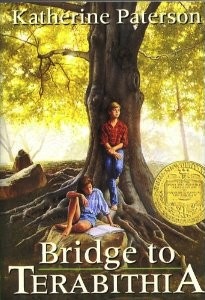

So. Bridge to Terabithia.

Are we all ready to start sobbing now? Like, hard?

Bridge to Terabithia has the dubious distinction of being one of the most frequently banned and/or challenged books in the United States, supposedly because of its references to witchcraft and atheism and a lot of swearing. I have another theory: it’s just so completely tragic and heartbreaking.

Also, when you are ten, the title just shrieks of false advertising.

Ok, before I go on, a confession: like many, I found my first reading of this book sad and tragic. In my case, though, it wasn’t the sudden and unexpected death, but because I had, foolishly enough, BELIEVED IN THE TITLE, which said, and I am just going to type this out again from lingering childhood resentment, Bridge to Terabithia, so I spent the entire book eagerly waiting for the characters to cross over to Terabithia and then to Narnia. The book even had an early scene where Jess finds himself bullied by his fellow students, somewhat like the first scene in The Silver Chair. But, (MAJOR SPOILER) THEY NEVER DID. FALSE ADVERTISING, Thomas Crowell Co (or now Harper Collins), FALSE ADVERTISING. I have never completely recovered.

Having said all that, Wikipedia and Katherine Paterson claim that Terabithia isn’t even exactly meant to be Narnia (thanks to Bridget McGovern for pointing this out), or the magical island Terebinthia mentioned in the Narnia books, even though Leslie keeps mentioning Narnia as she creates Terabithia thus creating a lot of confusion, like, THANKS LESLIE.

And now that I have that out of my system, moving on.

So, the story.

Bridge to Terabithia tells the story of the unlikely friendship between Jess and Leslie, two ten year olds living in a rural area not too far from Washington, DC. Jess belongs to a family with four girls and one boy. In a few well chosen sentences, Paterson establishes just how poor this family is: Jess has to share a room with his younger sisters; the walls are thin; the whole family has to pull together to buy one Barbie doll; his father is upset because he has a huge commute to a working class job that doesn’t even pay enough to buy decent Christmas presents; his older sisters are frustrated because they can’t have the same things their friends have; and the ongoing financial stress means has made his mother short tempered and irritable.

Jess is isolated for other reasons than money: he is generally inarticulate, not particularly good at school (and bored out of his mind in class), with only one gift: drawing. Desperate to prove himself to his family and friends, he decides to focus on running. It’s not a bad plan until the new girl who just moved in next door, Leslie, beats him in a race. Since she’s a girl, the other boys attempt to say this doesn’t count. Jess, to his credit, stands up for her, and slowly they become friends.

Leslie’s parents have decided to leave a comfortable home in the suburbs and instead head to a rural farm to figure out what’s important. In some ways it’s an admirable thought, but reading this as an adult I can’t help but think that they really should have checked out the school system first. Lark Creek Elementary is too short of money to even have adequate amounts of paper, let alone a cafeteria, athletic equipment, or sufficient desks. Classes are overcrowded. The school has managed to find a part time music teacher, Miss Edmunds, but the full time teachers are tired and overworked.

Leslie is completely different from anyone Jess has ever known. She is imaginative, well read, talented, and adventurous: she has a gift for words, and she goes scuba diving. She creates a fantasy world where she and Jess can play, and tells him stories. (Jess helps build their playhouse, which they reach via a swing rope.) She is almost fearless.

I say almost, since Leslie is scared of one thing: social interaction. She is not good at making friends or fitting in, and Jess knows this. Not only does he give her his friendship, but he also encourages her to reach out to abused child turned bully Janice Avery and May Belle. As her parents later note, Jess is one of the best things that ever happened to Leslie. They plot revenge against the school bullies, and for Christmas, they get each other the perfect gifts: Jess gets Leslie a puppy, and Leslie gets Jess watercolor paints.

Which does not mean that all goes smoothly. Jess is ten, and when his music teacher calls him to offer him a trip to visit the National Art Gallery and the Smithsonian, alone, he jumps for it without thinking much if at all. He does, after all, have a crush on her. (The teacher, not Leslie; one of the best parts of this book is that the friendship between Jess and Leslie is completely platonic.) Jess has also been struggling with how to tell Leslie that he’s terrified of her plans to swing over a flooding creek—he can’t swim—and this gets him out of that argument. He takes off without informing Leslie or his parents.

Incidentally, this is the one bit of the book that has not dated well at all: I cannot envision any teacher taking a ten year old student to the Smithsonian Museum for the day without at the very least speaking to parents these days, and, given concerns over child abuse, probably not even propose it in the first place unless the teacher was a very very long term friend of the parents or a relative. Miss Edmunds is neither. Sure, the trip is entirely benign in nature—Miss Edmunds has seen Jess’ art, and wants to nurture his talent—but Jess has a crush on her, so, still.

