I was four when Apollo 11 landed on the moon. I remember some things from when I was younger than that, so I find it hard to understand why I remember absolutely nothing about it. We did have a television, and though it only had one channel, I can’t believe BBC1 didn’t bother to mention it. We didn’t watch it often—people don’t believe me when I say I’ve never liked television—but it would also have been mentioned on the radio, which was constantly on. Somebody must have said to me “Jo, people have landed on the moon!” and I expect I reacted in some way, but I have absolutely no memory of this. I didn’t see any of the moon landings as they happened. But my family weren’t Luddite denialists. For as long as I can remember, I have known with a deep confidence that people have walked on the moon. They can put a man on the moon but they can’t make a windscreen wiper that doesn’t squeak?

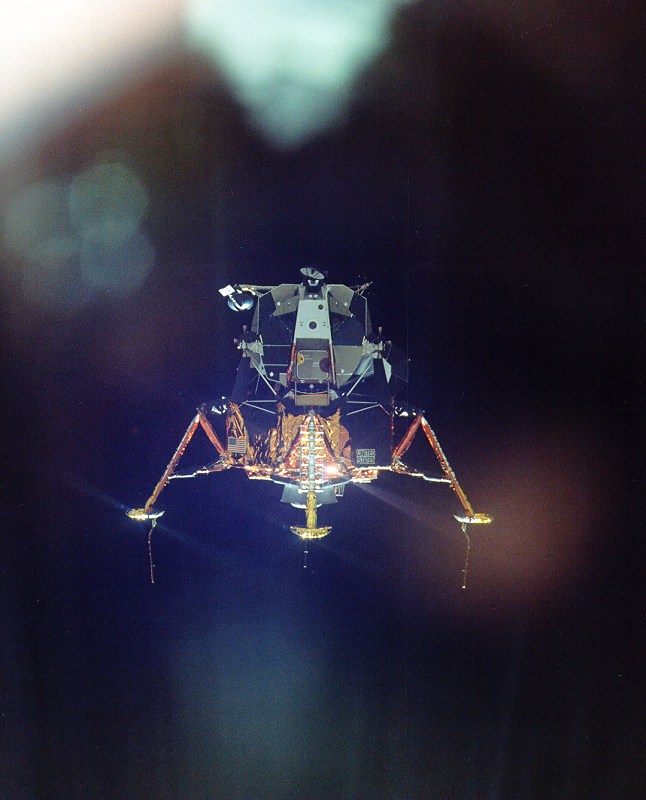

In the summer of 1977 when I read all of the SF in the library (in alphabetical order, Poul Anderson to Roger Zelazny) I read Heinlein’s “The Man Who Sold The Moon.” “The Man Who Sold The Moon” was written in 1951, eighteen years before Apollo 11. I understood this, but even so, even though I knew by the time I was twelve, and certainly by the time I was grown up, that the Apollo project had been a great series of government Five Year Plans and not a wildcat capitalist enterprise like D.D. Harriman’s moon voyage, I somehow didn’t entirely take in that the technology of Apollo was far behind the way Heinlein had imagined it. When I came to look at the historical Apollo programme, I was dumbstruck by what I call “pastshock” by analogy to Toffler’s “futureshock.” I couldn’t believe it had been so primitive, so limited, so narrowly goal-oriented. This wasn’t the moon landing science fiction had shown me! Where were the airlocks? They can put a man on the moon but they can’t make an airlock?

I was at an outdoor party once. There was a beautiful full moon sailing above the trees, above the whole planet. And there was a guy at the party who proclaimed loudly that the boots of the Apollo astronauts had contaminated the magic of the moon and that it should have been left untouched. I disagreed really strongly. I felt that the fact that people had visited the moon made it a real place, while not stopping it being beautiful. There it was, after all, shining silver, and the thought that people had been there, that I could potentially go there one day, made it better for me. That guy wanted it to be a fantasy moon, and I wanted it to be a science fiction moon. And that’s how the day of the moon landing affected me and my relationship with science fiction, twenty years after it happened. It gave me a science fiction moon, full of wonder and beauty and potentially within my grasp.

Jo Walton is a British-turned-Canadian science fiction and fantasy author, and the winner of the 2002 Campbell Award for Best New Writer. She is perhaps best known for her alternate history novel Farthing and its sequels, though her novel Tooth and Claw won the 2004 World Fantasy Award. She is also a regular blogger here at Tor.com.

Agree with the non-magic moon – It’s like Richard Feynman on science and its so-called inability to appreciate the beauty of flowers (or sunsets or the Moon):

“There are all kinds of interesting questions that come from a knowledge of science, which only adds to the excitement and mystery and awe of a flower. It only adds. I don’t understand how it subtracts.”

There had been one airlock in space by then, btw – the Russians had a rather inelegant collapsible/inflatable one for Leonov’s first spacewalk in 1965. db4

Nicholas: I’ve always agreed with Feynman, apart from the sexist language:

“What men are poets who can speak of Jupiter if he were a man, but if he is an immense spinning sphere of methane and ammonia must be silent?”

Though I should also note that Holst managed it splendidly in music.