And so, it begins…

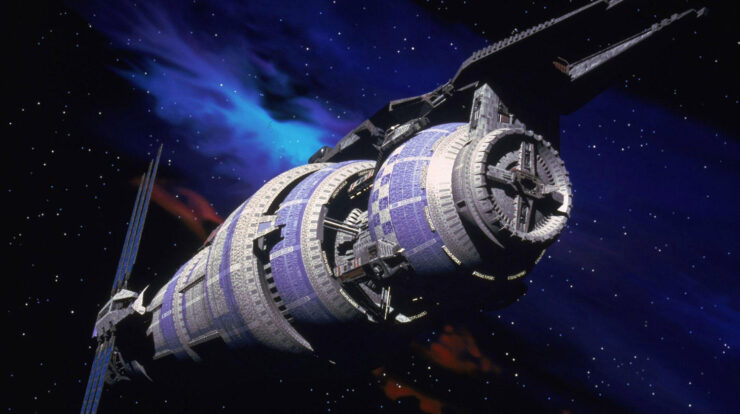

Or, in this case, restarts—that’s the theory, anyway, now that the WGA writer’s strike is in the rearview mirror, and progress can resume on so many projects, including J. Michael Straczynski’s long-promised attempt to reboot his classic sci-fi TV series, Babylon 5.

The reboot was first confirmed in 2021 by Straczynski on his Twitter account. Writing that the show was in development with the CW, Straczynski said:

As noted in the announcement, this is a reboot from the ground up rather than a continuation, for several reasons. Heraclitus wrote “You cannot step in the same river twice, for the river has changed, and you have changed.” In the years since B5, I’ve done a ton of other TV shows and movies, adding an equal number of tools to my toolbox, all of which I can bring to bear on one singular question: if I were creating Babylon 5 today, for the first time, knowing what I now know as a writer, what would it look like? How would it use all the storytelling tools and technological resources available in 2021 that were not on hand then? … So we will not be retelling the same story in the same way because of what Heraclitus said about the river. There would be no fun and no surprises.

From that detailed announcement, it’s apparent that the rebooted Babylon 5 will be quite different from its original iteration. I think it’s clear that this was always going to be the case, though—and not merely because of recasting and updates in special effects technology.

In its very bones, Babylon 5 was a unique experience. It was a bold attempt to experiment with the conventional format of TV, with a serialized storyline and continuity, unlike earlier shows like Star Trek or Quantum Leap or any number of other “story of the week” style science fiction programs. Here in our current era, post-prestige TV, that kind of storytelling is common, but in the 1990s, when Babylon 5 first entered pre-production, it was nearly unheard of.

Occasional radical programs like The Prisoner or Twin Peaks were the exception, not the norm, and in both of those cases, they were cancelled before they were able to tell complete stories. With Babylon 5, Straczynski set out with the deliberate intention to make a show that would last five seasons: No more, no less. It was a bold proposition… a dream given form, one might say.

It was also a massive exercise in planning, not just in terms of TV production, but in the writing and plotting of the show.

In fiction plotting, there are two broad schools of thought. One suggests that writers should allow themselves to permit characters and actions to come as they will—to “fly by the seat of one’s pants,” as it were. The “pantsers” are writers who don’t necessarily know where a story is heading, and are willing to adapt on the fly as ideas and character motivations evolve.

The second school of thought is that everything should be meticulously plotted. “Plotters” are writers who know precisely where the story is headed, and operate with a high degree of certainty as to how they’ll reach that conclusion.

Straczynski, at the start of Babylon 5, was unquestionably a plotter. Fans of the program will likely have heard about his penchant for building in “trap doors,” a term Straczynski used to refer to plot resolutions for main characters that branched off of the main story, should the need arise for recasting and the like.

In a forum post—which was one of his main tools for talking with fans at the time—Straczynski wrote about how these “trap doors” were a vital part of his writing process:

As a writer, doing a long-term story, it’d be dangerous and short-sighted for me to construct the story without trap doors for every single character… An actor can get hit by a meteor, walk off, whatever…That was one of the big risks going into a long-term storyline which I considered long in advance; you can’t predict real-world events, so you have to compensate for them and plan for them in advance. Otherwise you could paint yourself into a corner.

And of course, real-world events did impact the show. Michael O’Hare, who portrayed main character Commander Jeffrey Sinclair, began experiencing psychosis and paranoid delusions, including hallucinations. These issues, which Straczynski kept in confidence until after O’Hare’s passing in 2012, led to the creation of a new lead character, which was a disruption that Babylon 5 had not prepared for.

“I could write him out for a couple of episodes,” Straczynski said at a special “promise panel” (named for the promise he gave to O’Hare to keep his illness a secret until the actor’s death) before stunned attendees at Phoenix Comic Con in 2013, the first time he revealed the actor’s mental health issues publicly. “But I couldn’t write him out long enough to get the kind of help he really needed. I was prepared to shut down the show.”

O’Hare instead urged Straczynski to let him complete the first season, and afterwards agreed to part ways, save for a two-part appearance in the third season that tied off some loose plot threads and wrapped up Sinclair’s story arc.

