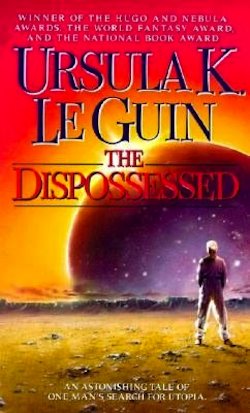

The Dispossessed (1974) is a novel about which one can say a great deal. It’s a Hugo and Nebula award winning novel. It’s an undisputed SF classic, despite the fact that some people hate it. It’s a portrait of a working scientist as a creative person, which is unusual, and it is about the discovery of a theory of physics that leads to a method of faster than light communication, which is an oddly standard SF trope. It’s an examination of anarchy as a method of political organization. It’s about two societies that are each other’s moon and which mirror each other.

When I was twelve, it was the second best book I had ever read. It was the first adult science fiction novel I read, and the amazing thing is that it was such a good one. I didn’t hit on it by chance, of course, I came to it because I had read the Earthsea books. I read it, and I immediately read it again, this time reading it in chronological order, because I was twelve and I’d never before read a book where the events happened out of order and I wasn’t sure I liked it. I spent a long time thinking about why Le Guin used this helical structure for the novel, and over time it has come to be one of the things I like best about it.

What I want to talk about today is the structure and the style.

The Dispossessed is the story of one man who bridges two worlds, the physicist Shevek who grows up on the anarchist world of Anarres and travels to the propertarian world of Urras, which his ancestors fled two hundred years ago. It is in many ways his biography, and stylistically in the way it explains context it more closely resembles historical biographies than most other SF. This is a story focused on Shevek, and yet one that remains resolutely a little outside him, in the omniscient point of view. We sometimes get a glimpse of his thoughts and feelings, but more often we are drawn away and given context for him.

Le Guin begins on Anarres, with Shevek leaving for Urras, with no context as to who Shevek is and why he is leaving. The book then goes back to his childhood, and we alternate chapters of his life on Anarres leading to his decision to leave for Urras, and his life on Urras culminating in his eventual return home. We’re being shown the societies and their contrasts, and the chapters echo thematically. We’re being shown Shevek from all around, and his motivations and intentions. We’re seeing his Life, on both planets, his loves, his work, his politics. Structurally, this is a helix, with the action running towards and away from Shevek’s decision, in the penultimate chapter, to go to Urras, and then on beyond that to his return. (“True journey is return.”) It’s an escalating spiral.

This spiral structure isn’t unknown in SF—Iain Banks used it in Use of Weapons and Ken MacLeod used it in The Stone Canal. But both of those are nineties books, and The Dispossessed is 1974. It isn’t a commonplace structure even now and it was very unusual when Le Guin chose it. Outside SF I can think of more examples, but mostly when there’s a present day thread and a past thread, it concerns a mystery in the past, not the wholeness of a life.

Shevek’s work is physics, and specifically he is attempting to reconcile the theories of Sequence and Simultaneity to come up with an overarching theory of space and time. His theories are extensively discussed and are a major part of the plot, though we never get any details or equations. Le Guin cleverly creates the illusion that we understand the theories, or at least the problems, by use of analogy and by talking about a lot of things around them. She references the Terran physicist “Ainsetain” and makes us realise ourselves as aliens for a moment.

It’s interesting that she specifically uses Einstein. This is a book about two worlds and their relationship. The Hainish and the Terrans are mentioned from time to time, but we don’t see them and their promise of the wider universe until the very end.

The really clever thing about the structure is that by structuring the book as a spiral with events running the way they do, the structure of the book itself, the experience of reading it serves as an illustration of the cycles and spirals and sequences of time and space, and of Shevek’s theories. In the end when Shevek gives his theory to everyone, to all the worlds, and can therefore return to his own flawed utopia, he has widened the pattern, taken it out a step, it’s not just Urras and Anarres in their tidal dance, it’s the rest of the universe as well, and Shevek’s ansible will allow instant communication across the distances light crawls. He is freed to go home and to go on, and the book is freed to end with an opening out of possibilities.

And that’s the kind of book I never get tired of.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two poetry collections and nine novels, most recently Among Others, and if you liked this post you will like it. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.