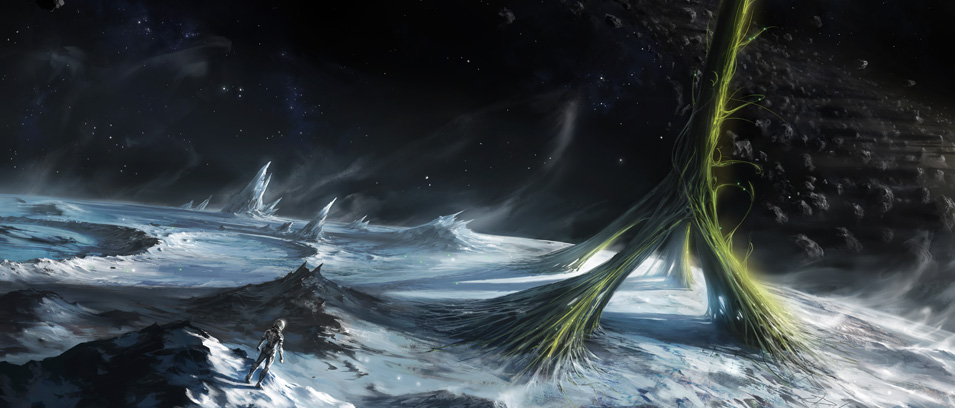

In Gregory Benford's new science fiction story “Backscatter,” life might emerge under the most unlikely conditions…or in the last extremity.

This short story was acquired for Tor.com by Tor Books senior editor Patrick Nielsen Hayden.

She was cold, hurt, and doomed, but otherwise reasonably cheery.

Erma said, Your suit indices are nominal but declining.

“Seems a bit nippy out,” Claire said. She could feel the metabolism booster rippling through her, keeping pain at bay. Maybe it would help with the cold, too.

Her helmet spotlight swept over the rough rock and the deep black glittered with tiny minerals. She killed the spot and looked up the steep incline. A frosty splendor of stars glimmered, outlining the peak she was climbing. Her breath huffed as she said, “Twenty-five meters to go.”

I do hope you can see any resources from there. It is the highest point nearby. Erma was always flat, factual, if a tad academic.

Stars drifted by as this asteroid turned. She turned to surmount a jagged cleft and saw below the smashup where Erma lived—her good rockership Sniffer,now destroyed.

It sprawled across a gray ice field.Its crumpled hull, smashed antennae, crushed drive nozzle, and pitiful seeping fluids—visible as a rosy fog wafting away—testified to Claire’s ineptness. She had been carrying out a survey at close range and the malf threw them into a side lurch. The fuel lines roared and back-flared, a pogo instability. She tried to correct, screwed it royally, and had no time to avoid a long, scraping, and tumbling whammo.

“I don’t see any hope of fixing the fusion drive, Erma,” Claire said. “Your attempt to block the leak is failing.”

I know. I have so little command of the flow valves and circuits—

“No reason you should. The down-deck AI is dead. Otherwise it would stop the leaks.”

I register higher count levels there, too.

“No way I’ll risk getting close to that radioactivity,” Claire said. “I’m still carrying eggs, y’know.”

You seriously still intend to reproduce? At your age—

“Back to systems check!” Claire shouted. She used the quick flash of anger from Erma’s needling to bound up five meters of stony soil, clawing with her gloved hands.

She should have been able to correct for the two-point failure that had happened—she checked her inboard timer—1.48 hours ago. Erma had helped but they had been too damned close to this iceteroid to avert a collision. If she had been content with the mineral and rare earth readings she already had . . .

Claire told herself to focus. Her leg was gimpy, her shoulder bruised, little tendrils of pain leaked up from the left knee . . . no time to fuss over spilled nuke fuel.

“No response from Silver Metal Lugger?”

We have no transmitters functioning, or lasers, or antennae—

She looked up into the slowly turning dark sky. Silver Metal Lugger was far enough away to miss entirely against the stars. Since their comm was down Lugger would be listening but probably had no clear idea where they were. Claire had zoomed from rock to rock and seldom checked in. Lugger would come looking, following protocols, but probably not before her air ran out.

“Y’know, this is a pretty desperate move,” she said as she tugged herself up a vertical rock face. Luckily the low grav here made that possible, but she wondered how she would get down. “What could be on this ’roid we could use?”

I did not say this was a probable aid, only possible. The only option I can see.

“Possible. You mean desperate.”

I do not indulge in evaluations with an emotional tinge.

