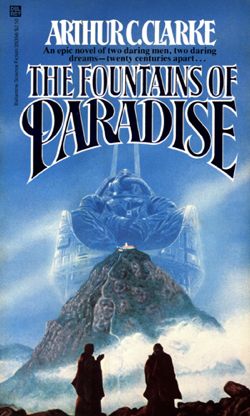

The Fountains of Paradise won the 1980 Hugo, but it’s a much more old fashioned book than you’d expect for something published in 1979. It’s hard to believe it was written in the same year as Kindred (post), Tales of Neveryon and On Wings of Song. In fact, it’s hard to believe it was written on the same planet. The Fountains of Paradise is a story of a man building a beanstalk, a space elevator, from Sri Lanka to orbit. It’s an engineering project that runs into trouble with politics, with office politics, with some monks on a mountaintop, and of course technical problems. The characterisation is very thin, and the plot is even thinner. It contains a number of Clarke’s hobbyhorses. Even in 1980 I didn’t think it was one of Clarke’s best books, and I don’t think I’ve re-read it between then and now.

If you haven’t read this book and you want to read it, you want to read it for the engineering challenges, and I’m not going to spoil them. They remain futuristic and mildly interesting, the same as they were in 1980. But there will be spoilers for everything else after the cut.

Now, of course, this 2154 is a retro-future. The computers are mainframes, but there are terminals for remote accessing them and you can query information and I’d say Clarke has done pretty well. I kept imagining it as the internet of about 1996, you had to hope there was a free terminal but when you got one there was Google. You could select items to search on, and everybody has themselves on their list of things that send alerts. The way this is integrated with communications involves everyone having one lifelong identity number and if you don’t know it you can Google it. (Well, the equivalent of Google.) There’s an AI called Aristotle who can talk to you and is running their net, which isn’t called a net. This is pretty good, but it’s four years after The Shockwave Rider and four years before Neuromancer.

All the characters are very thin, but it’s still noticeable that there are almost no women, and the one woman there gets less characterisation than anybody else. She’s a journalist. There are no female engineers on the project, and we see one female grad student scientist in the background. There’s also a mention of a romantic involvement in the distant past of Morgan, our engineer-hero, and a female servant of Rajasinghe, a retired diplomat. This is absolutely it for female presence—and this is why I keep saying that Heinlein deserves points for bothering with women even if he got things wrong.

Religion has been abandoned because an alien space probe pointed out that it was illogical and very few other intelligent species had anything like it. I can imagine a lot of reactions to an alien space probe saying that, but everyone saying: “Oh, why didn’t we notice that already…” and packing up their toys doesn’t seem like a plausible one for the world I know. But is it this world? The space elevator is being built in Sri Lanka, on the only possible mountain in the world for a space elevator. But it isn’t Sri Lanka, it’s “Taprobane,” and we’re told in the afterword that Clarke moved it onto the equator and doubled the height of the relevant mountain. He also calls India Hindustan and refers to the colonial Caledonians, Hollanders and Iberians, making me wonder if this really is meant to be a slightly alternate world. If so, it might explain why human nature is so different.

Taprobane is problematic in other ways. There’s a lot about the ancient Singhalese culture, the whole conceit of the book is that the space elevator is completing the two thousand year old vision of a king of Taprobane who wanted to reach heaven. And there’s one Taprobanian character, Rajasinghe, a retired international mediator, who is dealt with very respectfully. But he doesn’t do anything — he’s the most passive character imaginable, introducing people to each other, in contented retirement at the beginning and the end. It’s hard to see why he’s there and why he’s a point of view character. But he’s just one guy.

There are also some monks who insist on staying on the top of the mountain, being among the remaining handful who haven’t given up religion. One of them, a mathematical genius, leaves the mountain and joins the weather control group to disrupt the weather when the proof of concept testing is done. By chance his disruption sends butterflies up onto the mountain where they could otherwise never reach, causing the monks to abandon it to the engineers. This would be less problematic if the genius monk wasn’t a European convert. It starts to feel as if the Taprobaneans are all entirely passive.

The engineering challenges are well thought through in a traditional old-fashioned science fictional way. It must have been quite difficult to think of a situation where a daring rescue could be possible. Clarke makes this aspect of the book work. There are also occasional passages of poetic writing about the universe and science and engineering, which are the thing for which I have always read Clarke. Nevertheless, my strongest feeling on finishing this book is absolute disbelief that this was considered good enough to win the Hugo. This is thin stuff, thin and stretched. There are better things to do with your afternoon.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two poetry collections and nine novels, most recently Among Others, and if you liked this post you will like it. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.

Come again? Are the monks terrified of butterflies? How does this make any sense at all?

(I’ve never read the book, and probably won’t after reading this review. So go ahead and spoil me.)

I was going to say this on Sunday, but I’m pretty sure this won the Hugo only because Clarke had announced it was his final book. Looking back now, it is fairly clear that he decided to retire due to the death of his long-time partner (to whom the book is dedicated). That may also explain a lot of the weaknesses relative to his other work (problems like weak female characters are more inherent). His partner died while he was midway through writing, and I think a lot of his spirit and energy understandably drained away. A few years later, of course, he got over his grief and started working again. It might have been better if he had just set this aside until he was ready to work again and picked up from where he left off.

