In this monthly series reviewing classic science fiction books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of science fiction; books about soldiers and spacers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

Can one man stand against an entire planet? You might not think so, until you consider the fact that a tiny wasp can distract a driver and cause him to destroy his vehicle. Many works of fiction center on irregular warfare, as the subject offers myriad opportunities for tension and excitement, and I can’t think of any premise as engaging and entertaining as this one. In portraying many of the tactics of irregular warfare, however, the book also takes us into morally dubious territory—a fact made even more clear in the wake of recent events.

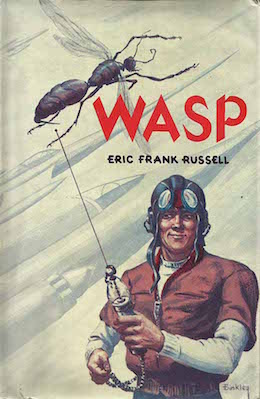

Wasp, written by Eric Frank Russell in 1958, is a classic from science fiction’s golden age. The novel demonstrates the type of havoc that a well-trained agent can unleash behind enemy lines, and illustrates the tactics of irregular warfare in a way that is informative as any textbook. Russell’s voice keeps the narrative interesting and exciting, and it stands as one of his best-remembered works.

About the Author

Eric Frank Russell (1905-1978) was the son of an instructor at the British Royal Military College at Sandhurst. In the late 1930s, he began contributing to American pulp science fiction magazines, most notably Astounding. One of his stories was featured in the first issue of Unknown, a magazine intended to serve as a fantasy companion to Astounding. He was a devotee of the works of Charles Fort, an American writer who was interested in the occult and mysterious phenomena, the paranormal, and secret conspiracies, and Fort’s theories influenced many of his tales. He wrote in very clean, crisp American-inflected prose that was often colored with a satirical tone. He became a favorite author of Astounding’s John Campbell, and his work frequently appeared in the magazine. He was a WWII veteran, but there are conflicting stories about the nature of his service—some sources claim he worked in communications for the RAF, but others say he worked in Military Intelligence. After the war, he became a prolific writer of science fiction in both short and long forms, and in 1955 his story “Allamagoosa” won the Hugo Award.

Eric Frank Russell (1905-1978) was the son of an instructor at the British Royal Military College at Sandhurst. In the late 1930s, he began contributing to American pulp science fiction magazines, most notably Astounding. One of his stories was featured in the first issue of Unknown, a magazine intended to serve as a fantasy companion to Astounding. He was a devotee of the works of Charles Fort, an American writer who was interested in the occult and mysterious phenomena, the paranormal, and secret conspiracies, and Fort’s theories influenced many of his tales. He wrote in very clean, crisp American-inflected prose that was often colored with a satirical tone. He became a favorite author of Astounding’s John Campbell, and his work frequently appeared in the magazine. He was a WWII veteran, but there are conflicting stories about the nature of his service—some sources claim he worked in communications for the RAF, but others say he worked in Military Intelligence. After the war, he became a prolific writer of science fiction in both short and long forms, and in 1955 his story “Allamagoosa” won the Hugo Award.

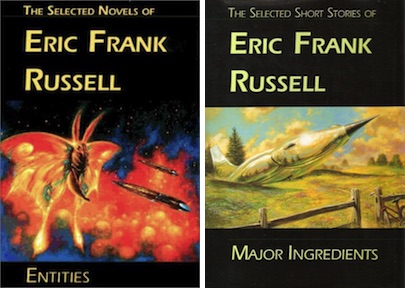

My own initial exposure to Russell consisted primarily of three works. The first was “Allamagoosa,” the story of a crew of a starship that falsifies an inventory report to try to hide a discrepancy, only to create problems far worse than any that would have resulted from an honest report. That story stuck with me, and during my own military career, I thought of it every time there was a choice between making an honest report that might lead to trouble, and a false one that might have obscured a problem. The second work was the story collection Men, Martians and Machines, which followed a ship with a crew of robots, humans, and Martians sent out to explore new (and often hostile) worlds. I probably read that one at too young an age, because some of the images of those hostile worlds stuck with me for years. And the third work is the subject of this essay: the espionage tale Wasp, which is probably Russell’s best known book. Wasp is a compelling story whose movie rights have been optioned twice, without ever being filmed. The first time was by Ringo Starr on behalf of the Beatles’ Apple Corps in 1970, and the second time by author Neil Gaiman in 2001. The NESFA press, in its efforts to keep older SF works available in collector’s editions, has published two volumes of Eric Frank Russell’s work, Entities (which contains Wasp, among other novels) and Major Ingredients (a collection including many of his short stories).