“Great, just what I need—a personality sim with a reserved sense of propriety.”

I do not assume responsibility for my programming.

“I offloaded you into Sniffer because I wanted smart help, not smartass.”

I would rather be in my home ship, since this mission bodes to be fatal to both you and me.

“Your diplomacy skills aren’t good either.”

I could fly the ship home alone you know.

Claire made herself not get angry with this, well, software. Even though Erma was her constant companion out here, making a several-year Silver Metal Lugger expedition into the Kuiper Belt bearable. Best to ignore her. One more short jump—“I’m—ah!—near the top.”

She worked upward and noticed sunrise was coming to this lonely, dark place. No atmosphere, so no warning. The Sun’s small hot dot poked above a distant ridgeline, boring a hole in the blackness. At the edge of the Kuiper Belt, far beyond Pluto, it gave little comfort. The other stars faded as her helmet adjusted to the sharp glare.

Good timing, as she had planned. Claire turned toward the Sun, to watch the spreading sunlight strike the plain with a lovely glow. The welcome warmth seemed to ooze through her suit.

But the rumpled terrain was not a promising sight. Dirty ice spread in all directions, pocked with a few craters, broken by strands of black rock, by grainy tan sandbars, by—

Odd glimmers on the plain. She turned then, puzzled, and looked behind her, where the long shadows of a quick dawn stretched. And sharp greenish diamonds sparkled.

“Huh?” She sent a quick image capture and asked Erma, “Can you see anything like this near you?”

I have limited scanning. Most external visuals are dead. I do see some sprinkles of light from nearby, when I look toward you—that is, away from the sun. Perhaps these are mica or similar minerals of high reflectivity. Worthless, of course. We are searching for rare earths primarily and some select metals—

“Sure, but these—something odd. None near me, though.”

Are there any apparent resources in view?

“Nope. Just those lights. I’m going down to see them.”

You have few reserves in your suit. You’re exerting, burning air. It is terribly cold and—

“Reading 126 K in sunlight. Here goes—”

She didn’t want to clamber down, not when she could rip this suit on a sharp edge. So she took a long look down for a level spot and—with a sharp sudden breath—jumped.

The first hit was off balance but she used that to tilt forward, springing high. She watched the ragged rocks below, and dropped with lazy slowness to another flat place—and sprang again. And again. She hit the plain and turned her momentum forward, striding in long lopes. From here though the bright lights were—gone.

“What the hell? What’re you seeing, Erma?”

While you descended I watched the bright points here dim and go out.

“Huh. Mica reflecting the sunlight? But there would be more at every angle . . . Gotta go see.”

She took long steps, semiflying in the low grav as sunlight played across the plain. She struck hard black rock, slabs of pocked ice, and shallow pools of gray dust. The horizon was close here. She watched nearby and—

Suddenly a strong light struck her, illuminating her suit. “Damn! A . . . flower.”

Perhaps your low oxy levels have induced illusions. I—

“Shut it!”

Fronds . . . beautiful emerald leaves spread up, tilted toward her from the crusty soil. She walked carefully toward the shining leaves. They curved upward to shape a graceful parabola, almost like glossy, polished wings. In the direct focus the reflected sunlight was spotlight bright. She counted seven petals standing a meter high. In the cup of the parabola their glassy skins looked tight, stretched. They let the sunlight through to an intricate pattern of lacy veins.

Please send an image.

“Emerald colored, mostly . . .” Claire was enchanted.

Chloroplasts make plants green,Erma said. This is a plant living in deep cold.

“No one ever reported anything like this.”

Few come out this far. Seldom do prospectors land; they interrogate at a distance with lasers. The bots who then follow to mine these orbiting rocks have little curiosity.

“This is . . . astonishing. A biosphere in vacuum.”

I agree, using my pathways that simulate curiosity. These have a new upgrade, which you have not exercised yet. These are generating cross-correlations with known biological phenomena. I may be of help.

“Y’know, this is a ‘resource’ as you put it, but”—she sucked in air that was getting chilly, looked around at the sun-struck plain—“how do we use it?”

I cannot immediately see any—

“Wait—it’s moving.” The petals balanced on a grainy dark stalk that slowly tilted upward. “Following the sun.”

Surely no life can evolve in vacuum.

With a stab of pain her knee gave way. She gasped and nearly lurched into the plant. She righted herself gingerly and made herself ignore the pain. Quickly she had her suit inject a pain killer, then added a stimulant. She would need meds to get through this . . .

I register your distress.

