Remember these immortal words: The Lorax made $70 million dollars in its opening weekend.

Yes, you read that correctly. $70 million. It has already made back its budget, which means we can probably expect a sequel somewhere down the line. The orange’n’moustached marketing gambit has been the focus of general derision for a while now, but it seems to have done its job. The Lorax selling SUVs and diapers, judging reality TV, and telling people to turn off their cellphones in rhyme has culminated in box office platinum.

Who else feels indescribable rage on behalf of Theodor Seuss Geisel?

Because we all know this is not the first time Hollywood has taken the lessons and whimsy of a great storyteller, and pared his universe down to questionable humor and altered morals. The Lorax is the fourth attempt to bring Seuss to the screen, and the movie industry remains unapologetic for what they’ve shown to families all over the world, how they’ve mutated classic children’s literature with little-to-no compunction. And the worst part is, it’s working for them. So it looks like we can expect more of this ilk. To think it all began with….

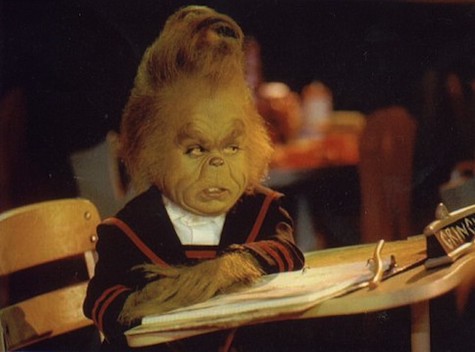

How the Grinch Stole Christmas has been a bedtime staple since we first began to bemoan the commercialization of the holiday. (Hint: it was long before you had to wake up at 2 AM to do Black Friday shopping.) A simple tale about a cruel creature who misunderstood what made Christmas special. It became a cartoon in 1966, read word for word by the mighty Boris Karloff, with music to match. And then Hollywood got their hands on it 2000, and we were given the live action treatment.

It ended up being the second highest grossing Christmas movie of all time. To this day, people seem widely divided over this first attempt of Seuss-on-screen: some enjoy Jim Carrey as the Grinch, others can’t stand him. Some appreciate that it was not rendered as a cartoon, but the Who prosthetics were not for everyone. But let’s forget the look or the talent, or even the cover of “You’re a Mean One, Mr. Grinch” by Carrey himself. The length of a motion picture demands additions to such an direct piece of prose, and add they did. It resulted in a flashback where the audience finds that the Whos had teased and tormented the tiny Grinch as a boy, the real reason for his animosity and shrunken heart.

Nice one, Hollywood. It couldn’t just be someone learning about love and family and kindness, oh no, you just had to turn it into a redemption story on top of everything. It’s not the first time studios have been responsible for that very specific decision, but it’s always depressing when it presents its ugly mug in a story that’s dear to your heart.

It’s certainly not what Seuss had in mind as the moral of his story. You can guess at his hopes—that the reader would learn along with the Grinch, not blubber over his triumphant return to Who society. You’re meant to come to the realization at the same time that he does; that Christmas is not about toys or lights or candy. You are the Grinch, you have his epiphany. But not this time around. You’re too busy paying attention to all those nasty Whos laughing at a poor little green kid.

2003 brought us The Cat in the Hat, another live-action Seuss starring Mike Myers. Because Cat is decidedly simpler than Grinch, a lot more story-padding went down. This led to the awkward decision to have the kids and the Cat followed around by their neighbor, Larry, some creep who’s trying to marry their mother for her money. The older-than-earthworms-in-dirt scenario is more than out of place in such an unguarded tale of play; it derails the film entirely. We get some tasteless innuendo and off-color humor for our trouble, and we also have to contend with a seemingly random character twist: the boy (now named Conrad as he had no name in the book), is not equally distressed with his sister at the Cat’s shenanigans. He’s a great big troublemaker who forces sister Sally to be the bossy, polished angel. Because boys are like that—it’s girl who are made of sugar, spice, and everything nice, didn’t you know?

Since when has Dr. Seuss ever had any room for tired gender commentary like that?