Wasp

The book opens with the protagonist, James Mowry, being called into the office of a government official named Wolf, who wants him to go behind the lines and impersonate a member of the Sirian Combine. The Sirians are at war with the Terrans, and things are not going well for humanity, which needs time to build up its forces and prevent them from being overwhelmed. Sirians are similar enough to humans that some minor plastic surgery and skin dyes can allow a human to impersonate them, and their level of technology is very close to that of the humans, as well. As someone who lived on a Sirian planet before the war, speaks the language, and has the right physique and temperament for independent duties, Mowry is asked to volunteer for training in irregular warfare, preparing him to infiltrate and disrupt the war effort, buying the time that Terra so desperately needs. After a short training course, Mowry is dropped into a wooded area on the planet Jaimec, where he establishes a base in a cave. He has printed materials purporting to be from a Sirian anti-war movement, significant amounts of counterfeit cash, a variety of identity papers, weapons, and explosives.

The book opens with the protagonist, James Mowry, being called into the office of a government official named Wolf, who wants him to go behind the lines and impersonate a member of the Sirian Combine. The Sirians are at war with the Terrans, and things are not going well for humanity, which needs time to build up its forces and prevent them from being overwhelmed. Sirians are similar enough to humans that some minor plastic surgery and skin dyes can allow a human to impersonate them, and their level of technology is very close to that of the humans, as well. As someone who lived on a Sirian planet before the war, speaks the language, and has the right physique and temperament for independent duties, Mowry is asked to volunteer for training in irregular warfare, preparing him to infiltrate and disrupt the war effort, buying the time that Terra so desperately needs. After a short training course, Mowry is dropped into a wooded area on the planet Jaimec, where he establishes a base in a cave. He has printed materials purporting to be from a Sirian anti-war movement, significant amounts of counterfeit cash, a variety of identity papers, weapons, and explosives.

His main opponents will be the Sirian secret police, the Kaitempi, an organization that is not above using brutal tactics to crush dissent. His own efforts will be focused on convincing the officials and population of the planet that the Dirac Angestun Gesept, or Sirian Freedom Party, is a real and viable organization (and not just a single man running a massive con game out of a cave). His first efforts consist of spreading rumors and distributing stickers around the city. On a trip to another city, Mowry runs into a Kaitempi Major, who he trails to his home and kills. The identification documents and other material he steals will become important to his future successes. He evades attempts by the authorities to capture him, and begins to see signs of his success in increased police activities. Mowry also makes contact with members of the criminal underground, who he hires to start assassinating officials listed on materials he took from the Major. He sends out threatening letters to government officials and organizations.

Mowry lies, manipulates, and deceives everyone he encounters. He begins to jump from identity to identity, and lodging to lodging, as the Kaitempi increases its efforts to neutralize the mythical D.A.G. He hires criminals to plant devices that will make the Sirians think their communications have been compromised; when one of his criminal associates is captures, he engineers a jailbreak that generates all sorts of chaos among local officials. While the Sirians continue to insist that the war effort is going well, Mowry is able to read between the lines and see the truth. When he’s told that invasion is imminent, he steps up his efforts, mailing explosive packages to various locations and planting explosive mines to destroy commercial shipping. By ramping up his efforts, however, the dangers also increase, and it is very likely that he will not survive to see the fruits of his labors.

