Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

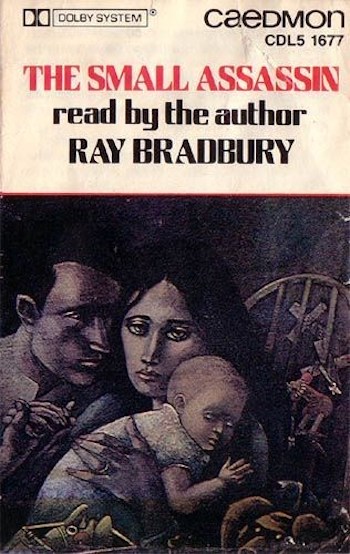

This week, we’re reading Ray Bradbury’s “The Small Assassin,” first published in the November 1946 issue of Dime Stories. Spoilers ahead. Trigger warning for harm to, and from, babies.

“I am dying and I can’t tell them now. They’d laugh…”

Summary

During the last month of her first pregnancy, Alice Leiber becomes convinced that she’s being murdered. Subtle signs, little suspicions, “things deep as sea tides in her,” make her believe her unborn child’s a killer. During an agonizing delivery, she’s convinced she’s dying under the very eyes of the doctors and nurses. They won’t blame the small assassin. No one will. They’ll “bury [her] in ignorance, mourn [her] and salvage [her] destroyer.”

When she wakes from anaesthesia, Dr. Jeffers and husband David are at her bedside. Alice pulls aside a coverlet to reveal her “murderer,” whom David proclaims “a fine baby!”

Jeffers privately tells David that Alice doesn’t like the baby. She was hysterical in the delivery room and said strange things. For a woman who’s suffered delivery trauma, it isn’t unusual to feel temporary distrust, to wish the baby was born dead. Alice will recover with plenty of love and tolerance on David’s part.

Driving home, David notices Alice holding the baby like a porcelain doll. She doesn’t want to name the boy until they “get an exceptional name for him.” At supper she avoids looking at the baby until David, exasperated, remarks you’d think a mother would take some interest in her child. Alice says not to talk that way in front of him. After David puts the baby to bed, she confides her conviction that the world is evil. Laws protect people, and their love for each other. The baby, though, knows nothing of laws or love. The two of them are horribly vulnerable

Buy the Book

Flyaway

Vulnerable to a helpless baby? David laughs, but Alice remains edgy, thinks she hears something in the library. David finds nothing. Upstairs they look in on the baby; his face is red and sweaty, he breathes hard and flails his hands. He must’ve been crying all alone, David says. He rolls the crib to their bedroom, where Alice reacts badly to learning that David can no longer put off a week-long business trip. It doesn’t help that their new cook will be there; Alice is uncomforted. It’s awful to be afraid of what she’s birthed, but she look how it watches from the crib. She cries herself to sleep in David’s arms. Then David notices “a sound of awareness and awakeness in the room”—the baby’s “small, moist, pinkly elastic lips” moving.

In the morning Alice appears better, and tells David to go on his trip—she’ll take care of the baby, all right.

The trip goes well until Dr. Jeffers recalls David: Alice is seriously ill with pneumonia. She was too good a mother, caring more for the baby than herself. But when David listens to Alice talk about how baby cried all night so she couldn’t sleep, he hears anger, fear and revulsion in her voice. Confession follows: Alice tried to smother the baby while David was gone, turning him on his face in the covers, but he righted himself and lay there smiling. There’s no love or protection between them, never will be.

Jeffers believes Alice is projecting her troubles on the baby. Things will get better if David keeps showing his love. Or, if not, Jeffers will find a psychiatrist. Things do improve over the summer, Alice seeming to overcome her fears. Then one midnight she wakes trembling, sure something’s watching them. David finds nothing. Baby cries, and David starts downstairs to get a bottle. At the top of the stairs he trips on baby’s ragdoll and barely manages to break his fall.

Next day, Alice isn’t as lucky. David returns home to find the ragdoll at the bottom of the stairs and Alice sprawled broken and dead. Upstairs the baby lies in his crib, red and sweaty, as if he’s been crying nonstop.

When Jeffers arrives, David says he’s decided to call the baby Lucifer. See, doc, Alice was right. Their baby’s an aberration, born thinking, born resentful at being pushed from the comfort and safety of the womb. He’s also more physically capable than other babies—enough to crawl around and spy and scheme to kill his parents. That’s why they’ve often found him red and breathless in the crib. Why, he probably tried to kill Alice during birth, with deft maneuvers to cause peritonitis!