From a narrative standpoint, it’s fascinating to consider how this particular challenge affected the trajectory of Babylon 5 on a profound level. Originally—as revealed in the single-spaced, seven-page synopsis that Straczynski parcels out through the 15-volume (14 plus a bonus volume) Babylon 5 script books—Sinclair was supposed to be the main character for the entire series’ run. As part of that run, Sinclair would not have become Valen, a prophet-like figure to a race called the Minbari, but would instead have fathered a “Minbari not born of Minbari,” as was prophesied by Valen in the distant past.

The mother of that child would have been Delenn, the Minbari ambassador to Babylon 5 who, at the end of the first season, undergoes a metamorphosis to become part human. Her purpose for doing so, as stated in the televised series, was to improve relations between humans and Minbari. In truth, the original motivation would have been to allow her body to be capable of bearing this prophesied child.

Indeed, in hindsight, this change does seem a little bit dubious without the pressing need to force prophecy, as it were. It also makes certain plot elements a bit clearer, such as the motivations of the Minbari assassin in the original pilot. Looking at that small arc through the lens of Sinclair as father to a half-Minbari child of prophecy, it becomes apparent that there would have been a faction of Minbari opposed to the very notion of mating with humans, and would treat a child of such a pairing as an abomination. Additionally, the “old Sinclair” shot we get in “Babylon Squared” that seems to show a potentially grim future is instead reduced to a somewhat flimsy retcon, as Sinclair is affected by the time dilation effect around Babylon 4. In the original plotline, it seems clear that the series meant to proceed into a potentially decades-long future, where the grown child of Sinclair and Delenn would meet his destiny.

Nevertheless, while Straczynski had meticulously plotted out his five-year arc, he also expressed a willingness to stray to the “pantser” side of the writing spectrum, as he mentioned in the same forum post where talked about his “trap door” escape plots:

As a writer, you have to be flexible enough to recognize a stronger, better path when it presents itself; to be so rigidly locked into your prior structure eliminates spontaneity and the chance to explore new routes.

Another unexpected speedbump in Babylon 5’s path came around the fourth season, as the now-apparently unstoppable show hit an immovable network. The Prime Time Entertainment Network, which aired the series, announced they would be shutting down, leaving Straczynski’s five-year plan, which had seemed much more solid after the end of the third season, in doubt.

As such, he felt obliged to produce a truncated version of his grand plot. The major threads of the Shadow War and the Earth Civil War were all wrapped up by Season 4’s conclusion. They even shot the finale, “Sleeping in Light,” but by the time Season 4 started to air, Babylon 5 had been suddenly saved by another network, TNT, and so that episode was ultimately shelved for the end of Season 5. Instead, Straczynski had the crew shoot “The Deconstruction of Falling Stars” to wrap up Season 4, and actor Claudia Christian, who by this point had departed the show amidst the confusion around Season 5, was absent.

Season 5 itself is sometimes maligned by fans as a strange coda to a completed story, but it nevertheless offers some incredible moments of deep emotional impact, particularly for series mainstays G’kar and Londo Mollari. In this respect, it’s worth noting that the “pantsing” side of writing, as Straczynski suggested, yielded some rewarding returns.

What makes Babylon 5 so singularly fascinating is that it managed, largely through the adaptability and force of will that Straczynski brought to the table as a writer and showrunner, to persevere in telling its story through a striking balance of “plotting” and “pantsing.”

Even in modern television, we still see the perils of trying to adapt or plan for long-running storylines. The Expanse, for instance, was cancelled twice. In the first instance, this led to a rapidly-paced third season that aimed to complete adaptations of the first three novels on which the show is based, and in the second instance, it led to an even-more-rapidly-paced sixth season, as Amazon shortened the episode order before axing the show.

Babylon 5 miraculously endured, and arguably thrived in spite of the various setbacks and challenges over the course of its run.

There are, of course, some elements which may have been stronger, had they survived the vagaries of production issues, cast departures, and so on. For instance, the original first officer of the station, Lieutenant Laurel Takashima, was intended to be the person who shot Garibaldi in the back at the end of season one, and who would have been implanted with the “control” personality that was instead given to telepath Talia Winters.

However, because that plot was given to Talia, it paved the way for the return of Lyta Alexander, who roared back into the show with a deeply badass background as a “doomsday telepath” enhanced by the enigmatic Vorlon race.

Then there are elements which maybe didn’t pack as much of a wallop. Catherine Sakai, Sinclair’s old flame who appears in a handful of episodes as a talented pilot and explorer, was clearly being set up to explore the ruins of Z’Ha’Dum—and everyone knows if you go there, you die. Her likely re-appearance after having her personality completely destroyed after being forced to serve the Shadows would have been harrowing, and would have been much more emotionally impactful than the Anna Sheridan plotline we got.

What this all adds up to is that Babylon 5 was, and remains, a fascinating early experiment in TV writing, and one that will never be repeated with the same results. It blazed a unique path, setting a standard for plotting a serialized story in a way that was revolutionary in television at the time, while allowing for Straczynski and his team of writers to fly by the seat of their pants when it became necessary, and because of that, it will inevitably change when it is rebooted.

But that is what makes it interesting, and endlessly exciting.