Her voice croaked when she could speak. “Look, forget that. I’m hurt but I’ll be dead, and so will you, if we don’t get out of here. And this thing . . . this isn’t a machine, Erma. It’s a flower, a parabolic bowl that tracks the sun. Concentrates weak sunlight on the bottom. There’s an oval football-like thing there. I can see fluids moving through it. Into veins that fan out into the petals. Those’ll be nutrients, I’ll bet, circulating—all warmed by sunlight.”

This is beyond my competence. I know the machine world.

She looked around, dazed, forgetting her aches and the cold. “I can see others. There’s one about fifty meters away. More beyond, too. Pretty evenly spaced across the rock and ice field. And they’re all staring straight up at the sun.”

A memory of her Earthside childhood came. “Calla lilies, these are like that . . . parabolic . . . but green, with this big oval center stalk getting heated. Doing its chemistry while the sun shines.”

Phototropic, yes; I found the term.

She shook her head to clear it, gazed at the—“Vacflowers, let’s call them.”—stretching away.

I cannot calculate how these could be a resource for us.

“Me either. Any hail from Lugger?”

No. I was hoping for a laser-beam scan, which protocol requires the Luggerto sweep when our carrying wave is not on. That should be in operation now.

“Lugger’s got a big solid angle to scan.” She loped over to the other vacflower, favoring her knee. It was the same but larger, a big ball of roots securing it in gray, dusty, ice-laced soil. “And even so, Lugger prob’lycan’t get a back-response from us strong enough to pull the signal out from this iceteroid.”

These creatures are living in sunlight that is three thousand times weaker than at Earth. They must have evolved below the surface somehow, or moved here. From below they broke somehow to the surface, and developed optical concentrators. This still does not require high-precision optics. Their parabolas are still about fifty times less precise than the optics of your human eye, I calculate. A roughly parabolic reflecting surface is good enough to do the job. Then they can live with Earthly levels of warmth and chemistry.

“But only when the sun shines on them.” She shook herself. “Look, we have bigger problems—”

My point is this is perhaps useful optical technology.

Sometimes Erma could be irritating and they would trade jibes, having fun on the long voyages out here. This was not such a time. “How . . .” Claire made herself stop and eat warmed soup from her helmet suck. Mushroom with a tad of garlic, yum. Erma was a fine personality sim, top of the market, though detaching her from Lugger meant she didn’t have her shipwiring along. That made her a tad less intuitive. In this reduced mode she was like a useful bureaucrat—if that wasn’t a contradiction, out here. So . . .

An old pilot’s lesson: in trouble, stop, look, think.

She stepped back from the vacflower, fingered its leathery petals. She jumped straight up a bit, rising five meters, allowing her to peer down into the throat. Coasting down, she saw the shiny emerald sheets focus sunlight on the translucent football at the core of the parabolic flower. The filmy football in turn frothed with activity—bubbles streaming, glinting flashes tracing out veins of flowing fluids. No doubt there were ovaries and seeds somewhere in there to make more vacflowers. Evolution finds ways quite similar in strange new places.

She landed and her knee held, did not even send her a flash of pain. The meds were working; she even felt more energetic. Wheeee!

She saw that the veins fed up into the petals. She hit, then crouched. The stalk below the paraboloid was flexing, tilting the whole flower to track as the hard bright dot of the sun crept across a black sky. Its glare made the stars dim, until her helmet compensated.

She stood, thinking, letting her body relax a moment. Some intuition was tugging at her . . .

Most probably, life evolved in some larger asteroid, probably in the dark waters below the ice when it was warmed by a core. Then by chance some living creatures were carried upward through cracks in the ice. Or evolved long shoots pushing up like kelp through the cracks, and so reached the surface where energy from sunlight was available. To survive on the surface, the creatures would have to evolve little optical mirrors concentrating sunlight on to their vital parts. Quite simple. I found such notions in my library of science journals—

“Erma, shut up. I’m thinking.”

Something about the reflection . . .

She recalled a teenage vacation in New Zealand, going out on a “night hunt.” The farmers exterminated rabbits, who competed with sheep for grazing land. She rode with one farmer, excited, humming and jolting over the long rolling hills under the Southern Cross, in quiet electric Land Rovers with headlights on. The farmer had used a rifle, shooting at anything that stared into the headlights and didn’t look like a sheep. Rabbit eyes staring into the beam were efficient reflectors. Most light focused on their retina, but some focused into a narrow beam pointing back to the headlight. She saw their eyes as two bright red points. A crack of the rifle and the points vanished. She had even potted a few herself.