Jeffers is horrified, but David persists: What does anyone know about “elemental little brains, warm with racial memory, hatred and raw cruelty, with no more thought than self-preservation,” entirely willing to get rid of a mother who knew too much. His baby boy. David wants to kill him.

Jeffers sedates David and leaves. Before slipping into unconsciousness, David hears something move in the hall…

Next morning Jeffers returns. No one answers his ring. Letting himself in, the doctor smells gas. He rushes to David’s bedroom, where a released jet billows the toxic stuff. David lies dead. He couldn’t have killed himself, Jeffers knows, for he was too heavily sedated.

He checks the nursery. The door’s closed, the crib empty. After the baby left, wind must have slammed the door, trapping it outside. It could be anywhere else, lurking. Yes, now he’s thinking crazy like Alice and David. But suddenly unsure of anything, Jeffers can’t take chances. He retrieves something from his medical bag and turns to a small rustle in the hall behind him. He operated to bring something into the world. Now he can operate to take it out.

What Jeffers brandishes gleams in the sunlight. “See, baby!” he says. “Something bright—something pretty!”

A scalpel.

What’s Cyclopean: The baby cries “like some small meteor dying in the vast inky gulf of space.”

The Degenerate Dutch: The way mothers normally talk about their kids is described as “a dollhouse world and the miniature life of that world.”

Mythos Making: The unnamed baby sits at the boundary between eldritch abomination (unknowable mind, generally displeased with the current state of the universe) and ghost haunting his own house (weird noises in the night, vanishing when the lights are turned on).

Libronomicon: Childcare books, preferably purchased from a store in Arkham or Dunwich, would be useful here.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Alice tells David he wouldn’t believe her fears if she explained them. She guesses she’s crazy.

Anne’s Commentary

I first read “The Small Assassin” back in fifth grade, which was not a good idea. I’d just embarked on my baby-sitting career, and loaded diapers were bad enough. Now I had to worry about dozing off while parents stayed out past their curfews, no doubt hoping Baby would accept a nice plump adolescent girl as a sacrifice in lieu of themselves. Was that the squelchy diaper-cushioned thud of Baby dropping from his crib? Was that his gurgling titter from behind the couch? Did that repeated metallic clink mean he was learning how to wield Mom’s sewing shears?

The worst thing that actually happened was that one toddler cleverly locked himself in his room so I couldn’t put him to bed. I had to jimmy open a window and crawl in to thwart the little darling.

Today, “Small Assassin” reminded me of two other works involving juvenile monsters. The first was Edward Gorey’s hilariously chilling “The Beastly Baby,” which begins “Once upon the time there was a baby. It was worse than other babies. For one thing, it was larger.” It had a beaky nose and mismatched hands, and it was usually damp and sticky from incessant self-pitying weeping, and it amused itself with such droll pranks as decapitating the family cat. Eventually an eagle carried it off the edge of a cliff on which the parents had (with desperate hope) deposited it. Oops, the eagle dropped Baby, and there followed a particularly nasty splat. A happier ending than the Leibers’. I guess Alice didn’t think of exposing little Lucifer to hungry raptors, or maybe there weren’t many in her cozy suburban neighborhood.

The second work was Stephen King’s Pet Sematary, perhaps the novel of his that has scared me most deeply, though it has tough competition. Its evil-toddler Gage (heart-breakingly sympathetic given the circumstances of his evilification) gets into physician Dad’s medical bag and secures a—scalpel. Uh oh, and he wields it as expertly as Dr. Jeffers will, we presume. Doc Dad will have to make do with a syringe loaded with deadly chemicals. Huh, why didn’t Dr. Jeffers think of that? Much neater than his idea of operating Lucifer to death. But best would have been for Jeffers to gas Lucifer, right? Yeah, give the little monster a dose of his own medicine while simultaneously gaining a great cover story for the police. Officers, I found father and son together in the gas-filled room—obviously poor David Leiber was maddened by Alice’s death and so took both their lives.

Always provide yourself with a good cover story when dispatching monsters. The authorities are generally lacking in imagination and senses of irony. I doubt they’ll buy any claim that Lucifer was a bad seed needing instant extermination, even from a (formerly) respected obstetrician.

I have another problem with the gas—how does little Lucifer know how to use it as a murder weapon? Surely the hazards of heating fuel are not part of the “racial memory” he’s inherited? Or did he kind of download Alice’s knowledge of modern technology while in the womb? And why am I worrying at this detail when the whole notion of a birth-phobic super-mastermind super-athletic inherently-evil baby is outlandish?

It’s because when the BIG IDEA is outlandish, all the SMALL DETAILS that surround it had better not be. Details create verisimilitude and foster reader credulity. Sounder, perhaps, is David’s thought that a malicious fetus could maneuver to create internal distress—say, peritonitis—for Mom.

