Before becoming a novelist, Edith Nesbit had penned several fantasy and horror stories for both children and adults. Even her more realistic Bastable novels displayed a strong familiarity with fairy tale motifs. So it was perhaps not surprising that, having done as much with the Bastables as she could, Nesbit next turned to a novel that combined her love for fairy tales with her realistic depictions of a family of quarrelsome, thoughtless children: the charming, hilarious Five Children and It.

As the story begins, the children—Cyril, Anthea, Robert, Jane and the Lamb (a toddler frequently dumped on his older siblings) have been left by their parents with a couple of servants at a country house about three miles away from a railway station, which prevents all sorts of opportunities for fun and mischief. Perhaps reflecting Nesbit’s own hands-off approach to child rearing, the children seem just fine without either parent—well, just fine, if you ignore their problems with a very bad tempered fairy creature, but to be fair to their parents, bad tempered fairies are just one of those things that can’t be planned for.

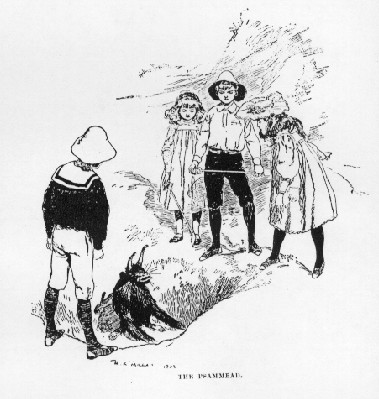

This particular fairy, a Psammead (Nesbit made up the word) has the power to grant wishes, something it dislikes doing since granting wishes takes a lot of energy and rarely goes well. Nonetheless the Psammead agrees to grant the children their wishes—while warning them that their wishes will expire promptly at sunset. The delighted children, happy with even temporary wishes, start wishing—not wisely or well. Not helping: after the first wish, the Psammead prevents any of the house servants from seeing the wishes or their effects, leading to vast confusion.

The theme of wishes going badly is not a new one in fairytales or popular folklore, but Nesbit has a lot of fun with it here, largely because the children remain convinced that all they have to do is wish wisely, and all will be well. Alas, they do not wish wisely. Their first wish, to be beautiful, means that no one can recognize them and they end up going hungry. With their second wish, they find that unlimited wish-begotten funds are looked upon with great suspicion by strange adults, especially if the child with the funds happens to be dirty. And so on, with each wish leading to further and further disaster.

The length of the novel allows Nesbit to play with both types of wishes gone wrong—the well-intentioned, but poorly thought out wish, and the completely accidental wish. The children actually do learn from their mistakes, but these lessons never seem to do them any good, and if they rarely repeat a mistake, they have no problems making entirely new ones. Since this is a children’s book, the punishments are never anything more than missing meals or dessert or getting sent straight to their rooms or enduring long lectures or having to explain to a group of puzzled adults just how they managed to get to the top of a tower with a locked door or having to do a lot of walking and exhausting cart pulling. At the same time, Nesbit makes it clear that their foolish wishes most certainly do have very real consequences, hammering home the old adage of be careful what you wish for.

Although with one wish, the children actually learn something quite valuable—their baby brother is going to grow up to be a completely useless person, and they will need to do some fast intervention to prevent that from happening. Unfortunately, they are soon distracted by yet another disastrous wish, so it’s not clear if they remember their sibling duties or not.

The sharp social commentary from Nesbit’s earlier novels is toned down here, except in the chapters where the children wish for money—and swiftly find that large sums of money held by children of questionable and very filthy appearance will raise suspicions in the most kindly minded adult, and particularly in less kindly minded adults, and the chapter where Robert turns into an eleven foot giant—to the delight of adults who realize that significant sums of money can be made from this. It takes some quick thinking to save Robert before sunset.

Outwitting the consequences of their own wishes takes all of the ingenuity of the four children—and between them, they have quite a lot. But that also leads to what makes this novel so satisfying. If a lack of thought gets them into trouble, thinking gets them (mostly) out of it, if not without some consequences. Much of the fun lies less in seeing how the wishes will go wrong and more in how the children will get out of this one. And if the children of this novel lack the distinct personalities of children in other Nesbit novels, they are also—and this is important—considerably less annoying and superior, making them far more easier to sympathize with and cheer for.

