The decision to remake a film that’s barely two years old and has already received critical acclaim in America—implying that it had a good deal of play here—is an odd one. Remakes have a tendency to use older films, or movies that weren’t popular outside of their original country, or stories that live to be told again and again, like Shakespeare. Using a new, popular film for inspiration instead invites the question: why is this even necessary? The newest version has to justify its existence in a way that remakes of older movies generally don’t. (Which isn’t to say they never do—for example, the remake of The Day the Earth Stood Still. That movie certainly had to try to justify itself.)

The best answer to the question of “why” is that the new film wants to go further into the textual source material of the novel than the original, that it wants to further explore and expound upon themes. That’s a pretty damn good reason to go for a remake.

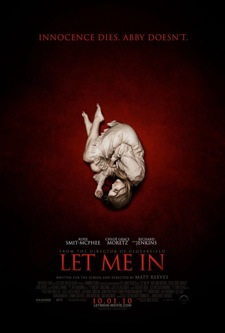

Let Me In does the exact opposite. Instead of going further and doing more, the film backs off of anything remotely challenging or “icky” for the average film-goer and rips out the original thematic structure to replace it with a predictable moral quandary. Which isn’t to say that it was a bad film on its own—but it cannot exist on its own in the critical field because it follows so very closely on the heels of its still-talked-about, still-popular inspiration. (On the other hand, as I’ll discuss below, it wasn’t a particularly well structured movie on its own, either.)

I will very briefly get on my soapbox about the thing that made me the most irritated about Let Me In: the decision to erase the issues of gender and sexuality from the film. Abby is biologically female and identifies as female. There’s no real middle ground available to her in the remake. Eli, in Let the Right One In and the text, is not biologically female and, despite appearances, does not actually seem to identify as female, either. There are complex layers of commentary about performative gender and convenient socialization in Let the Right One In, especially considering that Oskar doesn’t quite care at all that his soul-mate is not biologically female. (Really, once the vampire thing is out of the way, there’s nothing much more shocking than that, and he handles that well.) The decision to wipe those issues completely from the movie—including Oskar’s father—was one I can at my most forgiving call cowardly. It’s the idea that American audiences are too prejudiced and too queer-phobic to deal with those topics in a movie. Admittedly, that’s probably correct, but it was still caving in on an issue that the director had the opportunity to work with. Hell, he could have chosen to make it even more obvious and actually deal with the questions of sexuality! Instead, he retreats to a comfortable hetero-normative position.

End soapbox, continue with content-review.

The word I would use to describe Let the Right One In is “quiet,” or perhaps “poignant.” The word I would use to describe Let Me In is “clumsy,” maybe even (and this is cheating) “trying too hard.”

What made the original film so engaging is that it’s not a horror movie, it’s a macabre and socially aware romance. It’s a story about two immeasurably damaged young people—even though one isn’t really young at all—finding each other and connecting precisely because of their strangeness and socially unacceptable behavior. Their deep connection and the outlet it provides them both is both sweet and frightening. Oskar and Eli are both well on their way to being “monsters” and are not redeemed from it. In fact, the audience is made to sympathize greatly with them at the same time as feeling intense discomfort.

Let Me In summarily abandons that—somehow, the main thematic freight of the original wasn’t satisfying enough.

Examining the characterization of Oskar versus Owen makes this point abundantly clear. Oskar is a severely socially inadequate person. (I refuse to call him a child, because Oskar is no more a child than Eli.) He’s developed as a sort of proto-serial-killer: he has a special scrapbook of gruesome delights, he fantasizes constantly about using his rather large knife to hurt other people, he’s unable to make social connections with even his perfectly normal and interested parents. His posture and self-affect are removed, he doesn’t understand basic conversation and doesn’t behave in any way like a normal person of his age. He’s frankly a bit creepy when you put thought into it.

Eli says to him in conversation at one point that he wants to kill people—Eli just does it because it’s necessary, for survival. Oskar is the perfect match for Eli precisely because of this. He’s never turned off by or even particularly concerned by the violence or death that seems to follow in Eli’s wake. It just doesn’t bother him, any more than her status as boy/girl or vampire/human. Not only that, I would argue that especially in the pool-scene at the end, Eli’s capability for violence pleases him and he feels properly revenged thanks to her. (Using the “she” pronoun for convenience.)

Owen on the other hand is a relatively normal kid. He’s constantly singing, goofing off, reacting to his parents like a predictable twelve-year-old including outbursts like “god, mom!” I winced more about Owen’s characterization than anything else, to be perfectly honest. The most creepy thing he does is spy on his sexy neighbor with his telescope, which is something I can honestly say most twelve year old boys would probably do. He’s social in a way that Oskar literally could not be, never managed or understood how to be. His posture is upright, his bearing is comfortable. The movie opens with promise toward his nature, as he’s shown wearing a Halloween mask and fake threatening someone with a kitchen knife (the phrase “little pig” is replaced with “little girl” in this movie for some reason), but that’s about it. He’s a normal kid, and that robs so much of what made him interesting and different as a protagonist in the first place. (Dammit, Americans love Dexter, why did the movie-folks think we wouldn’t love Oskar? Perhaps because he’s twelve, but still.)

