No matter where or when a steampunk story is set, its roots are embedded in Victorian/Edwardian Britain. It gleefully lifts from that age the fogs and gas lamps, the locomotives and hansom cabs, the top hats and crinolines, the manners and—good Lord!—the language. It adds to this mix its icon of choice: the airship, which didn’t actually exist during Victoria’s reign, but which seems to best symbolise the idea of a glorious, expanding, and unstoppable empire.

All this adds up to a fantastic arena in which to tell tall tales.

There is, though, a problem.

Where, exactly, is the punk?

Okay, maybe I’m being picky. The thing is, I’m English, and I’m of the punk generation, so this word “punk” has a lot of significance for me, and I don’t like to see it used willy-nilly.

The original meaning of the word was hustler, hoodlum, or gangster. During the 1970s, it became associated with an aggressive style of do-it-yourself rock music. Punk began, it is usually argued (and I don’t disagree), with The Stooges. From 1977 (punk’s “Year Zero”), it blossomed into a fully-fledged sub-culture, incorporating fashion, the arts, and, perhaps most of all, a cultural stance of rebellion, swagger and nihilism.

Punk rejects the past, scorns ostentation, and sneers at poseurs. It is anti-establishment, and, in its heyday, was loudly declaimed by those in power as a social menace.

In many respects, this seems to be the polar opposite of everything we find in steampunk!

If we are to use the term, then surely “steampunk” should signify an exploration of the darker side of empire (as Mike Moorcock did, for example, in the seminal Warlord of the Air)? After all, imperialistic policies remain a divisive issue even in the twenty-first century.

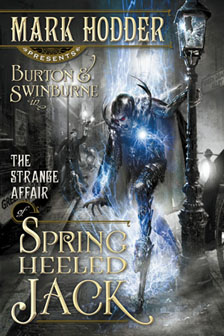

In The Strange Affair of Spring-Heeled Jack, I introduced a social faction known as “The Rakes.” Their manifesto includes the following:

We will not define ourselves by the ideals you enforce.

We scorn the social attitudes that you perpetuate.

We neither respect nor conform with the views of our elders.

We think and act against the tides of popular opinion.

We sneer at your dogma. We laugh at your rules.

We are anarchy. We are chaos. We are individuals.

We are the Rakes.

The Rakes take centre-stage in the sequel, The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man (due March 2011 from Pyr U.S. and Snowbooks U.K.). What happens to them will profoundly influence my protagonist, Sir Richard Francis Burton, leading to a scathing examination of imperialism in the third book of the trilogy.

The Rakes take centre-stage in the sequel, The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man (due March 2011 from Pyr U.S. and Snowbooks U.K.). What happens to them will profoundly influence my protagonist, Sir Richard Francis Burton, leading to a scathing examination of imperialism in the third book of the trilogy.

The point of this shameless self-promotion is to illustrate that the politics and issues inherent in the genre can be approached face-on while still enjoying a gung-ho adventure.

An alternative is to have fun with a little post-modern irony, and for a long while, I thought this was where the genre was going. In the same way that George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman is a wonderfully entertaining character whose politics and morals stink, I thought steampunk might offer a portrayal of empires that seem golden but which, by the end of the story, are obviously tin.

Unfortunately, I’m not sure I’m seeing this. It worries me that the trappings of steampunk might become a meaningless template.

“Punk” is a sociopolitical stance, and if you use it in the name of your chosen genre, then doesn’t that oblige you to at least acknowledge that there are implicit issues involved? Remember, steam technology was at its height just before the world descended into WW1; the airship was at its peak just before the Great Depression; and here we have steampunk flowering on the brink of a massive economic crisis.

Intriguing. Exciting. Perhaps a little bit scary.

My point is this: if you adopt the steampunk ethos, then you need to do so knowingly, because it brings with it certain associations that you might not want to represent.

That’s why it’s vital that you find a way to put the punk into steampunk.

Iggy Pop photo by NRK P3 used under CC license

Mark Hodder is the creator and caretaker of BLAKIANA, which he designed to celebrate and revive Sexton Blake, the most written about detective in English publishing history. It was on this website that he cut his teeth as a writer of fiction; producing the first new Sexton Blake tales to be written for forty years. A former BBC writer, editor and web producer, Mark has worked in all the new and traditional medias and was based in London for most of his working life until 2008, when he relocated to Valencia in Spain to de-stress, teach the English language, and write novels. He has a degree in Cultural Studies and loves history, delusions, gadgets, cult TV, Tom Waits, and assorted oddities.

