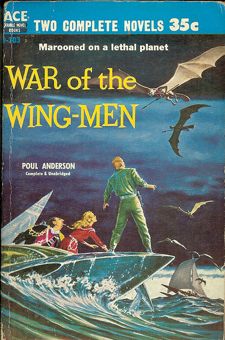

The Man Who Counts was initially published as a magazine serial. When it first came out as a book, the publisher titled it War of the Wing-Men. Anderson hated that title, and I understand why—but I find the silly, lurid old title charming.

When I started this post, I said that they don’t write books like The Man Who Counts anymore. The novel has speed and joyousness that seems lacking from much contemporary science fiction. So much contemporary SF seems to be a lot more serious, a lot more concerned with being respectable. But maybe I’m wrong here, maybe I’m just not reading the right novels.

Mitch Wagner used to be a journalist, became an Internet and social media marketer for a while, and is now doing journalism about Internet marketing, which makes him a little dizzy. He’s a fan with two novels in progress and a passel of stories, all unpublished. Follow him on Twitter or friend him on Facebook.