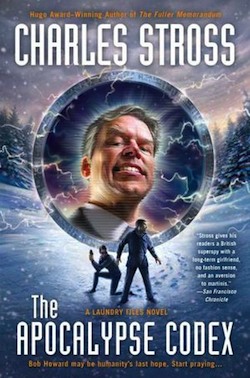

The Apocalypse Codex, fourth book in Charles Stross’s ongoing “Laundry Files” series, picks up with Bob Howard after the events of The Fuller Memorandum (reviewed by Arachne Jericho here): recovering from physical and mental trauma, returning to work for light duty. Except, it doesn’t seem that light duty is in Bob’s cards—no matter how much he wishes it was.

As the flap copy says, “For outstanding heroism in the field (despite himself), computational demonologist Bob Howard is on the fast track for promotion to management within the Laundry, the supersecret British government agency tasked with defending the realm from occult threats. Assigned to External Assets, Bob discovers the company (unofficially) employs freelance agents to deal with sensitive situations that may embarrass Queen and Country.”

When these freelance agents (and Bob) are set to investigate Ray Schiller, an American televangelist with uncanny abilities who’s getting too close to the Prime Minister, a political incident becomes the least of his worries—because there’s more than preaching going on at Schiller’s ministry.

The first thing worth noting is that, if you haven’t read the prior books, this is not the place to start. Stross’s series is not the episodic sort, where you can pick it up at whatever point you like—begin at the beginning, and the significant evolution of the characters and world in each book will reward you. Also, you’ll know what’s going on, which is sort of vital, I would think.

The second thing is that I love this series. I find it uproariously fun and engaging, from the world-building to the well-fleshed out characters to the underpinnings of real tragedy and consequence layered beneath the mysteries, action, and Lovecraftian horrors. Stross is also playing with cliché, genre conventions, and reader expectations in these books with an understated panache that brings me a whole different kind of reading pleasure. In a genre overrun by predictable police procedurals and the like, the Laundry Files books genuinely stand out: clever, not merely wish-fulfillment fantasy, filled with allusions, cues, and tips-of-the-hat to other texts, and written with clear, sharp, eminently amusing prose. Plus, they justify their usage of first person—these books are framed as Howard’s reports and memoirs for the Laundry, using narrative tactics as if Howard himself is literally writing these confidential reports and we are fellows reading them on the job. Oh, and the books are populated with women and queer folks who are fully realized, authentic characters—hell, Bob is married to one of them—but this is usual from Charles Stross. (The second book, for example, revolves around a hilarious gender-aware parody of James Bond.)

On these notes and more, The Apocalypse Codex does not disappoint.

I’m tempted to say simply, “If you like these books, this is a book you will like,” because it is. The same pleasures to be found in the other books are all present and accounted for here. Which is not to say that it’s a rehash—nothing of the sort; there is a great deal of fresh evolution in character and universe both, here. The major danger in most long-running urban/contemporary fantasy series is stagnation: characters who remain the same, a world with no new surprises, episodic adventures with nothing authentically at risk, et cetera. Stross has yet to have an issue with this sort of stagnation, and after four books that have intrigued me, satisfied me, and provoked an abiding curiosity in me for more, more, more, I believe it’s safe to say that he likely won’t any time soon.

The Apocalypse Codex keeps fresh by uprooting Bob from his usual circumstances, compatriots, and safety nets. While Mo, Angleton, and the familiar crew are all at least briefly present, the majority of the novel takes place in America with the “freelance agents” (who aren’t quite that at all, it turns out) Persephone Hazard and Johnny McTavish. The antagonists, Raymond Schiller and his Golden Promise Ministry, are an eerily evocative mix of real-life megachurch doctrine and the particular kind of madness that the intensely faithful are vulnerable to in the Laundry universe. After all, as Bob says, there’s One True Religion, and its gods are nothing we can know or understand. Mostly, they want to eat us, minds first. The touch that I found interesting is in Stross’s handling of the “evil evangelist” trope; Schiller genuinely believes, rather than being a cackling monolith of intentional evil. (This is not the first time Stross has played with a genre trope in this series—The Atrocity Archives has space Nazis, The Jennifer Morgue is a James Bond pastiche, et cetera—and each time, his angle on the usual is a humorous sort of commentary.) While Schiller is disturbing, and his ministry moreso, the motivations are all legitimate, rather than Bond-villain-esque. One of Persephone’s misconceptions is that Schiller must be after money or power in the beginning; Johnny thinks otherwise, as he has some personal experience with this kind of “church.”

Speaking of, the two new characters were quite the blast to read, particularly Persephone. As the books generally take place wholly from Bob’s angle, his introduction of other peoples’ reports to his own to flesh out the full story is a new and enjoyable tactic. Told in third-person as related to him, the sections that give us Persephone and Johnny’s stories allow for a greater narrative diversity—and an outside view of Bob than we don’t generally see. Persephone’s development, and her explicit interest in and sympathy for the suffering of other women, intrigued me, and gave a different angle than usual in this series. Bob is a great guy—loves his wife, isn’t a sexist asshole, etc.—but he’s still a guy, with guy-thoughts; Persephone’s narrative balances this nicely. There are a few other third-person sections, such as those with Angleton and Bob’s temporary new boss, but I’m attempting to avoid spoilers and will say no more of them.

Though on that thread, as spoiler-free as possible, I will say that one of my favorite parts of The Apocalypse Codex was the big revelation about the structure, intentions, and deep background of the Laundry, revising our (and Bob’s) previous ideas about the organization immensely. And, of course, the ending, which provoked the sort of thrill and “oh, next book please!” that it’s remarkably difficult to get from me.

There are a few minor missteps—for example, the basic explanation of CASE NIGHTMARE GREEN appears several times, and while the phrasing is always a mixture of humor and horror, the repetition wears a bit. (Especially considering the number of times it’s also defined in the other books.) As a whole, however, the book flows with fewer hitches than The Fuller Memorandum, which, as Jericho noted, had a few problems balancing the amusing bureaucracy with the action. The Apocalypse Codex is fast-moving, the bureaucratic shenanigans integral to and well-balanced with the investigative plot—and, frankly, just as engaging once we get to the high-level revelations and insight into the operational mechanics of Mahogany Row.

The Apocalypse Codex is a good book that’s part of a deeply enjoyable series—a pleasant and entertaining way to spend the day’s reading.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. Also, comics. She can be found on Twitter or her website.