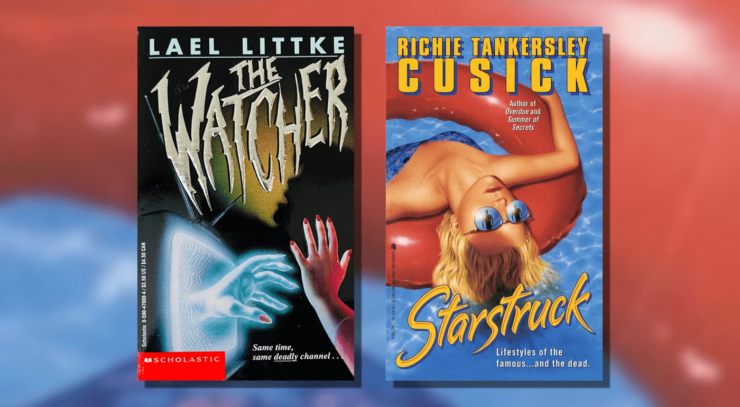

The teens of ‘90s horror usually keep pretty busy trying to solve dark mysteries and avoid murder attempts, but every now and then, they get the chance to put their feet up and watch a favorite television show or movie, hoping to take their minds off their troubles. But even the mindless entertainment of a soap opera or the latest action movie can open the door to further horrors, as the characters discover in Lael Littke’s The Watcher (1994) and Richie Tankersley Cusick’s Starstruck (1996). In both of these books, the boundaries between fiction and reality blur to the point of invisibility, as in The Watcher, Catherine Belmont loses track of the distinction between her own identity and that of her favorite soap opera character, Lost River’s Cassandra Bly,and in Starstruck, Miranda Peterson finds out the glamour of Hollywood isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

In The Watcher, Catherine Belmont’s obsession with Lost River is profound, overshadowing all other elements of her life. She runs from her high school to the local electronics store downtown to catch the latest episode of Lost River on the display televisions over her lunch break and she has modeled her wardrobe on the fashions of her favorite character, Cassandra. When a new guy in school comments on how much Catherine actually looks like Cassandra—a “dead ringer” (14), in fact, which is an ominous choice of words—Catherine has her hair cut to further emphasize this similarity. In uncertain situations, Catherine asks herself what Cassandra would do, adopting the fictional character’s speech patterns, body language, and mannerisms.

The lengths Catherine goes to in her attempts to emulate Cassandra are bizarre, for sure, but largely harmless and maybe even aspirational, a young woman trying on different identities and ways of being in the world as she works to figure out who she is. Things take a dangerous turn, however, when a mystery someone begins attacking Catherine in ways that mirror Cassandra’s plotline on Lost River: Cassandra’s car is tampered with and her seatbelt cut, she gets a threatening phone call, and the power is cut off to her house, with her attacker menacing Cassandra in the darkness. Similar events plague Catherine, with some minor variations: a cut seatbelt is left in front of her house; she gets the same threatening phone call, word-for-word; and when Catherine is in the auditorium for cheerleading practice after school one afternoon, the lights go out and someone torments her over the sound system. Catherine’s feelings about Lost River become a lot more complicated: on the one hand, it’s the last show she wants to watch, with its reminders of her own terrifying reality, but on the other hand, keeping up with Cassandra gives her a heads-up on what the next threat might look like.

There are several suspects, the strongest of which are Catherine’s neighbor Kade McGregor, the new boy Travis, and Britny Marsh. Kade and Catherine grew up together and Catherine views him as a brother, though he would clearly prefer something more intimate from their relationship. They live next door to each other and Kade spends an unsettling amount of time watching Catherine’s house, monitoring who’s coming and going. After Travis leaves one afternoon, Kade comes over to check on Catherine and make sure she’s okay, and when she assures him he really doesn’t need to do that, he tells her, “I like watching you, Cath” (145, emphasis original). This is creepy and made even more so when Catherine’s mother tells her about a boyfriend she had when she was Catherine’s age, Joe Sims, who “watched me … He was always watching me” (145, emphasis original), though that watching quickly escalated to murder when he grew jealous and shot T.J., another boy she was seeing. The plot thickens from there: T.J. is short for his full name, Travis Jalinsky, and he was the uncle of the new Travis who has just moved to town and become enamored with Catherine. With that new piece of information, Travis’s arrival in town and the quick friendship he has struck up with Catherine start to seem just a bit suspect. While the guys’ motivations could be possessiveness or revenge, with Britny, the cause for suspicion is jealousy and catty female competition, as Catherine assumes that Britny has her own romantic sights set on Travis and is still angry with Catherine about beating her out for the cheerleading team.