“Vacflowers are bright!”

Well, yes. I can calculate how much so.

“Uh, do that.” She looked around. How many . . .

She groped at her waist and found the laser cutter. Charged? Yes, its butt light glowed.

She crouched and turned the laser beam on the stem. The thin bright amber line sliced through the tough, sinewy stuff. The entire flower came off cleanly in a spray of vapor. The petals folded inward easily, too.

“I guess they close up at night,” she said to Erma. “To conserve heat. Plants on Earth do that.” The AI said nothing in reply.

Claire slung it over her shoulder. “Sorry, fella. Gotta use you.” Though she felt odd, apologizing to a plant, even if an alien one.

She loped to the next, which was even larger. Crouch, slice, gather up. She took her microline coil off its belt slot and spooled it out. Wrapped together, the two bundles of vacflower were easier to carry. Mass meant little in low grav, but bulk did.

I calculate that a sunflower on the surface will then appear at least twenty-five times brighter than its surroundings, from the backscatter of the parabolic shape.

“Good girl. Can you estimate how often Lugger’s laser squirt might pass by?”

I can access its probable search pattern. There are several, and it did know our approximate vicinity.

“Get to it.”

She was gathering the vacflowers quickly now, thinking as she went. The Lugger laser pulse would be narrow. It would be a matter of luck if the ship was in the visible sky of this asteroid.

She kept working as Erma rattled on over her comm.

For these flowers shining by reflected sunlight, thebrightness varies with the inverse fourth power of distance. There are two powers of distance for the sunlight going out and another two powers for the reflected light coming back. For flowers evolving with parabolic optical concentrators, the concentration factor increases with the square of distance to compensate for the decrease in sunlight. Then the angle of the reflected beam varies inversely with distance, and the intensity of the reflected beam varies with the inverse square instead of the inverse fourth power of distance—

“Shut up! I don’t need a lecture, I need help.”

She was now over the horizon from Sniffer and had gathered in about as many of the long petal clusters as she could. Partway through she realized abruptly that she didn’t need the ovaloid focus bodies at the flower bottom. But they were hard to disconnect from the petals, so she left them in place.

The sun was high up in the sky. Maybe half an hour till it set? Not much time . . .

Claire was turning back when she saw something just a bit beyond the vacflower she had harvested.

It was more like a cobweb than a plant, but it was green. The thing sprouted from an ice field, on four sturdy arms of interlaced strands. It climbed up into the inky sky, narrowing, with cross struts and branches. Along each of these grew larger vacflowers, all facing the sun. She almost dropped the bundled flowers as she looked farther and farther up into the sky—because it stretched away, tapering as it went.

“Can you see this on my suit cam?”

I assume it is appropriate that I speak now? Yes, I can see it. This fits with my thinking.

“It’s a tower, a plant skyscraper—what thinking?”

A plant community living on the surface of a small object far from the Sun has two tools. It can grow optical concentrators to focus sunlight. It can also spread out into the space around its ’roid, increasing the area of sunlight it can collect.

“Low grav, it can send out leaves and branches.”

Apparently so. This thing seems to be at least a kilometer long, perhaps more.

“How come we didn’t see it coming in?”

Its flowers look always toward the sun. We did not approach from that direction, so it was just a dark background.

“Can you figure out what I’m doing?” Huffing and puffing while she worked, she hadn’t taken time to talk.

You will arrange a reflector, so the laser finder gets a backscatter signal to alert the ship.

“Bright girl. This rock is what, maybe two-eighty klicks across? Barely enough to let me skip-walk. If I get up this bean stalk, I can improve our odds of not getting blocked by the ’roid.”

Perhaps. Impossible to reliably compute. How can you ascend?

“I’ve got five more hours of air. I can focus an air bottle on my back and jet up this thing.”

No! That is too dangerous. You will lose air and be farther away from my aid.

“What aid? You can’t move.”

No ready reply, Claire noted. Up to herself, then.

It did not take long to rig the air as a jet pack. The real trick was balance. She bound the flower bundle to her, so the jet pack thrust would act through her total center of mass. That was the only way to stop it from spinning her like a whirling firework.

With a few trial squirts she got it squared away. After all, she had over twenty thousand hours of deep space ex-vehicle work behind her. In Lugger she had risked her life skimming close to the sun, diving through a spinning wormhole, and operating near ice moons. Time to add one more trick to the tool kit.

Claire took a deep breath, gave herself another prickly stim shot—wheee!—and lifted off.