The difference in the knives he owns between the original and the remake is a simple visual comparison: hunting knife versus tiny, tiny pocket knife the sort that most people use to clean under their fingernails or open packages. Owen behaves like a normal bullied child, and instead of the theme of the movie being a more subtle question about connection and strangeness, it becomes a question of “evil.”

And that’s where the film gets clumsy. It tries to very hard to make the audience see that Owen is torn up about his girlfriend eating people, that he worries she’s evil, and that the plot of the movie is supposed to be revolving around his moral struggle. The Ronald Reagan speech about evil is played more than once. You cannot possibly get more obvious than that. For me, this is a drastic mistake in tone. There are already hundreds of movies that deal with “is the person I love evil? Can I love them anyway?” It’s a staple of vampire or otherwise paranormal romance. It’s boring, it’s over-done, and it’s frankly unimaginative at this point. To have replaced a subtle, intricate plot about Really Bad People coming together and connecting, finally, in a way they could not with anyone else with a silly plot about “is my vampire girlfriend evil” is just—well, it’s not a good narrative choice, and that’s as nice as I can be about it.

The structure also suffers from the decision to try and market/film Let Me In as a straight-up horror movie. There’s a dissonance between the parts of the plot that try to turn a previously quiet, subtle film into a thriller and the parts that are trying to be subtle. Opening the movie with the burning and suicide of Eli/Abby’s protector-figure, loud ambulances and dramatic policeman then trying to build the rest of the story about their relationship (except the parts with the terrible, terrible CGI) creates a narrative fumble that loses tension. The original was never boring, not for me—it has constant intrigue and tension, even after multiple viewings. The way Let Me In is structured creates a drag between the two disparate types of movie it’s trying to be. (This is why I say I still wouldn’t have given it better than three-stars even if it had been a completely separate, unrelated movie.)

(Let me go back to the CGI for a moment, also. It’s bad. The choice to make Abby go all scary-face and many-jointed “monster” when she’s hungry is just utterly stupid. This is not supposed to be a monster movie, it’s barely supposed to be a horror film, and there was no reason to have such awful CGI anywhere near it. It’s tacky and ugly. It’s cool in Buffy, it’s not cool in this movie.)

The choice to turn Eli/Abby’s protector into a whiny, grumpy old man who loved her as a teenager is also enough to make me want to brain myself on a convenient desk. His scenes suffered almost as much as Oskar/Owen’s when it comes to characterization. One of the most haunting, quiet moments of the original is when he’s caught in the gym with the boy trussed up, ready to kill, and the boy’s friends trap him in the room. He sits with his head in his hands for a long moment as we watch, breathless, hating to sympathize with him but still sympathizing, and then continue to watch as he calmly walks into the shower area and douses himself with acid. I won’t deny the car-crash scene was cinematically interesting in Let Me In, it was damned pretty. But the screaming, in-a-hurry acid bath thing was so much more powerful.

That is really the thing at the heart of why I not only didn’t like Let Me In but found it extraneous and pointless. It is much less powerful, it is clumsy in its narrative and its themes, and it doesn’t know what kind of movie it wants to be. The only things that were kept were the unnecessary things—specific camera angles, for example. Aping camera angles after you’ve already yanked out the thematics and sense of subtlety just seems…kitsch. It’s almost insulting. The film is a distant, dumbed-down and louder cousin of its original source material; it would have been much better to film it with completely original shots because that would have lent it more “credibility,” of a sort, as a different movie.

While it may seem in very, very basic terms to be a remake of Let the Right One In, Let Me In is a loosely inspired and much less fascinating attempt at using the similar characters to tell a fundamentally different story. It’s an all right movie as a stand-alone; not terribly great, though the acting is good and the scenery is gorgeous, because the themes are repetitive and it isn’t doing anything new. Let Me In doesn’t trust the audience to put any puzzle pieces together. From the setting to Abby’s nature (I was so tired of them overusing her dislike of shoes from shot one, it’s much creepier when it’s used sparingly) to the themes, it tries to bash you over the head with everything it wants you, the viewer, to know.

It’s a question of subtle versus loud, fresh versus rehash. I understand the argument that a strange foreign film about socially disturbed young people falling in love and committing acts of terrible violence wouldn’t be successful here. My answer to that, though, is that maybe the box office dollars shouldn’t be what guides decisions in film narrative. I know that’s a pointless and so-very-indie howl into the wind, but really, I would have been so happy with a movie that delved further into the issues of the book and the dark, twisty themes. I would have loved it if it had done those things. But it didn’t, and I don’t. I do, on the other hand, heartily recommend saving your money to rent a copy of Let the Right One In, or just watching it on your Netflix.

It’s quiet, it’s subtle, it’s interesting. Let Me In might be a fine three-star romp for a Friday night movie outing, but it’s not those things.

Lee Mandelo is a multi-fandom geek with a special love for comics and queer literature. She can be found on Twitter and Livejournal.