One warning: the chapter where the children accidentally wish for Red Indians in England does use numerous stereotypical depictions of Native Americans, largely because the wish is based on the image the children have of Red Indians, which in turn is based entirely on stereotypical 19th century images. With that said, Nesbit clearly does not intend these to be realistic depictions, or taken as such (no more than the knights who appear in another chapter are meant to be realistic knights), and the Red Indians prove to be more competent and honest than the children. Another chapter introduces gypsies, also using stereotypical language, but at the end of this chapter Nesbit does move beyond these stereotypes, assuring readers that gypsies do not steal children, whatever stories may say, and presenting one kindly, wise gypsy who gives the Lamb a blessing.

Mari Ness is positive that she would be able to use her wishes wisely, but so far, she’s been unable to convince a single fairy to believe her. She lives in central Florida.

IIRC, Nesbit’s heavy stereotyping means that her Red Indians don’t speak Heap Big Wampum talk, they speak like a Longfellow poem. It’s still stereotyping, but it’s doing its best to be harmless.

Nesbit always does this; her view of foreigners always takes the form of mild literary humor. In Enchanted Garden she portrays a “French accent” by literally, word-by-word translating the French into English–so, a character asked about her painting says, “I achieve a sketch of yesterday.” Of course this has nothing to do with how French speakers speak English.

It’s a very Victorian British kind of humor, but as the pathology goes, it’s a pretty mild case.

The general crotchetyness of the Psammead always amused me. The children are much less useless then the Bastables- I shudder at the thought of Oswald with a magic-wishing ability. Even ending the wishes by sunset couldn’t save the world from him. (Sunset in England in summer is somewhere around 9 pm, if I recall correctly)

To everybody: one sentence up there should read, “…done as much with the Bastables as she could at the time…” Nesbit liked the Bastables enough to bring them back in a couple more books that I’ll be discussing soon.

@seth e – Nesbit’s stereotyping is very mild for its era, and, unusually for her era, she’s fully aware that she is stereotyping. (And, this may be the American in me, but I’m far more bothered by her casual if occasional use of the n-word, which has been deleted or altered in many editions by editors sharing my feelings here.) But I still think it’s worth pointing out.

@Pam Adams – These kids are also a lot more likeable than the Bastables in general. Their cause may not be as critical or important as restoring the ability fo the family to pay its basic food bills, but I found myself cheering them on a lot more.

@MariCats – It’s true, Nesbit’s totally aware of what she’s doing, and even poking fun at the stereotypes she’s using. It’s not really from reasons of racial consciousness in the modern sense, but still.

And the n-word, yeah. Reading older editions of Wodehouse was a revelation for the same reason.

i loved this book as a kid. thanks for the reminder! just downloaded it free on amazon kindle. time for a trip down memory lane. :-)

@seth e. – It’s the complete casualness that gets me; I’m not accustomed to thinking of it as a casual sort of word, but that’s how she uses it; she doesn’t seem to assign much of a negative meaning to it or think about it at all, particularly startling since she did give at least some thought to stereotypes about and words used for other minority groups.

@jc1239 – Free ebook editions of classic books are one of the genuine wonders and delights of our era :)

MariCats, in her time the “n” word was used casually which is a good reason for it to “jar” us to see it used that way.

@DrakBibliophile — :: nods :: I’m aware that in her time people did use the word casually, and she’s following general use, but she also was very aware of the power of words and names, and quite capable of using them to showcase the problems of stereotyping (as with the Red Indian part of this book, where stereotyping is one reason the kids get into further trouble) and assumptions. Thus the jarring feeling I have.

It’s not clear to me when you say “Nesbit made up the word” whether you know that Psammead is from real Greek roots — compare Dryad, from ?????, “tree”; the Psammead calls himself a “sand-fairy”, and ?????? does indeed mean “sand”.

I was shocked to run across the “n:” word in Geoffrey Trease’s Bannermere series- true, it was used as a dog’s name by an uneducated person, but still- when you consider the time- late 40’s-early 50’s, and Trease’s general thrust when writing…..

@Pam Adams – Wodehouse uses it in exactly the same way. In later editions (the first version of those stories I read), the dog’s name is changed to “Blackie,” which, in retrospect, hm.

The unthinking casualness is what makes it a more telling, more lasting kind of racism than the easy, obviously evil kind. Wodehouse at least is using the word fondly.

David_Goldfarb, I think the “making up” of Psammead refers to the idea that folklore doesn’t refer to a fairy called a “Psammead”.

Edith Nesbit made up the term in the same way that Tolkien “made up” the term hobbit.

Except that Tolkien didn’t consciously intend the word hobbit to mean anything: the etymology ‘hole-dweller’ is a total retcon.

I don’t think the Lamb is necessarily destined to grow up to be so horrible as he’s portrayed here: rather, this is what he’d be like if he became an adult without actually experiencing any maturation.