After completing At the Back of the North Wind, George MacDonald again returned to writing realistic novels for a time, until his imagination was once again caught by the ideas of princesses, mining and goblins, all leading to perhaps his best known book: The Princess and the Goblin, published in 1872.

Aside: I have never been able to figure out why the title says “Goblin” and not “Goblins.” The story has lots of goblins of various shapes and sizes—MacDonald even takes a moment to give their histories and explain how their pets evolved into monsters. (Darwin’s On the Origin of Species had been published in 1859, and although I don’t know if MacDonald actually read it, he had certainly absorbed some of its arguments.) Yes, I realize the goblins hope to attach the princess to one specific goblin, but still. Moving on.

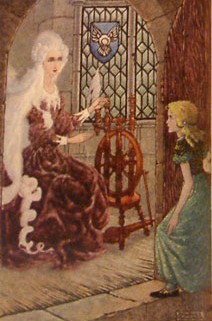

Irene, an eight year old princess, is bored. Very bored, despite oceans of toys—so many that MacDonald literally pauses his narrative to beg the illustrator not to bother trying to depict them. And because it is cold and wet and miserable and even with the toys she has nothing to do, she climbs up a staircase she has never explored before, and finds an old woman there, spinning. The woman, she discovers, is a grandmother, of a sort, and also a fairy.

Also, Irene lives very near some miners, and some evil goblins. You can tell the goblins are evil because they hate poetry. (Although, in defense of the goblins, if the only poetry they’ve been exposed to is MacDonald’s, their hatred may be justified. I also can’t help wondering if someone said something about the poetry to MacDonald, who good-humoredly responded with turning his poems into actual weapons of mass destruction. I’m telling you, just terrible stuff.) Apart from the poetry issue, they also want to eat people, have major issues with toes, and terrify the miners.

But even here, the compassionate MacDonald hints that the goblins did not exactly turn evil by choice: the goblins were, he thinks, former humans who fled underground to avoid high taxes, poor working conditions, corruption and cruel treatment from a former human king; only then did they evolve into toeless, evil creatures, a none too subtle reference to the often appalling working conditions faced by miners and other working class people in Victorian times. The work that these men and children did often could and did cause physical injuries and disfigurations; nonfiction literature of the period speaks of the inhuman appearance of 19th century miners. MacDonald continues this theme by noting how many of his human miners (working near the goblins) are forced to work overtime, in dangerous, solitary conditions, just to earn enough money for necessities and clothing, even though they work very near a pampered princess with too many toys to play with.

These bits are also the first hint that this tale is going to be about a little more than just a princess and a goblin, whatever the title may say, and is going to spend a surprising amount of time chatting about toes.

In any case, when Irene tries to tell people about her grandmother, she finds that she isn’t believed—upsetting, and also odd, given that the people she is telling are quite aware that they haven’t been telling the princess about the various evil creatures that come out at night, so why they wouldn’t believe in a fairy godmother who comes out during the day is more than a bit odd. Quite naturally, she begins to doubt the reality of her grandmother’s tower—but just begins.

Meanwhile, that doubting nurse leaves Irene outside just a little too late in the evening, allowing Irene to meet Curdie, a miner’s son, who just might be part prince (MacDonald has just a touch of the “royalty are better people than the rest of us” in him). Part prince or not, he is still of a lower social class than the princess, leading to some chatter about social distinctions and the perils of kissing across class boundaries, all of which seems a bit much for a friendly kiss from an eight year old, but this is Victorian England. Curdie returns to the mines, where he overhears the goblins plotting; eventually, his curiosity leads to his capture by goblins.

The book really gets going once the goblins enter it again. They may be royal (well, royal by goblin standards), but they are certainly not bound by royal dictates to be polite, and they have some hilarious dialogue as a result. They also provide some real stress and tension, and this is when the book’s adventures get going, and when the book starts hitting its psychological stride. On the surface, yes, this is about a princess and a boy attempting to stop a goblin invasion. But that’s only the surface. The core of the book—made clear shortly after the goblins reappear—is about faith, about holding to your beliefs when you know you are right, even if others, and especially others who matter to you very much—keep telling you that you are wrong.

Already doubted by her beloved nurse and father, Irene finds, to her horror, that Curdie cannot see the bright thread that leads them from the darkness to the light, or see the woman who gave Irene the thread. An infuriated Curdie believes that Irene is making fun of him, and leaves in fury. Irene cries, comforted only when her fairy grandmother patiently explains that seeing is not believing, and that it is more important to understand, than to be understood. Curdie’s parents gently chide him for his disbelief, explaining just when certain things do have to be taken by faith.

These are beautiful passages, symbolic of the Christian faith in things that must be believed because they cannot be seen (especially with the motif of the light leading from darkness and evil), but it can equally be applied to other things. It’s a plea for tolerance, for understanding, for listening, and—surprisingly for MacDonald—not all that preachy, despite the way I’ve summarized it.

And it leads to one of the most satisfying scenes in the book, when Irene, finally convinced that she was, indeed, right, faces down her nurse, who has been, throughout the book, entirely wrong. Remember back when you were eight, knowing that you were right and the adults were wrong, but you couldn’t do anything about it? Irene, of course, as a princess, has access to slightly better resources, but it still makes for a satisfying scene—one touched with more than a bit of Christian forgiveness.

I am also oddly fond of the Goblin Queen, even if she wants to eat Curdie. (Maybe because she wants to eat Curdie.) She’s fierce, practical, and generally right, and never hesitates to stand up to her husband or refuse to show him her feet. (It helps that she has some of the best dialogue in the book.) I am considerably less fond of the other women in the book—Curdie’s mother, pretty much the stereotypically good mother of Victorian fiction, needing the protection and support of the men of the house, and Lootie the dimwitted nurse, often rude and dismissive, and more critically, prone to putting her charge into danger, and who needs to be completely removed from her position, like, now.

But against that, as said, the book offers the Goblin Queen, the calm, insightful fairy godmother, and best of all, Irene, perhaps a little too sweet and naïve, but able, with considerable effort, to overcome her very real fears and doubts. It probably helps that she’s eight, an age where it’s easier to believe in magical strings, but on the other hand, this is also the age where she has to struggle against the seeming omnipotence of those older than she, and find her own beliefs and faith. Which she does, quite well. If I doubt some of MacDonald’s comments about real princesses (specifically that they are never rude and never lie), I find myself definitely believing in Irene. (It’s only fair to add that this is not a universal belief: Irene’s sweetness and cuteness may grate on some readers.)

With its quiet social and religious commentary, along with, for once, a fairly tight plot, this is one of MacDonald’s best and most satisfying books—although I still have to urge you to skip the poetry, since reading it might cause you to turn into an evil goblin—or worse, not get to the good parts of this book.

Mari Ness doesn’t hate poetry, she swears. Just the poetry in these MacDonald books. She lives in central Florida.