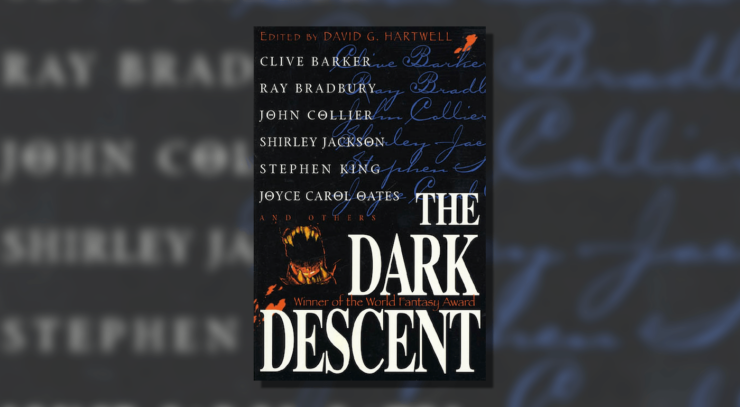

Welcome back to Dissecting The Dark Descent, where we lovingly delve into the guts of David Hartwell’s seminal 1987 anthology story by story, and in the process, explore the underpinnings of a genre we all love. For an in-depth introduction, here’s our intro post. I hope you enjoyed the first section of Descent and it’s lovely to have you all with me for almost a year of this column.

Manly Wade Wellman was an accomplished short horror author who, while his career spanned multiple genres, is perhaps best known for the genre he shared with his friend Karl Edward Wagner (whose work we previously discussed with “Sticks”), that gorgeous subset of American folk horror known as the “Appalachian Gothic.” Through Wellman’s tales of John the Balladeer (aka Silver John; or, if you know him from the 1970s movie, Hillbilly John), he put his own personal spin on the legends and culture of the people he felt closest to. “Vandy, Vandy” exemplifies those influences, playfully blending folk horror, Appalachian folk music, and American history into a tale of dark powers and good-hearted trickery worthy of any campfire. In the process, it uses the framework of the trickster myth to outline the triumph of the common people against the privileged, and poke fun at those who mythologize and enshrine their notions and beliefs about America without engaging with their actual history.

Deep in the Appalachian Mountains, a man named John happens upon a small gathering of musicians playing a folk tune called “Fire on the Mountain.” As he joins in on his silver-stringed guitar, he ingratiates himself with the musicians and asks if they might know a song he’s chasing called “Vandy, Vandy.” They point him to the Millens, a family further along the road who might know the tune. Upon arriving at the Millen home, John manages to learn part of the song, but the family’s performance is interrupted by a sinister warlock named Loden who clearly has designs on the Millens’ young daughter, Vandy. As John learns more about the song and its connection to the Millens, he must use every ounce of his cunning and occult knowledge to drive back Loden and free his new friends from the warlock’s clutches.

Beneath the surface of “Vandy, Vandy,” there’s an odd interplay of privileged nationalism against populism. Loden, the warlock lusting after Vandy, is a descendant of Salem witches and sees the man he calls “King Washington” as an ancient archnemesis. John even summons the heroic spirit of George Washington to dispatch Loden just as the warlock seems poised to triumph. It also shows in the divide between them, Loden being an old money, Old World type and John being a common mountain man (if a rather enigmatic one). Where Wellman’s story gets more complicated is that most of the weird nationalism comes from Loden. John’s conversation with the ten-year-old Calder Millen reveals that the unhinged mythology Loden spreads—a series of legends with a vague relation to the truth—is one with which John forcefully disagrees.

Loden draws his power from those legends, his distorted enmity of “King Washington,” and the dark magics taught by the Salem gramarie school. John turns those legends and folktales against Loden by the end of the story, using the warlock’s own conception of American legend to trap and destroy him. It’s not that the legends Loden weaves are true (he’s a 300-year-old pederast warlock who made a deal with dark powers to “turn good hearts bad”…so, not exactly the most trustworthy of characters), it’s that Loden believes in these legends and the idea of “his America” so hard it literally destroys him. It’s no different than any other individual, nostalgic for a version of America that never truly existed, trying to force their own restrictive interpretation of the past onto the rest of the country, to the detriment of all. Loden seeks to reshape reality to his benefit through his warped nationalism, but is ultimately destroyed by his own distorted version of history. His own occult magics backfire, and his fear of “King Washington” manifests as a heroic spirit that summarily dispatches Loden to whatever his just reward is, leaving the Millen family safe from his twisted machinations.

John, meanwhile, puts more of his interest in folk magic, existing culture, and (while still somewhat apocryphal) actual history. When Loden brings up his Salem heritage, John mentions how Cotton Mather killed twenty innocent women. When Calder asks him about Loden’s “King Washington,” John humors him but internally offers an aside that Washington was just a man who did great things and then passed on just like a mortal would—a human end for a human man. He uses his own magic, but “John from everywhere” (as he describes himself) is an average person who’s just uncannily clever. He doesn’t have the lineage and power Loden claims, he fits in with the people around him where Loden must bribe and cajole them, and he’s respectful to the Millens where Loden forces his presence upon them, making them uncomfortable with his attentions to Vandy. Even his victory over Loden comes out of understanding the spell Loden is casting and messing with it the only way he can, by distracting Loden with talk of how George Washington spurned Loden’s dark magics and won the war by human means, and tossing a quarter—a ward against dark magic bearing the face of Loden’s enemy—at Loden so the spell backfires.

As silly as the idea of “King Washington” striding out of the fireplace to break every bone in Loden’s body, thus saving our hero with a nod, reads to a modern audience, it’s also important to recognize that there’s an irony present in “Vandy, Vandy,” the same as in all good folktales. In most folktales, the trickster is never a figure in power, but instead turns the power and privilege of the villain against themselves. It’s not the actual Washington that strides forth from the fireplace, but the image of Washington that Loden conjured up in his own mind the moment John began taunting him. John even frees himself from Loden’s binding by using his memorization of the same spellbook Loden uses, successfully turning Loden’s power, privilege, petty grudges, and bizarre nationalism against him in a single move.

While it might not do everything perfectly, “Vandy, Vandy’s” mockery, playfulness, and trickster spirit do their best to build a more optimistic allegory than most Hartwell’s presented us. By taking the trickster myth and refashioning it into an American folk hero taking on a deranged occultist, Wellman’s Silver John shows that sometimes (not always, but sometimes), with the right knowledge, determination, and a little luck, you can undermine the privileged and predatory and cause their plans to backfire. Sometimes horror serves not just to reveal and give form to the terrors of our world, but to show us that those terrors cannot and will not always win—that the deck is stacked against us, but we can occasionally beat the odds.

Just like Silver John.

And now to turn it over to you: What was your first or your favorite Manly Wade Wellman story? (How hard is it not to always type that name in all-caps?)

Could Wellman have improved on his allegory? Did I let him off too easy?

And, as a supplemental question, have any of you seen The Legend of Hillbilly John? Is it any good?

Please join us in two weeks as we begin Part II of The Dark Descent, titled The Medusa in the Shield, as we pop by for another visit with strange story writer and professional ghost hunter Robert Aickman in “The Swords.”