Mrs. Gilbert was one of those cool English teachers. You know the kind. She told us about wanting to go to Woodstock and not being allowed by her parents because she was too young. She taught us to enjoy Shakespeare by encouraging us to figure out all the filthy jokes in Romeo and Juliet—“the heads of the maids, or their maidenheads?” and “thou wilt fall backward when thou hast more wit!”—a surefire way to the hearts and minds of a bunch of ninth-grade honors students who fancied themselves to be filthy-minded. She’s the one who gave me an A on my Elric fanfiction when I had the temerity to hand it in for a writing assignment. And she’s the one who suggested that I read Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale.

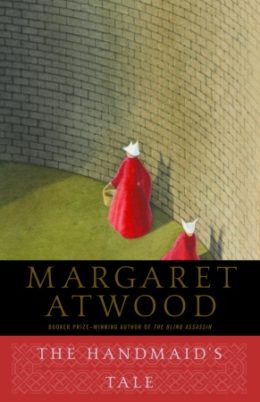

We had a strangely permissive library at our little high school, and far from being banned, Atwood’s novel was quite prominently placed amongst the As, the spine illustration of a woman in a red robe and white hat quite striking from across the room. Mrs. Gilbert, who knew me by then to be a dedicated SF&F fan with a nose for challenging books, said that I should read it; she thought I would find it very interesting.

That teens are drawn to dystopian fiction is news to absolutely no one, particularly here at Tor.com. Most of the regulars here have probably read Laura Miller’s analysis of dystopian novels as a parable of adolescence; if The Hunger Games and its like had been around in the late 1980s, I’d have devoured them whole. I’d already read Animal Farm and 1984 by that point, as well as Brave New World. I’d even made a cursory pass through Ayn Rand’s Anthem, which impressed me the least out of the lot. I actually learned the word dystopia from Margaret Atwood later that same year, when she came to lecture at Trinity University and talked about The Handmaid’s Tale and the history of utopian fiction.

But anyway, while the idea of an all-suppressive, totalitarian/authoritarian state wasn’t anything new, I knew very little about feminism at that point—certainly none of the history of the feminist movement, and little theory beyond a vague notion of “women’s lib,” a regrettable term that I remember being in currency well into the 1980s. And of sexual politics, abortion, pornography, and the like, I knew next to nothing apart from the fact that they were controversial. This was well before the internet, and when growing up and going to school in a relatively conservative environment, it was still possible, at fourteen, to be rather naive.

So The Handmaid’s Tale came as a bit of a shock.

At first glance it was easiest and most obvious to latch onto the themes of the systematic suppression and control of women’s sexuality, liberty, and reproductive ability, and to be horrified at a state that would deprive women of equal status under the law as a matter of principle. It took some time to untangle the deeper ideas at work, and to finally figure out that as with all good SF, The Handmaid’s Tale is not about the future; it’s about the now. Reading The Handmaid’s Tale at an impressionable age wasn’t like reading a contemporary YA dystopian novel; there was certainly nothing in it about navigating the seemingly arbitrary obstacles of adolescence. What it did prepare me for was the realization that even in our supposedly egalitarian society, a woman’s body and what she does (or doesn’t) with it are still an enormous source of controversy.

The dystopian novel functions in a manner similar to satire in that exaggeration is frequently its stock in trade; of course the Republic of Gilead is an extremist state, and while it certainly has its precedents in history (as Jo Walton has ably discussed here), the shock comes from seeing that kind of extremism laid out in what is recognizably a near-future Boston. Gilead’s social system literalizes and codifies the sexually-defined women’s roles that still inform gender relations even in these supposedly enlightened times: a woman is either a sex object (for procreation or pleasure, but not both), or she is a sexless nurturer. She is a Wife, a Handmaid, or a state-sanctioned prostitute, or she is a Martha or an Aunt. Atwood complicates the scenario still further by refusing to wax sentimental over bonds of sisterhood; amongst an oppressed class, siding with the oppressors is often the better survival choice, after all. In fact, women—particularly the Aunts—are the most fearsome police of other women’s behavior.

When Atwood gave her lecture at Trinity, she said that The Handmaid’s Tale was “a book about my ancestors”—the Puritans of New England. In this there’s a suggestion that the parallel urges to suppress and to comply are part of our cultural DNA. All it takes is a careful leveraging of fear to begin a slow dismantling of democracy as we know it. In the world of The Handmaid’s Tale, the catalyzing event is a mass assassination of the President and Congress—initially blamed on Islamic radicals, interestingly, though it’s suggested by the narrator that it was a false flag attack. And one of the first regressions of society is the systematic disenfranchisement of women.

Atwood wrote The Handmaid’s Tale in the mid-1980s, at the height of Reagan America, and it’s somewhat alarming to realize that the contemporary cultural forces underlying the novel haven’t really changed that much in the last thirty years. Then as now, suppression comes not so much in sweeping, slate-wiping gestures as in little erosions and aggressions—legislation that doesn’t ban abortion outright, but which makes it prohibitively difficult to get one; the way women don’t face bans on employment but do face constant, ingrained assumptions and subtle (or not so subtle) prejudice against their skills and abilities due to gender; the incredible hostility that so many women encounter online for voicing feminist opinions.

And The Handmaid’s Tale still has the power to chill and to shock; Atwood’s frank depictions of female sexuality—the suppression and abuse of it, as well as the desire and memory of desire that the narrator still cannot help but feel—still undoubtedly set off alarm bells amongst the self-appointed guardians of young minds. I hope there are still some Mrs. Gilberts out there, getting this book into the hands of the teenage girls—and boys—who need it.

Banned Books Week 2013 is being celebrated from Sept. 22 to the 28; further information on Banned and Frequently Challenged Books is available from the American Library Association.

Karin Kross lives and writes in Austin, TX. She’s pretty sure she lucked out with all her English teachers from eighth grade on. She can be found elsewhere on Tumblr and Twitter.