Throw in one unbearable original song and one Razzie Award (Worst Excuse for an Actual Movie—All Concept/No Content), and this film set a brand new standard for adapting Seuss. No taste required. Luckily, critics and moviegoers alike called The Cat in the Hat out for exactly what it was, and it only made its budget back due to the international box office. But there were still plans for a sequel until Seuss’s widow withheld the rights.

It was five years until Horton Hears a Who! made its way onto big screens. And while many were likely pleased that the use of CGI allowed for book-perfect looking Whos and jungle friends, the film still fell on its face in terms of holding true to the spirit of Seuss’s work. Again the need for plot-padding led to a betrayal of the material: Horton’s plight is all the cause of Sour Kangaroo’s conniving and vicious personality, overplayed to give the story a truly proper villain.

The Mayor of Whoville is blessed with 97 children; one, his only son, manages to save the day by using a special horn to finally break the sound barrier so the jungle animals can hear the Whos. The Mayor’s 96 daughters? Oh, right, they do absolutely nothing. I’m sorry, let me repeat that: there are 96 females in this film who serve no function for the story whatsoever. And then, because everyone is friends by the end, the film closes on a heartfelt rendition of “Can’t Fight This Feeling.”

Because nothing says “I believe that all people should be treated with care and respect” like capping your journey off with a little R.E.O. Speedwagon.

Even discounting how the filmmaker’s felt the need to turn the Whos’ quest for survival into a father-son relationship salvaged, even ignoring how badly women come off in the movie for no reason at all (which is sort of impossible to do), there is something very wrong in Whoville.

Which brings us to The Lorax.

While conservatives and liberals alike are already lodging the complaint that the film is too preachy on the environmentalism front, everyone who cares about the integrity of Seuss’s work is feeling let down for a plethora of reasons that have nothing to do with nature. Nevermind the ad campaigns that have The Lorax selling you everything from pancakes to printers to hotel rooms. How about making fun of the prose? As David Edelstein points out in his NPR review:

Early on, a character not in the book, Audrey, voiced by Taylor Swift, tells lovelorn 12-year-old Ted, voiced by Zac Efron, that once, nearby their now paved-over town, there were truffula trees: “The touch of their tufts was much softer than silk, and they had the sweet smell of fresh butterfly milk”—and Ted says, “Wow, what does that even mean?” and Audrey says, “I know, right?”

One of the more boggling aspects of The Lorax film is its choice to put a kid romance at its center; the presence of Zac Effron and Taylor Swift, clearly meant to pack a certain demographic into the seats, is doing something far more damaging to the story than good—it is taking a tale that is meant for everyone at every age, and turning it into something painfully dated and aimed directly at tweens. Does romance help The Lorax? Well, it does tell boys and girls something very valuable… that having curiosity about the world around you doesn’t have much merit. Learning because you have a crush on someone on the other hand, that’s the right way to think.

Why do Audrey and Ted have to seem so modern? The world they occupy in the film is quite close to our own, in fact, which makes no sense at all. Dr. Seuss always retained a fable-like quality that made the work utterly timeless, even when he was making comments on timely material (like post-war occupied Japan and Cold War escalation). Nothing about these films should be so easily recognized.

Then there’s the oh-so impressive addition of a single villain, Mr. O’Hare, the man who doesn’t want the forests back so he can continue selling bottled air to the community. Because we all know that the destruction of the environment is just the fault of one or two greedy businessmen. We’re not all responsible for the state of the earth. We don’t all have the power to make a difference in the world around is.

And Dr. Seuss was certainly not trying to tell us that:

Unless someone like you cares a whole awful lot,

nothing is going to get better. It’s not.

That’s you, by the way. Mr. O’Hare and his bottled air have got nothing to do with it.

So how much care does Hollywood really put into these stories? I suppose it can be summed up easily with this little gem: A short while back, there was a petition on Change.org from a class of fourth graders: they went to The Lorax film website and found absolutely no mention of trees (or the environment) whatsoever. Their rally to arms led Universal Studios to sit up and take notice—they changed the website to include tips on how to help the planet.

But it took a class of ten-year-olds to remind them of what they were selling. You’ve got to hand it to the good doctor; even in this day and age, he is still reaching his target audience before tinsel town has the chance to lure them away.

Emmet Asher-Perrin just hopes they never make The Butter Battle movie. You can bug her on Twitter and read more of her work here and elsewhere.