I remember that alien-disproving-God thing, and I had the same reaction you did. I think they disproved St. Anselm or something, and yeah, I thought about fundamentalists the world over thinking, Oh, they disproved Anselm, well, I guess I’ll just stop going to church then. Most of them had probably never even heard of Anselm. Also, I thought it was interesting that Clarke needed some Big Sky Creature to base his atheism on.

What usually happens when you point out a devastating flaw in a religion is not that you get one less religion, but that you get at least one new one.

@jaspax: There’s a prophecy of some sort that if these butterflies ever reach the temple/monastery (can’t recall which one it is), then the monks would have to leave. Something the butterflies wouldn’t normally do since it’s too high up and they don’t climb that high.

(Spoilers so the text is hidden)

I remember this book first coming out and it’s probably the first book where I was aware it was “the new book by this author I like” for this reason, I have a soft spot for it. Also, it was my first encounter with the idea of the beanstalk.

Jaspax: Cybernetic Nomad is right.

Cybernetic Nomad: Don’t re-read it if you want to retain that soft spot. My vague memories were much better than it actually was this time through.

In re the religion, I suspect that Clarke himself were converted by logical argument from a wishy-washy Christianity to atheism as a teenager and believed sincerely for his whole life that everybody else would be similarly convinced if they just met the right logical argument. Only — this really isn’t the way the world works.

Nice that there is a reverse Chaoscliche, though – the storm causes the butterflies’ wings to flap, rather than the other way round.

I liked this when I last read it but that was 30 years ago.

I reread the book a couple of years ago, and was surprised by two things – first, the way that Clarke predicted that computer networks would render all factual questions pretty easy, so data search contests asked questions like “What was the rainfall in the capitol city of the world’s smallest nation on the day the second largest number of homeruns was scored in college baseball?” and the fact that Clarke talks about Merle Tuve (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merle_Tuve) and his work in atmospheric science – inbetween my first read of the book in the 1980s and the reread in 2009, I had started working at a facility where there is a building named after Tuve.

I thought this book was pretty boring when I read it. I wouldn’t recommend it for anyone, though the concept was interesting. I think Clarke had a little bit of the dreamer in him. There is seldom that much conflict, and he really seems to believe in men of goodwill. Nice Utopian concept but not very close to reality.

On the abandonment of (most) religions in “Fountains of Paradise”. Most of the major religions were already in the process of dying off when the alien probe appeared. The probe just gave a last nudge to a process that was already happening.

One little note is that the leader of the monastery is called Mahanayake Thero (which seems to be a traditional religious title?) . A character with that title is an important character in Clarke’s novel “The Deep Range”. The two novels also share a plot point (which I think also appears elsewhere in Clarke’s work) that Buddhism is the only real survivor among the world’s major religions.

I liked it a great deal more than you did — I found it quite charming, and much better than anything Clarke had done in a long time or would do in the future.

Of course the characters are thin, though I don’t think Vannevar Morgan that badly done, and the women non-existent, and there are sillinesses such as the bit you note about everybody just abandoning religion because the aliens said so. (I don’t think an alternate history would explain it — you need alternate humans, like those Banks posits for the Culture.)

But for all that I just enjoyed the novel — partly, perhaps, because it seemed like real pure Clarke of the ’50s. The mystical aspects to it worked for me, and the ending I found quite moving.

(I note that I read this only a decade or so ago, so this isn’t the 20 year old me at first publication of the book talking.)

Hmmm, I remember liking the book in the early 80’s and liking the engineering challenges… Did not notice the weaknesses at the time. Would probably notice them now!

This was the first paperback that I (aged 14 at the time) had ever purchased brand new. I have a real fondness for the novel, although the 45-year-old me is certainly able & willing to acknowledge its flaws.

Clarke’s work can — and in my opinion should — be read for the sense of wonder and the Utopian spirit in which it was written. There is didacticism within his work; a strong urging (advocacy in the form of prose) for the human race to strive for ‘something better’ . . . a firm belief that committed scientific pursuit will lead to vastly improved lives for the human race on the whole. In this way he can be seen as the counterweight to Brunner’s dire warnings and Ballard’s tales of scientific advancements resulting in the serious wounding (if not death) of the human spirit.

I think the book picked up some sensawunda points as well. Space elevators are old hat now, but the idea was still really new and fresh in 1979.

I didn’t know that his partner had died during the writing but, yes that seems to be right.

Doug M.

Really? I’m the first one to mention the following?

Poor Charles Sheffield wrote Web Between the Worlds half a world away from Clarke and at the same time, in a world where there wasn’t trivial, ubiquitous, fast international communication. From Baen’s webscription for WBtW:

All this made me feel somewhat insecure. At the time I was busy writing a whole novel centered on beanstalks. Suppose that the readers and reviewers rejected the whole thing as scientifically impossible.

