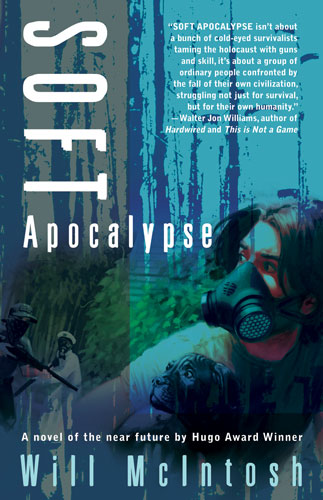

Jasper and his tribe of formerly middle class Americans describe themselves as nomadic rather than homeless: they travel around the Southeastern U.S., scraping together the bare minimum to survive by spreading out solar blankets or placing small windmills by the highway to collect energy from passing cars, then trading the filled fuel cells for food. Fewer and fewer people want to deal with the “gypsies” who use up dwindling resources, and often they meet with indifference or even violence. Jasper was a sociology major, but those skills are no longer in demand in 2023, about ten years after an economic depression set off the Great Decline and society as we know it gradually began to fall apart. So begins Will McIntosh’s excellent debut novel, Soft Apocalypse.

One of the most interesting aspects of Soft Apocalypse, and something I’ve rarely seen done so well in a dystopian novel, is the fact that it shows society in the early stages of dissolution. Many post-apocalyptic stories show a finished end product, an established dystopia in which the Earth has already been torn apart and people are trying to survive the aftermath. Other stories show the events right before and during the actual earthquake/meteor strike/plague, with people trying to make it through the disaster as it happens. Soft Apocalypse instead happens during a period of gradual but inexorable decline: as the back cover says, the world ends “with a whimper instead of a bang.” If Robert Charles Wilson’s excellent Julian Comstock: A Story of 22nd America is set in post-collapse U.S.A., when enough time has passed for society to fall back into established structures and classes, Soft Apocalypse could almost be set in the same world, but a couple of centuries earlier and during the gradual collapse of the previous system.

“Gradual” is the key here: Soft Apocalypse shows normal people clinging to the shreds of life as they knew it, while things slowly go from bad to worse. Many still hope that the economy will pick up and life will go back to what it used to be. Even though the streets are filled with homeless people and unemployment stands at 40%, others can still drive a car to work. Walmart still operates its stores, even if they raise prices to extortion-like levels whenever there are reports of a new attack or designer virus. When they can afford the electricity, people still watch cable news to find out about wars and disasters abroad, and even if there’s a developing pattern of widespread war, it’s all distant enough to seem unreal—until it starts getting closer and closer.

Soft Apocalypse consists of ten chapters and covers about ten years, with anywhere from a few years to a few months passing between chapters. Jasper narrates the story in the first person, dividing his attention between his struggle for survival in the slowly disintegrating society and his attempts to find love—because even during a slow apocalypse, people still crave romance, improvising dates and respecting the social niceties. When it comes to his love life, Jasper sometimes reminded me of a less music-obsessed version of High Fidelity’s Rob Gordon: a generally nice, sensitive and intelligent guy who isn’t aware of how clueless he occasionally acts when it comes to women. Throughout the novel, Jasper tries to find love while doing his best to survive the dangers of the collapsing society around him.

Negatives? Very few, if any, and definitely all qualified with a solid “but.” Early on, the novel feels more like a collection of connected short stories because so much time passes between the chapters, but Jasper and a well-drawn cast of side-characters pull everything together until a plot emerges, and even before that happens, the story is hard to put down because of the gorgeous but bleak descriptions of life during societal collapse. Also, “bleak” may be too mild a term for some of the horrors that Jasper and his friends encounter: there were a few times I just didn’t expect Will McIntosh to push things that far, but at the same time, you have to admire him for not shying away from scenes that would surely be cut from the Hollywood version. The plot sometimes seems driven by random, often violent events, but then again, life in this novel’s environment would probably be full of random, violent events. More importantly, even though it may not seem that way early on, all of them have a meaningful impact on Jasper’s personality, leading to an ambivalent ending that I’m still coming to terms with.

Soft Apocalypse, while not perfect, is a great achievement for a debut. It took me by surprise early on and never let go. It’s a short, effective dystopian novel that should go down well with people who enjoyed the aforementioned Julian Comstock: A Story of 22nd America by Robert Charles Wilson or even The Rift by Walter Jon Williams. (Maybe not coincidentally, Will McIntosh participated in Williams’ Taos ToolBox workshop in 2008.) The real sadness of Soft Apocalypse is seeing normal people operating under the illusion that life will still go back to what it used to be. They try to hold down a job or complete a post-grad degree, and even though the world falls apart around them, the changes are too gradual for them to lose hope completely. It’s like watching rats in a maze, unaware that their paths are slowly being closed off around them and the maze is starting to catch fire at the edges. A soft apocalypse, indeed.

Stefan Raets is a reviewer and editor for Fantasy Literature.