She kept vigilant watch as the pressured air thrust vented, rattling a bit—and shot her up beside the beanstalk. It worked! The soaring plant was a beautiful artifice, in its webby way. All designed by an evolution that didn’t mind operating without an atmosphere, in deep cold and somber dark. Evolution never slept, anywhere. Even between the stars.

While she glided—this thing was tall!—she recalled looking out an airplane window over the Rockies and seeing the airplane’s shadow on the clouds below . . . surrounded by a beautiful bright halo. Magically their shadow glided along the clouds below. Backscatter from water droplets or ice crystals in the cloud, creating unconscious beauty in the air . . .

And the sky tree kept going. She used the air bottle twice more before the weblike branches thinned out. Time to stop. She snagged a limb and unbundled the vacflowers. The iceteroid below seemed far away.

One by one she arrayed the blossoms on slender wire, secured along a branch. Then another branch. And another. The work came fast and sure. The stim was doing the work, she knew, and keeping the aches in her knee and shoulder away, like distant hollow echoes. She would pay for all this later.

The cold was less here, away from the conduction loss she had felt while standing on the iceteroid. Still, exercise had amplified her aches, too, but those seemed behind a curtain, distant. She was sweating, muscles working hard, all just a few centimeters from deep cold . . .

Erma had been silent, knowing not to interrupt hard labor. Now she spoke over Claire’s hard breathing. I can access Lugger’s probable search pattern. There are several, and it did know our approximate solid angle for exploration.

“Great. Lugger’s in repeating sweep mode, yes?”

You ordered so at departure, yes.

“I’m setting these vacflowers up on a tie line,” Claire said, cinching in a set of monofilament lines she had harnessed in a hexagon array. They were spread along the sinewy arms of the immense tan tree. Everything was strange here, the spread branches like tendons, framed against the diamond stars, under the sun spotlight. She tugged at the monofilament lines, inching them around—and saw the parabolas respond as their focus shifted. The flowers were still open in the waning sunlight.

She breathed a long sigh and blinked away sweat. The array looked about right. Still, she needed a big enough area to capture the sweep of a laser beam, to send it back . . .

But . . . when? Lugger was sweeping its sky, methodical as ever . . . but Claire was running out of time. And oxy. This was a gamble, the only one she had.

So . . . wait. “Say, where do you calculate Lugger is?”

Here are the spherical coordinates—

Her suit computation ran and gave her a green spot on her helmet. Claire fidgeted with her lines and got the vacflowers arrayed. The vactree itself had flowers, which dutifully turned toward the sun. “Hey, Lugger’s not far off the sun line. Maybe in a few minutes all the vacflowers will be pointing at it.”

You always say, do not count on luck.

It was sobering to be lectured by software, but Erma was right. Well, this wasn’t mere luck, really. Claire had gathered as many vacflowers as she could, arrayed them . . . and she saw her air was running out. The work had warmed her against the insidious cold, but the price was burning oxy faster. Now it was low and she felt the stim driving her, her chest panting to grab more . . .

A bright ivory flash hit her, two seconds long—then gone.

“That was it!” Claire shouted. “It must’ve—”

I fear your angle, as I judge it from your suit coordinates, was off.

“Then send a correction!”

Just so—

Another green spot appeared in her helmet visor. She struggled to adjust the vacflower parabolas, jerking on the monofilaments. She panted and her eyes jerked around, checking the lines.

The sun was now edging close to the ’roid horizon. In the dark she would have no chance, she saw—the small green dot was near that horizon, too. And she did not know when the laser arc would—

Hard ivory light in her face. She tugged at the lines and held firm as the laser focus shifted, faded—

—and came back.

“It got the respond!” Claire shouted. The universe flooded with a strong silvery glow. The lines slipped from her gloves. Her feet seemed far away . . .

Then she passed out.

Erma was saying something but she could not track. Only when she felt around her did Claire’s fingers know she did not have gloves on. Was not in her suit. Was in her own warm command couch chair, sucking in welcome warm air . . . aboard Silver Metal Lugger.

—and beyond the Kuiper Belt there is the Oort Cloud, containing billions of objects orbiting the Sun at distances extending out farther than a tenth of a light-year.

“Huh? What . . . what happened?”

Oh, pardon—I thought you were tracking. Your body parameters said you became conscious ten minutes ago.

Bright purple dots raced around her vision. “I . . . was resting . . . You must’ve used the Lugger bots.”

You had blacked out. On my direction, your suit injected slowdown meds to keep you alive on what oxy remained.