Not that this matters much, because when Jess returns, Leslie is dead.

This is both by far the best part of the book and the underlying reason, I suspect, why the book has so often been challenged. It’s incredibly, brutally, unfair. That’s part of the point, I know, but when you are a kid you have no indication that this is coming, and you are thrown. (Reading it through now as an adult I can see that Paterson did throw into small hints of what was coming, but I can assure you that I missed these hints completely when I was a kid.) Jess is even more thrown than kid readers: he is furious, and disbelieving, and even more furious and disbelieving that people want to tell him how to mourn—the same people that never appreciated Leslie when she was alive. He also feels incredibly guilty, thinking that if he had just invited Leslie to join him and the music teacher, she would never had crossed the flooding creek alone, and would still be alive. (That’s pretty debatable.) And even if not—well, he had still been wrong not to invite her. (That’s less debatable.)

This part is written with understanding and anger and grief; it’s beautifully done. And if I found myself wanting more scenes towards the end—Jess speaking with Janice Avery, Jess speaking with his music teacher—in a way, the absence of these scenes only strengthens the book. It’s incomplete and undone because sometimes life is like that. And the scene where Mrs. Myers tells Jess that when her husband died, she didn’t want to forget, telling Jess that it’s ok to grieve and to remember, is beautifully done and only strengthens this feeling: death is an unfinished thing.

The book has other beautifully done subtle touches: for instance, the way Paterson shows that Jess, like many ten year olds, seemingly hates his superficial older sisters—and yet, they band together with him to buy a Barbie doll for their younger sister, and Brenda is the one that can and does tell him straight out that Leslie is dead. It’s cruel, but it ends the suspense. Her later statement that Jess is not mourning enough (on the outside; he’s mourning a lot on the inside) shows that she is paying attention; she just has no idea how to talk to him. Which, again, is a part of mourning and grief. It’s just one of many little touches.

So, why the banning?

Well, in theory this is because of the book’s attitude towards witchcraft and religion, and the swearing. The witchcraft stuff can be dismissed easily enough—Jess and Leslie do talk about magic as they build their imaginary country of Terabithia, but only in the context of Let’s Pretend. The only real magic within the book, and this is arguable, happens at the end when Jess manages to describe Terabithia to May Belle to the point where she can almost see it, in her imagination, a sharing of an imaginary world that allows Jess to start healing. And that’s about it.

The religion argument has a bit more to it. Leslie’s parents are apparently atheists (or at least non-church goers; but Leslie states she has no need to believe.) Jess and Leslie have serious conversations about religion. Leslie has never been to church; Jess has, but has not thought much about it. His younger sister, May Belle, firmly believes that people who don’t read the Bible—like Leslie—are going straight to hell when they die, and starts to worry intensely about Leslie. (I am more inclined to believe Jess’ father who later firmly declares that God wouldn’t send little girls to hell.) But for those worried that the book preaches a message of secular humanism and atheism—well, I can’t help but notice that the kid who does go more or less irregularly to church and at least has a stated belief in the Bible, even if he doesn’t seem to know much about it or care much, is allowed to live. The non-believer dies. I would think the worry might be in the other direction.

The swearing seems pretty tame by today’s standards, although I can see some concern for younger readers. I suppose the book does, to a certain extent, encourage a retreat into a fantasy life for healing and play, but again, it also has a very strong message to be careful about this—following her fantasies is part of what gets Leslie killed.

Nonetheless, even the religion and the retreat into fantasy feel like surface issues. I think what people are really objecting to is a book that admits that sometimes kids die, and it doesn’t make any sense, and people do not necessarily deal well with it. In theory, children’s books are meant to be Good Places. Safe Places. Places where only Good Things Happen and where children don’t die for no reason at all and possibly go straight to hell. We want to protect children, even in books and in what they read.

This theory of course ignores a long standing history of often terrifying didactic literature, as well as multiple examples of angelic little children dying sweetly—hi, Beth from Little Women. Leslie breaks this mold in some ways: she’s certainly not angelic (her trick on Janice Avery is downright cruel), but she’s also not incurably evil. And she breaks the mold in another way: it’s not her death that transforms Jess. It’s her life.

It’s a real book. It’s a painful book. It’s a book where the kids don’t really get to go to their fantasy land. And so, it’s been banned. Even as some of us hope that in some reality, Leslie did get to go to Terabithia.

Banned Books Week 2013 is being celebrated from Sept. 22 to the 28; further information on Banned and Frequently Challenged Books is available from the American Library Association.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.