Irregular Warfare

Irregular tactics have always been part of warfare, as opponents work to find and exploit any advantage over their foes. A newer term is “asymmetrical warfare,” which makes it clear that the goal is to apply your strengths to the enemy’s weaknesses. Instead of utilizing conventional military forces in order to attack similar competing forces, this type of strategy often involves personnel in disguise operating behind enemy lines. It is a tactic that favors offense, as the attacker gets to pick their targets, while the defender must apply efforts across the board. There were many irregular forces deployed during World War II, including Germany’s Brandenburg Division, the American Office of Strategic Services, and the British Special Air Service. Many of the tactics violate the Laws of War, and those caught engaging in irregular tactics can be subject to immediate execution. When tactics expand to include indiscriminate attacks, or deliberate attacks on the innocent and non-combatants, they cross the line into what we today call terrorism.

In his works on protracted warfare, Mao Zedong made it clear that irregular tactics cannot win the conflict, but they can disrupt the opponent’s efforts while building capabilities to challenge the enemy in a conventional conflict. And this is precisely the tactic Mowry’s handlers explain to him: the Terrans need breathing space to build up their strength, which the “wasps” can provide. We see Mowry walking through the various stages of irregular tactics, from disinformation to assassination and finally to indiscriminate attacks using package and letter bombs, and deliberate attacks on civilian shipping. By the time Mowry has moved on to tactics that violate basic moral principles as well as the established Laws of War, we have already grown to sympathize with him as a character—but it is clear he has completely crossed those lines by the end of the book.

A Whole New Perspective

Sometimes, you re-read a book and find things just the way you left them. Other times, you find surprises—and it’s not the book that has changed, it is your viewpoint that has changed. When I first read Wasp as a high school student, I think what attracted me to the story was that James Mowry was yet another example of an archetype often encouraged by John Campbell: the “competent man,” who might not fit in well with normal society, but who could be counted on to get the job done in whatever situation he finds himself. The plucky earthman, whose wits and determination could be counted on to prevail over even the most technologically advanced alien societies.

Sometimes, you re-read a book and find things just the way you left them. Other times, you find surprises—and it’s not the book that has changed, it is your viewpoint that has changed. When I first read Wasp as a high school student, I think what attracted me to the story was that James Mowry was yet another example of an archetype often encouraged by John Campbell: the “competent man,” who might not fit in well with normal society, but who could be counted on to get the job done in whatever situation he finds himself. The plucky earthman, whose wits and determination could be counted on to prevail over even the most technologically advanced alien societies.

Unsurprisingly, the book has not held up well in assuming a paper-based bureaucracy, and many of the tactics it portrays would be impossible in a computerized information-based society. The book also had a completely all-male cast of characters, not unusual for a war story in its day, but totally jarring today.

The information that Neil Gaiman liked the book enough to option its film rights also triggered a realization. As shown by the large roles that Loki and Anansi play in American Gods, Gaiman clearly has a soft spot in his heart for trickster archetypes, and I am sure this is one of the aspects of Wasp that appealed to me during my teen years—the idea of someone cleverer than those around him creating chaos, and turning adult society all topsy-turvy. Gaiman abandoned his efforts to write a script for the story after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, which leads me to my final point.

The biggest change in the years since the book was written is that, from a modern viewpoint, it is impossible for the reader not to sympathize with the Sirians. After all, we have recently seen international rivals attempt to disrupt elections with disinformation. We’ve also seen far too many indiscriminate attacks on civilians over the past few decades. No longer are the enemies portrayed in the book faceless opponents, alien and unsympathetic. Instead, they look and feel a lot like us. The moral ambiguity of the book now feels like a punch in the gut, and overshadows any admiration we might have for the cleverness of Mowry and the organization that trains and supports him. He might be fighting for “our” side, but does so in ways that make us deeply uncomfortable.

Final Thoughts

Eric Frank Russell is not a name that is instantly familiar to younger readers of science fiction today, but he was a major voice in the field during his heyday. His works were clever, witty, and thoughtful. If you haven’t read them, they are certainly worth a look.

And now, as always, I relinquish the floor to you. If you have read Wasp, what did you think of it? I’d also be interested to hear when you read it, and if that had an impact on your opinion of the work. Do the ends pursued by the “wasps” justify their means, in your opinion? And if you want to talk about any other works by Russell, I’d be glad to hear that as well.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for five decades, especially science fiction that deals with military matters, exploration and adventure. He is also a retired reserve officer with a background in military history and strategy