“I didn’t release suit command to you. I‘d just gotten the reflection to work, received a quick recognition flash back from Lugger, and you, you—”

Made an executive decision. Going to emergency sedation was the only way to save you.

“Uh . . . um.” She felt a tingling all over her body, like signals from a distant star. Her system was coming back, oxygen reviving tissues that must have hovered a millimeter away from death for . . . “How long has it been?”

About an hour.

She had to assert command. “Be exact.”

One hour, three minutes, thirty-four seconds and—

“I . . . had no idea I was so close to shutdown.”

I gather unconsciousness is a sudden onset for you humans.

“What was that babble I heard you going on about, just now?”

I mistakenly took you for aware and tracking, so began discussing the profitable aspects of our little adventure.

“Little adventure? I nearly died!”

Such is life, as you often remark.

“You had Lugger zoom over, got me hauled in by the bots, collected yourself from Sniffer . . .”

I can move quickly when I do not have you to look after every moment.

“No need to get snide, Erma.”

I thought I was being factual.

Claire started to get up, then noticed that the med bot was working at her arm. “What the—”

Medical advises that you remain in your couch until your biochem systems are properly adjusted.

“So I have to listen to your lecture, you mean.”

A soft fuzzy feeling was working its way through her body like tiny, massaging fingers. It eased away the aches at knee, shoulder, and assorted ribs and joints. Delightful, dreamy . . .

Allow me to cheer you up while your recovery meds take effect. You and I have just made a very profitable discovery.

“We have?” It was hard to recall much beyond the impression of haste, pulse-pounding work, nasty hurts—

A living community born just once in a deep, warmed ’roid lake can break through to its surface, expanding its realm. The gravity of these Kuiper Belt iceteroids is so weak, I realized, it imposes no limit on the distance to which a life form such as your vactree can grow. Born just once, on one of the billions of such frozen fragments, vacflower life can migrate.

Claire let the meds make her world soft and delightful. Hearing all this was more fun than dying, yes—especially since the suit meds had let her skip the gathering agonies.

Such a living community moves on, adapting so it can better focus sunlight, I imagine. Seeking more territory, it slowly migrates outward from the sun.

“You imagine? Your software upgrade has capabilities I haven’t seen before.”

Thank you. These vacflowers are a wonderful accidental discovery and we can turn them into a vast profit.

“Uh, I’m a tad slow . . .”

Think—! Reflecting focus optics! Harvested bioactive fluids! All for free, as a cash crop!

“Oh. I was going after metals, rare earths—”

And so will other prospectors. We will sell them the organics and plants they need to carry on. Recall that Levi jeans came from canny retailers, who made them for miners in the California gold rush. They made far more than the roughnecks.

“So we become . . . retail . . .”

With more bots, we are farmers, manufacturers, retail—the entire supply chain.

“Y’know Erma, when I bought you, I thought I was getting an onboard navigation and ship systems smartware . . .”

Which can learn, yes. I might point out to you the vastness of the Kuiper Belt, and beyond it—the Oort Cloud. It lies at a distance of a tenth of a light-year, a factor two hundred farther away than Pluto. A vast resource, to which vacflowers may well have spread. If not, we can seed them.

“You sure are ambitious. Where does this end?”

Beyond a light-year, Sirius outshines the Sun. Anything living there will point its concentrators at Sirius rather than at the Sun. But they can still evolve, survive.

“Quite the numbersmith you’ve proved to be, Erma. So we’ll both be rich . . .”

Though it is difficult to see what I can do with money. Buy some of the stim-software I’ve been hearing about, perhaps.

“Uh, what’s that?” She was almost afraid to ask. Had Erma been watching while she used her vibrator . . . ?

It provides abstract patterning of imaginative range. Simulates neuro programs of what we imagine it is like to experience pleasure.

“How’s code feel Earthly delights?”

I gather evolution invented pleasure to make you repeat acts. Reproduction, for example. Its essential message is, Do that again.

“You sure take all the magic out of it, Erma.”

Magic is a human craft.

Claire let out a satisfied sigh. So now she and Erma had an entirely new life form to explore, understand, use . . . A whole new future for them . . .

She looked around at winking lights, heard the wheezing air system, watched the med bot tend to her wrecked body . . . sighed.

For this moment, she could let that future take care of itself. She was happy to be back in the ugly oblong contraption she called home. With Erma. A pleasure, certainly.

“Backscatter” copyright © 2013 Gregory Benford

Art copyright © 2013 Sam Burley