Oh no, now I’m flashing back to the 1974 movie It’s Alive. Its mutant-killer newborn scared me so much I couldn’t even watch the TV ads for this film, which featured a sweet bassinet that slowly rotates to reveal—a dangling hideously clawed baby hand! And turns out the claws were among this infant’s cutest features. At least Lucifer Leiber was a fine (looking) baby and didn’t go around leaping like the rabbit from Monty Python and the Holy Grail to tear out the throats of overconfident cops.

Give him (and Bradbury) that, Lucifer’s a subtler murderer. A subtle mutant, too. His only giveaway feature seems to be his unusually intent blue stare. It’s in the eyes, people. Bixby’s Anthony has those intent purple eyes. Even Atherton’s angel-child Blanche can unnerve with the beauty of mind and/or unspeakable melancholy of her dark blue eyes. I guess Jackson’s little Johnny has normal enough eyes, but then Jackson’s all about the potential beastliness of the ordinary.

Bradbury’s also about how closely the mundane and terrible co-exist. And so is King, and Lovecraft, too. This is the root or core of horror, then? An idea Bradbury expresses gorgeously in a “Small Assassin” passage that would have resonated with Howard: Alice thinks of “a perfectly calm stretch of tropic water,” of “wanting to bathe in it and finding, just as the tide takes your body, that monsters dwell just under the surface, things unseen, bloated, many-armed, sharp-finned, malignant and inescapable.”

Babies are Deep Ones? Now there’s a fine closing thought.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

There are well-written stories and poorly written stories. There are stories that successfully invoke fear, creep me out, make me shiver when I pass a window, or make me question comforts I’ve taken for granted. And then, sometimes, there’s a story that hits all my buttons in a bad way and just grosses me out. This, dear readers, is that story. It’s well-written, legitimately creepy, and I hate it.

I’ve mentioned before that I’m not rational about stories of parenthood. This doesn’t seem to extend to all scary-children stories—I wouldn’t blame anyone who successfully knocked Anthony over the head, and suspect little Johnny would benefit from a Miskatonic-trained therapist. But show me parents who could do better, without actually acknowledging how much better they could do, and it makes me extremely grumpy.

Never mind that several characters here are doing remarkably well for 1946. A dad who just takes over childcare when mom can’t handle it is an all-too-rare blessing in the 21st century; David Leiber impressed the hell out of me. Jeffers may take David’s fears far more seriously than Alice’s, and be remarkably blasé about attempted infanticide, but he’s still sympathetic to Alice’s fears at a time when “cold” mothers were blamed for just about everything.

But… I have questions. Exasperated questions. Like: Where does this smart, resentful child think food will come from when Mommy is dead? Why does a family that can afford servants (full-time or part-time depending on the paragraph) not get a nanny to fill in for the absent maternal love—something that well-to-do families have outsourced for centuries on far less provocation? Who does take care of the baby during the days when pneumonia-ridden Alice refuses to touch him? Who does Jeffers think is going to take care of the baby when he gives David a 15-hour sedative?

I can’t help but suspect that this story would have been very different a few years later, after Bradbury married and had kids himself. Even where the Leibers’ kid is genuinely disturbing, I don’t sense any gut-level experience with parental exhaustion, or resonance with the genuine moments of fear and resentment that can happen when you’re trying to get a baby to finally. Fall. Asleep. Bradbury’s not completely off-base—I get the distinct impression that he had actually met babies and exhausted mothers rather than merely reading second-hand accounts—but I do wonder what his wife Marguerite (married 1947) had to say about the story (published 1946.

I also can’t help but suspect that the Leibers would benefit from a support group, or possibly an adoption arrangement, with Gina from “Special Needs Child.” Gina’s denial may have irritated me almost as much as the current story, but give her a cognitively precocious kid and she’d… probably still be in denial, but at least love the kid enough to reassure them that they aren’t in danger. Better than Gina, though, would be an open-minded child psychologist and an enrichment program—as opposed to a family doctor riffing on Freud. (A time-traveler with some knowledge of post-partum depression would help, too.)

Suppose one child in a billion is magically able to crawl and think murderous baby thoughts? Kids are selfish, sure, but as long as the kid isn’t inconveniently omnipotent, there are things you can do about that.

Enough with the terrifying children. Maybe it’s time to curl up with a comforting copy of the latest Weird Tales instead, or a few pages from the Necronomicon—join us next week for Manly Wade Welman’s “The Terrible Parchment.” You can find it in The Second Cthulhu Mythos Megapack.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is now available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.