And see, the Punk is an after-thought, an artifact of the letter KW Jeter sent to Locus that was riffing off the number of ‘-punks’ that were around at the time: Cyberpunk, Splatterpunk, I don’t think Cowpunk had been coined yet, but you get the idea. The Punk was an accident, plain and simple.

Personally, I love Punk, I grew up around the SF scene, but I tend to like my Steampunk on the fun and decidedly less-Punk side.

Chris

I’m with Chris on this one. Let’s have it both ways already. There’s more than one steampunk tribe, so let’s give over trying to make out like the ‘punk’ in steampunk is some sort of a priori argument that settles it once and for all. The movement is fluid. Let the punks be punks, let the fans be fans, and the fashionistas look mahvelous.

Thank you Mark. After reading tour novel and thé récent blog post by Charlie Stross it’s great to read more commentary about the genre. It’s great to get a glimpse of the future volumes.

The word “steampunk” derived from “cyberpunk”. It’s not at all clear that those who coined it used ‘punk’ to mean what Mark does. I’d guess they thought mainly in terms of playing irreverently with Victorian tropes, as punk musicians played irrelevantly with pop tropes. That definition seems to fit well enough with steampunk as it is, even if it doesn’t fit too well with steampunk as some would like it to be.

Who today would not laugh at the notion that the only valid science fiction is that in which human ingenuity triumphs over the aliens? Yet there was a time in which some people actually tried to enforce such demands, attempting to hijack a genre in support of their own political or moral philosophy! I see the demand for the enforcement of a particular philosophy in steampunk as no different.

Whether a literary work is part of a genre depends on whether its readers understand it as part of a genre. Demands by some of those working in a genre (or by some of those criticising it) that all works in a genre should adopt a particular philosophical position have no force. They have historically had no force, nor should they ever have any. Indeed many of the works now considered significant in many genres are those which have driven a steam-powered carriage through such prescriptive postures.

This is what I see everwhere about the whole “Punk” thing and agree with it

“The “punk” in cyberpunk shares a common source with the “punk” in the

punk subculture, but they are not derived from one another. The word

punk is a very old English term that originally meant a prostitute, but

which by the 20th century had evolved into a term meaning an outsider,

a street person, or a ruffian (it’s fairly clear why the punk rock

subculture used this word to describe itself). In cyberpunk stories,

the protagonists were largely “punks” in the pre-modern sense, that is

outsiders and criminals (most often hackers). There is clearly no

link between the people of a steampunk setting and members of the punk

subculture (simply because the environment that produced our modern

“punks” did not exist during the steam age). One could reinterpret

cyberpunk hackers into a Victorian context to obtain “steampunks”

(producing all manner of reclusive scientists and inventors,

professional craftsmen, and military engineers), but that would

probably be reading too much into it. For all practical purposes,

the “punk” in steampunk is a cute turn of phrase used because it sounds

interesting and exciting, without any deeper meaning than that.”

There’s no punk rock in steampunk. That’s just silly, and saying the two are the same is a kick in the teeth to all the punks of the 70s/80s who really did have a political philosophy beyond looking pretty. Steampunk’s fine and all but don’t got telling me kids dressing up in corsets and top hats is the same as people who spent years living on the streets and fighting for social change.

Kelly — I agree with most of what you say, but I think you inadvertently explained what some of us see as being wrong with steampunk. The word (and the subculture itself) has become cute where it once was edgy. I guess that happens with any subculture when it gains acceptance by a lot of people. And maybe that’s why the punk has evaporated from the steam…

I figured that the “punk” in steampunk referred to how a lot of the various characters are sort of anti-establishment. You have women in positions of power, people moving away from their homes and exploring the world, remembering their roots but not being bound by them.

Johnny Eponymous @1 has it. All those whatever-punks that cropped up following cyberpunk don’t necessarily have anything to do with the punk philosophy. The -punk suffix just wound up getting appended to any subgenre, much in the way any political scandal winds up being called whatever-gate. It’s semantically null and is merely intended to reflect the earlier instance in the hearer’s mind.

1) You’re a Brit. From my conversations with Allegra of the excellent Steampunk Magazine, the union between steampunk and politics is more natural. (I think about the UK punk scene in the 70s and how, when punk was exported to the US, punk in general was stripped of its politics to mean something else. You’ll find pockets of them though.)

2) There are plenty of us who do punk in steampunk. Just because we’re not out there pushing our costumes and lit and gadgets on everybody else doesn’t mean we’re not there.

3) From what I understand, part of being punk was that you didn’t have to talk about how you were punk. You just lived it and the proof was in how threatened the establishment was by your mere existence. I could be talking out of my ears, though, not being of that generation myself.