And then, in the fall of 1978, I heard from Fred Durant. He was and is a friend of mine, and Arthur Clarke’s oldest friend in the United States. Fred lived just a couple of miles away from me, and he spoke with Clarke frequently by telephone. Arthur, he told me, was finishing a new novel—a novel in which a space elevator was a main element.

I won’t say I was pleased. Nervous is a better word. I had never met Arthur Clarke, but at Fred Durant’s suggestion, not to say insistence, I took my completed manuscript and sent a copy to Clarke in Sri Lanka. I had no idea what to expect; what I certainly didn’t expect was what came: first, a very friendly letter from Arthur Clarke, and, soon after, an open letter from him to the Science Fiction Writers of America, stating that coincidence, not plagiarism, lay behind the fact that two books were to be published in 1979 with strikingly similar themes. Not just the space elevator, but each book had as main character the world’s leading bridge-builder; each one employed a device known as a Spider.

Fraffly sorry, but I’m going to have to be contrarian and say I quite enjoyed it when I read it in 1980, and every time since – though not having it in my private library, I can’t say I’ve read it recently.

I always enjoyed reading him for the detailed way he looked at people facing scientific and engineering challenges; also for the ill-disguised hopeful mysticism that lay behind works like Against the Fall of Night, Rendezvous with Rama, and 2001.

The Fountains of Paradise doesn’t compare with the last three books – I think that in a century or more, people will be reading them, and excerpting the others … that being said, I would still re-read it, again and again.

(Incidently, speaking of an earlier topic on this site, about topics of irritation being topics of inspiration; ie, I can do better than that: this book was one of my first such itches. I started drafting stories of what it would be like to live in a world where, thanks to the beanstalk, getting into orbit was at the same level of cost that getting from London to Sydney was in the 1840s, and interplanetary travel was a magnitude more expensive. And if you had the money, you could afford it, and many people not infrequently did. Now, if I did rewrite those first drafts, I would have to recast their dramatis personae, because I doubt the US is going to remain the pre-eminent space power for much longer. And having an accidental romance between the conflicted (civil engineering? beauty consultant?) Xiexie and the equally conflicted (programmer? Bollywood god?) Ram, who are thrown together (dis)courtesy of a beanstalk glitch, is going to be so much more fun than the original mishmash … :)

I just finished re-reading this book and once again, I am completely taken by it. True to form and contents, real old-school SCI fi with the emphasis on SCI. The amazing interweaving of the Taprobanian/SriLankan cultural atmosphere and the highest scientific aspirations, the engaging story of an amazing human set to reach for the sky are superb. The book has its naive points and its weak points (like, yeah religions probably would not have been so readily abandoned – but to me that part read more as an amusing bit of pre-Internet trolling by the master than anything else and at any rate it was not a particularly important part of the story.

Now I have to confess that criticisms of the nature of “there were no women among the ONE /TWO/ limited number of characters” annoy me. It’s a story, and a story needs to be told about something. It can not be about everything and everyone at once. As a woman scientist, I am perfectly capable to enjoy a story featuring people other than the ones exactly like me, and I intensely dislike when deep interesting stories get discounted on grounds of not having women in them. I also understand that there were not that many women engineers back then anyway. I find the criticism of the passivity of monks even more annoying – since if you know anything about Eastern philosophies you know that activity is not high on their lists. The fact that it was the activity of an American convert that actually brought about the end to their peaceful living on that mountain is quite important.

So yeah – if it is important for you that there are active women in key positions in a novel – skip this one. If you appreciated old-school sci fi and certain level of depth – read it.

The Fountains of Paradise is a great book! I love the mysticism and dreaminess of the setting.

As for the butterflies, that was an impossibility that was made real: butterflies never go up to the summit (too cold and too high, I guess) and a prophecy stated that if they ever reached the monastery the monks would have to leave. Since the impossible suddenly became real, via one of the monk’s, then obviously the heavens wanted them out and they left.

I have to admit I read the novel years ago maybe ’85. But what I always have remembered is the concept of instant global communication. This did not exist at the time. I remember the character of the female journalist- people would “tune in” to watch her especially because she was always in the location of whatever was most important that was happening in the world at the time and she was the most popular of many options She travelled with a camera crew. Just A TV reporter, really, but with access to this network that everyone could link to at any time. She was always reporting live. I fantasized about having a complete mobile telecommunications system. Now anybody can do that on Twitter! He presaged that and it was just a background part of the plot which I guess is why I think nobody seems to notice.

Re the personal loss Clarke suffered in 1977: it wasn’t his partner. According to Neil McAleer’s biography, Clarke became close friends with his business associate Hector Ekanayake, and eventually the entire Ekanayake family became a kind of surrogate family for Clarke. In particular, he came to think of Hector’s younger brother, Leslie Ekanayake, as the son he had never had. That was why Leslie’s sudden death in an automotive accident hit Clarke so hard. As DemetriosX @2 notes, he dedicated this book to his memory. I have the strong impression that the character of Kumar in The Songs of Distant Earth was partly based on Leslie Ekanayake as well.