|

|

|

A Prisoner being paraded through the streets before his execution |

The last boyfriend I dated in China, before I left to attend graduate school in the US, was an army officer whose father was a general. One afternoon at work I received a distraught call from him asking to see me immediately. I met him in a park near the Seismological Bureau where I was working as an English interpreter. He arrived in his military jeep. When he stepped out, his face was stony and pale.

He told me that he had just returned from his first assignment as an officer in charge of an execution. He had been appointed to such a vital role because his father’s position ensured that he was from a trustworthy, truly revolutionary family.

The idea of people being executed was nothing new. I’d grown up seeing sheet after sheet of public notices pasted around the city. Always with the names of the executed criminals written in black ink, each marked with a red crossto signify their execution. I had also been required, along with the rest of my peers, to watch public trials and the parading of condemned prisoners through the streets before their execution. However, I never knew what happened on the execution grounds, and what he described below haunted me for years to come.

The young convict’s shaven head gleamed with sweat, mouth stuffed with dirty rags. The blindfold had fallen off, and his eyes focused on me, wide with fear. My firing squad stood before him. When the bullets struck, his head jerked up and he fell to the ground. Legs kicking, body twisting, he writhed in agony. He wasn’t dead, though not by accident. I had given an order to my men to shoot to wound.

As he drove me back to my Bureau, I saw an unsealed letter on his dashboard.

“What’s that?” I picked it up. It was addressed to a woman.

“A letter to the convict’s family. Well, actually a bill.”

“A bill for what?”

“The bullets we used on her son today.”

|

|

|

A Defendant without an attorney |

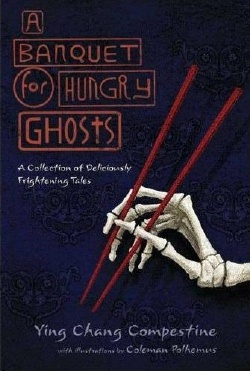

That wasn’t the worst of it. What he told me next about what happened to the nearly-dead prisoner, horrified me. I became obsessed with what occurred at the execution grounds. From then on, whenever I saw a public notice, I read it thoroughly and studied the convict’s face. Since I couldn’t discuss the subject openly with anyone, I spent a lot of time wondering; what kind of lives had these convicts led? What drove them to commit their crimes? Did they know what waited for them at the execution ground? While writing A Banquet for Hungry Ghosts, I pondered, how would ghosts that suffered as they did exact revenge?

|

|

|

|

Child beggars on city streets |

After I came to the US, I read every report I could find on the subject. This fixation became the basis for a story in Banquet. I chose to tell the tale from the convict’s point of view, because I wanted to give my readers a chance to experience his predicament. Let me stop here so I don’t spoil it.

|

|

Child beggars on city streets |

Like many writers who grew up under a repressive regime, I’ve learned to appreciate literature that doesn’t tackle the subject directly and thus impose the writer’s opinions on the readers. On the surface, A Banquet for Hungry Ghosts takes a light note, with stories named after tasty dishes and organized as a Chinese menu. But on a deeper level, the stories touch upon weighty subjects—brutality, cruelty, corruption, greed, and betrayal.

|

|

|

A monk counting money |

While I am very proud of the profound advances China has achieved in the last four decades, I am also troubled by the price that has been paid for this rapid progress—the rigged legal system, a widening gap between the rich and the poor, shady medical practices that exploit the working class, and corruption infiltrating every part facet of society.

My compulsion to write about these issues inspired many stories in Banquet like “Steamed Dumplings”, “Beef Stew”, “Tofu with Chili-Garlic Sauce”, and “Long Life Noodles.” The challenge I encountered while writing Banquet was not a lack of inspiration for the stories, or learning to write in a new genre, but in making peace with myself. Even some of my closest Chinese friends became very unhappy about me “airing China’s dirty laundry.” They urged me to write something more upbeat.

It took me months of soul-searching to reconfirm my belief—a writer has to write about what is significant to her. For China to continue forward, and earn the respect of other nations, it must be willing to air its dirty laundry, and address its problems openly. If honesty is the strongest expression of love, then Banquet is my love ballad to China.

It took me months of soul-searching to reconfirm my belief—a writer has to write about what is significant to her. For China to continue forward, and earn the respect of other nations, it must be willing to air its dirty laundry, and address its problems openly. If honesty is the strongest expression of love, then Banquet is my love ballad to China.

Ying writes ghost stories, novel, cookbooks, picture books, and hosts cooking shows. Her novel Revolution is not a Dinner Party has received twenty-eight awards, including the ALA Best Books and Notable Books. Ying has visited schools throughout the US and abroad, sharing with students her journey as a writer, how her life in China inspired her writing, and the challenges of writing in her second language. She has lectured on a variety of subjects at writer’s conferences and universities, and aboard cruise ships. Ying is available to talk about her books to book clubs in person, by telephone or online. Ying was born and raised in Wuhan, China. Her website is: www.yingc.com