4) Not everyone digs the steampunk ethos, just the aesthetic. There isn’t really anything wrong with that, until they go about appropriating things. You are, of course, free to complain. I most certainly delight in doing so.

5) The revolution will not be — oh, that’s just too mean. Never mind.

@Kelly: Steamfashion’s definition, while widespread, by no means is the final word on steampunk.

Heh! My point is not that steampunkery should be adorned with safety-pins, zips, and an aggressive attitude. My concern is that, if the idea of empire is an aspect of your reference point, then you should have something to say about the socio-political implications of empire.

I’m wondering whether steampunk means something different to Brits than to Americans?

In my mind the use of the term “punk” is similar to the use of “-gate” to describe a scandal. The original Watergate has almost no baring on the use of the term with regards to…oh I dunno.. Charlie Sheen, and yet it is used all the time. “Punk” is now used in a similar way to describe any group or aesthetic that is counterculture.

The way I’d heard it, the punk part of steampunk was the maker part. I’d heard that punk rock was made by people who weren’t a part of the music industry machine, so they had to do it all themselves. Thus, it was my impression that going out and buying a snazzy raygun was less “steampunk” than making your own snazzy raygun out of milk jars and pipes.

But I also deny the primacy of Victorian Britain in steampunk, so take that for what it’s worth. :P

“Punk” has a whole raft of connotations;

http://shakespearessister.blogspot.com/2010/03/on-punk.html (don’t miss the comments) teases out some of them.

“No matter where or when a steampunk story is set, its roots are embedded in Victorian/Edwardian Britain. It gleefully lifts from that age the fogs and gas lamps, the locomotives and hansom cabs, the top hats and crinolines, the manners and—good Lord!—the language.”

The roots of steampunk need not be in Victorian Britain that lady’s Empire. They are set in the 19th century, or the early bits of the 20th. They could be set in a powerful Africa, isolationist Japan, or, really, anywhere. I hate when people try to define steampunk like this: while some of the steampunks (as I hesitate to call them) might merely slap a gear on a corset and put on some goggles, I maintain that “true” steampunk is vastly creative and desirous of a more certain time, before the computer age came and mucked it all up. When life was, essentially, more simple, slower. They celebrate this and think of how things could have gone had we continued along this path, or how else history could have happened. While they love beauty, they also love what’s behind it. Not just the corset, but the woman.

Great article!

The “punk” in steampunk is total nonsense.

As mentioned, punk is about honesty. That was a reaction to hippies from the 60s, as they turned out to be a bunch of masturbating liars (that was a punk comment).

William Gibson, was sort of punk because his stories, at times, were about more powerless people becoming empowered through technology. That’s the direct opposite of fantasy which is mostly about royalty. That is not punk for many reasons. Anyway, Gibson wrote in a kind of “beat poet” style and that mixed with his characters who had punk views create the cyberpunk genre.

After he became popular many “cyberpunk” writers published. Some wrote stories, with plots, and some just wrote what amounted to nonsense because they practiced the writing style only. In that case, you got a bunch of disjointed “poetic” images, and it spawned the terrible “new weird” writers, who I will not name.

So, in writing, “punk” morphed from being about honesty, to being about a writing style, to being about one that makes little sense and is about style over substance. That’s where we are today.

I think the images in steampunk are “cool” but really, what are the stories about? I don’t get alternate history. Other than escapism, I can’t see the value.

Actually, as I’m writing, I may have discovered the punk. Cyberpunk is about beauty and about mastery, and how many people have that in real life?

@Messmer– While I heartily agree that Victorian Britain is definitely not the only place where steampunk can put down roots, there are a few other points you make that are bothering me.

—while some of the steampunks (as I hesitate to call them) might merely slap a gear on a corset and put on some goggles, I maintain that “true” steampunk

“More steampunk than thou” is an attitude that has no place in this genre. If we want more people to enter into steampunk, then we need to not sneer at them if they choose to associate themselves mainly with the cosplay side of fandom. Some people are in it for the aesthetic, and with a genre that has such an iconic, striking visuality, that’s to be expected.

—When life was, essentially, more simple, slower. I always find this assertion about steampunk really odd. If we wanted to celebrate truly simple things in life, we’d be writing farmpunk or Amishpunk. Steampunk takes this ostensibly “simple” time of the Victorians (it was nothing of the sort) and speeds it up with fantastical technology, like airships and ray guns. We make it more complicated and faster.

–Not just the corset, but the woman.

Minor thing, but plenty of men in steampunk wear corsets.

/Iggy Pop/ /blink/ /blink/

That reminds me- I’ ve got some major ironing to do this afternoon.