Somewhat unfortunately, none of these three are the culprit and Catherine’s real stalker is her supposed best friend, Liz, who just happens to be Joe Sims’ niece. After her uncle was institutionalized following T.J.’s murder, Liz’s mother similarly lost hold of reality. As Liz explains her skewed perspective of this cause-and-effect relationship, “His life was ruined, and hers, too. She got married and had me, but the marriage didn’t work out. She was too upset about her twin brother being locked up for the rest of his life. It made her sick, too. She’s in the same place he is now” (182). This is a flawed and potentially damaging representation of mental illness, particularly since Liz has followed the same dark path, with little awareness of or accountability for her actions.

Catherine may have lost herself in Lost River to some degree, but Liz turns to the soap opera as her playbook for what she should do next. When Cassandra is kidnapped on Lost River, Liz kidnaps Catherine, taking her to a cabin in the woods that belongs to Travis and Britny’s families, tying her up and waiting for the following day’s episode to find out what she should do next. She tells Catherine, “We’ll find out together … We’ll watch your soap opera and find out how Cassandra—and you—are going to die. The script is already written. There’s no way to change it” (185). There are plenty of flaws in this reasoning and Catherine points some of them out, including the fact that in reality, “They make changes to scripts all the time” (185), but Liz ignores all of them and carries on with her plan, only to be thwarted when in the next Lost River episode, Cassandra fights back against her kidnapper (who turns out to be one of her many ex-boyfriends, Dane). Liz is horrified, objecting “That’s not supposed to happen … No. No. No” (191). The two girls fight and Catherine is able to overpower and subdue Liz, just as the cavalry arrives, Travis and Kade coming to rescue, with clues provided by Britny’s astute analysis of that day’s Lost River episode, the cabin’s isolated location, and Travis’s missing keys.

In the closing pages, the tables seem to have turned, with the soap opera echoing art, rather than the other way around. In her final words to Catherine, Liz tells her friend “It’s still not over” (198), a line that is echoed a few minutes later word-for-word as the Lost River episode comes to a close. In soap operas and teen horror, the threat is never really bested and the danger can always return, but for now at least, Catherine seems to be (relatively) safe.

While life imitates art in The Watcher, in Cusick’s Starstruck, seventeen year old Miranda is offered a Hollywood dream when she wins a contest through On the Edge magazine to spend a week with megastar Byron Slater at his house in Los Angeles, and maybe even score a spot in his next movie. There are three winners, with these teenage girls competing against one another for Byron’s attention and affections, while being treated to fine food, shopping sprees with a personal stylist, and all kinds of social and publicity events.

There are a ton of red flags here: apparently these teens’ parents are somehow okay with sending unsupervised, underage girls to spend a week with a famous stranger. The possibilities for exploitation, abuse, and assault of these girls is almost limitless, both from Byron himself and from his cadre of hangers-on. Though there is a film role up for grabs, the screening process clearly isn’t going to be based on acting talent, since performance experience played no role in the selection of the finalists. After Byron and Miranda hit it off at their first meeting, he gives her a room in the main house, away from the guest house accommodations of the other contestants. The other so-called “responsible” adults aren’t much help either: when someone sends an incredibly revealing bikini to Miranda’s room, Lucille, Miranda’s chaperone from On the Edge, shrugs off her objections, saying “Oh, don’t be so shy. Remember, this is a fantasy trip. You can do things here you’d never do at home” (105, emphasis original). Miranda gives in, dons the bikini, and receives plenty of male attention, both from Byron and from his longtime friend and assistant, Nick Howard.

While there are already plenty of real-world dangers to worry about in this incredibly unsettling setup, no one really pays attention to those or bothers to address them at all, because they have bigger problems. Byron is certain that he is being stalked, with a crazy fan out to get him, though some members of his publicity team think he’s just mentally unstable, overreacting to a few weird phone calls, and could use a little break. Whether the truth is the threat of violence or an unpredictable superstar, it doesn’t seem like adding three complete strangers to the mix and intentionally amping up the drama with this competition is the way to go, but Byron’s publicity manager (and ex-girlfriend) Peg figures at least the spectacle will distract the paparazzi from whatever’s really going on.

There certainly does seem to be someone out to get Byron: the tiger from his private zoo is mysteriously released and nearly attacks Miranda and one of the other contestants (Miranda does, thankfully, scold Byron and she overtly questions the ethics of him having a private zoo in the first place). Someone tampers with his car, causing an accident that nearly kills Byron and Miranda. There are odd phone calls and threatening notes, which are signed “Starstruck.” When the girls are presented with corsages to wear when the group all goes out to dinner, Miranda’s corsage is replaced with a bloody heart and a note warning her that “Byron’s heart belongs to me” (178). Miranda hides the heart in her bathroom garbage can, because she wants to have a private conversation with Byron before disclosing this horror to the rest of the group, with legitimate threats to her own safety apparently not factoring into her thought processes,and they head out like nothing has happened. After their dinner, the group is surrounded by an out of control group of fans, an altercation that leaves Byron’s bodyguard Harley dead and Byron himself stabbed. No matter how dangerous and apparently straightforward these threats are, however, Peg continues to downplay their severity, dismissing them as unfortunate accidents and the tragic cost of fame, as she repeatedly insists that the show must go on, adhering strictly to the fun-filled schedule she has set for the contest winners … until the moment she turns up murdered in Miranda’s hot tub.

Despite all of these distractions, Miranda and Byron seem to hit it off, having long conversations in which he confesses his fears and vulnerabilities. While Miranda definitely has a crush on Byron, she remains refreshingly level-headed. When he flirts with her, she tells him “Don’t be a jerk. I’ll have a week here, and then I’ll fly home, and then I’ll never see you again. You’ll go on being a famous star and I’ll go on being a nobody who starts college in the fall. I don’t want any misunderstandings between us, Byron. No lies or promises or heartbreaks either” (126). While she may not trust him, Miranda and Byron build a sense of camaraderie in their time together, particularly because she is the only one who believes that he’s in danger.

But Byron is actually more dangerous than in danger. Miranda may not have fallen for his romantic lines, but she completely believes the story of his stalker, who it turns out doesn’t exist. As Nick explains to Miranda, “There never was a Starstruck. He did it for the publicity—so everyone would feel sorry for him and sympathetic—but Peg wouldn’t buy it! So he had to kill her to get her out of the way! And now you’ll be Starstruck’s last victim!” (216). If this is Byron’s plan, it’s not a great one: presumably, the police would want to find and arrest this murderous stalker, who doesn’t exist. How Byron will maintain his innocence while setting someone up to take the fall remains undetailed, but is bound to be tricky. It all goes back to the fickle nature of fame, with Nick telling Byron “You’re afraid you’re on your way down—that some new star will pass you by. This whole Starstruck thing was just a stunt to keep the media attention focused on you” (217). Byron is willing to sacrifice anything and anyone to maintain his star status. Miranda runs and nearly falls over the edge of a cliff (so many conveniently placed cliffs in these stories!), but is rescued by Nick, while Byron in his hot pursuit loses his footing and plunges over the edge to his death. Starstruck’s versions of the credits roll, with Miranda and Nick on a plane as Miranda heads back home, on the precipice of a new—and hopefully murder-free—romance.

In both The Watcher and Starstruck, there is a profound dissonance between fiction and reality, whether that fiction is the convoluted plot of Lost River or the mythos of celebrity. Both Catherine and Miranda are tempted to indulge in fantasy worlds—Catherine through her affinity with Cassandra, and Miranda in the week she spends at Byron’s home—and while they begin by believing that none of it is real, the dangerous breakdown between fantasy and reality puts their lives at risk. Those fictional worlds also elide very real threats, including stalking, jealousy, and manipulation, distracting Catherine and Miranda with exaggerated fictional dramas while the real dangers get ever closer. Those lives on-screen may fulfill these young women’s dreams, but they also hold their own nightmares, ones which Catherine and Miranda are lucky to escape from with their lives.