“A Matter of Time”

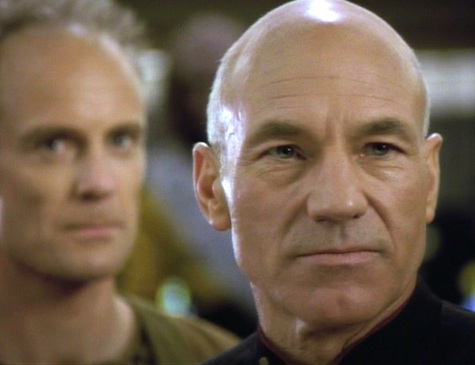

Written by Rick Berman

Directed by Paul Lynch

Season 5, Episode 9

Production episode 40275-209

Original air date: November 18, 1991

Stardate: 45349.1

Captain’s Log: The Enterprise is en route to Penthara IV to help counteract the devastation on that world following an asteroid strike. However, Worf has detected a time-space distortion and an object that hadn’t been there previously. They stop briefly to investigate, and find a tiny ship that is impervious to sensors. After Worf hails them, he tells Picard that the message is a request to move over. Picard says the Enterprise isn’t moving anywhere, but then Worf clarifies that the request is for the captain to move over. He walks toward Worf to ask what the hell they’re on about, and then a tall figure materializes where Picard was standing.

He identifies himself as Professor Berlinghoff Rasmussen, a historian from the twenty-sixth century, and he’s traveled back three hundred years in order to witness historical events. While explaining to Picard that he can’t give specifics as to why he’s there, he does check out the ready room—apparently, his Shakespeare book was believed to be on his desk rather than the end table, and Rasmussen had apparently guessed correctly about the distance from the door to the wall.

Rasmussen wants to give the senior staff questionnaires. He is still not forthcoming with specifics—though he continues to ask silly questions, like if Worf usually sits on that side of the table—but he does confirm that he came to this day on purpose.

The staff is skeptical, but he is human, and he is in a ship that’s like nothing they’ve ever seen, which came out of temporal distortion. Picard says he’s examined his credentials, and everything seems in order. (Of course, Picard has no idea what his credentials should look like, so that’s kind of meaningless, but whatever.)

The Enterprise arrives at Penthara—where it seems to be a local law that you must wear an ugly gray jumpsuit with silver trim in order to live there—where Picard and La Forge discuss options with Dr. Moseley. They can use drilling phasers to release pockets of carbon dioxide. Moseley comments on the irony of them creating a greenhouse gas effect that they’d spent decades trying to avoid. But it’s necessary for them to keep as much heat in as possible.

Rasmussen joins Riker, Crusher, and a very reluctant Worf in Ten-Forward. The time traveler provides them with their questionnaires, and Riker asks why there are no other records of time-travelling historians. Rasmussen says that he and a colleague went to the twenty-second century just recently. Crusher immediately asks if he saw surgical masks and gloves, since that was before quarantine fields. Rasmussen is amused by what different people consider important, and he then asks Riker what he thinks the most important invention of the past couple hundred years was. He says the warp coil. Worf says the phaser.

Then Rasmussen heads to engineering to give Data and La Forge their questionnaires. All along, Rasmussen makes oblique comments that make people wonder why he’s here for this mission. At one point, Rasmussen surreptitiously pockets a padd.

The Enterprise starts drilling. It does the trick—the temperatures stop dropping, and in a couple of equatorial regions it’s even gone up. Now Penthara has time.

Later, Rasmussen goes to sickbay to ask Crusher about a neural stimulator, and she gives him one.

A discussion on the bridge about Rasmussen’s questionnaires is interrupted by an alarm: there are earthquakes and volcanic activity on the planet. The Enterprise overestimated the geologic stability of the drill sites, and releasing the carbon dioxide has caused the mantle to collapse. Worse, the volcanic ash will compound the existing problem with the debris from the asteroid.

Rasmussen visits Data in his quarters, asking him for schematics, claiming that very little of Noonien Soong’s work survived to the twenty-sixth century. (He also comments that he should have told Data to limit himself on his questionnaire to 50,000 words or less, to which Data replies, “You did ask me to be thorough.”) While the android speaks with La Forge on the surface, Rasmussen palms a tricorder.

The particles in the atmosphere are charged. La Forge and Data have a plan that, if it works, will save the planet by using the phasers to convert those charged particles into plasma, and then use the Enterprise shields to absorb that plasma and discharge it, thus clearing the atmosphere. But if they’re off by even a little bit, they’ll burn off the planet’s atmosphere and all twenty million people (and all other life on the planet) will die.

Picard is agonizing over the plan while waiting for the colony leaders’ decision, and he summons Rasmussen to his ready room. Picard is stuck on the horns of a dilemma. On the one hand, asking Rasmussen for the outcome violates everything he believes in, all his training as a Starfleet officer—but he now has twenty million reasons to change his mind. Rasmussen, however, isn’t budging in his willingness to tell Picard what happens—which Picard finds appalling, given the possible death count. But Rasmussen can’t risk his own history being altered—and besides, all of these people are long dead from his perspective.

They go back and forth, until Riker interrupts, saying that conditions are the best they’re going to be. Rasmussen, for the first time, sounds sincere when he says he can’t help Picard and that he’s sorry.

They go to the bridge, where Rasmussen realizes that Picard had already decided to try, even without his help. Picard assures Rasmussen that he did help—his refusal to assist reminded Picard of the importance of freedom of choice. And he chooses to act rather than play it safe. La Forge feels the same way—he chooses to remain on the surface, despite the risk. When Picard says there’s no guarantee it will work, La Forge points out that there’s no guarantee it’ll fail, either.

The plan works, the planet’s saved, and Rasmussen announces that it’s time to go. With a final comment that Riker is taller than he expected, he buggers off.

Arriving at the shuttle bay, the crew refuses to let Rasmussen onto the ship until they can search it for some objects that have gone missing. Rasmussen assures them that he’s not here to forage for relics, but Worf assures him that, if he doesn’t open the ship, Worf will do it with explosives, if necessary.

Rasmussen agrees—but only if Data accompanies him alone inside ship, since he won’t divulge what he sees if Picard orders him to do so.

They enter the ship, and Data finds a tray filled with items from the Enterprise. Data points out that they don’t belong to him; Rasmussen admits that the phaser he’s now holding on Data doesn’t, either. Turns out, he’s not from the twenty-sixth century, he’s from the twenty-second. His ship is indeed from the twenty-sixth—”At least, that’s what the poor fella said”—but Rasmussen stole it. A dismally inept inventor in his own time, he has come to the future in order to swipe some items and “invent” about one a year or so, thus making his fortune.

However, the phaser doesn’t work. Once Rasmussen opened the door, the Enterprise was able to scan the ship’s interior and deactivate anything belonging to the ship inside—including the phaser. Data brings him back outside (“I assume your handprint will open this door whether you are conscious or not”), and Worf takes him into custody after retrieving all the items. The ship itself—which was on an autotimer—disappears, to Rasmussen’s horror.

Can’t We Just Reverse the Polarity?: Rasmussen’s stolen ship is made of a plasticized tritanium mesh, which is like nothing on record. (“At least until now,” La Forge adds.)

Thank You, Counselor Obvious: Troi doesn’t trust Rasmussen, knowing that he’s hiding something—which is natural given that he needs to hide things about the future for his cover, but still…

There is No Honor in Being Pummeled: Worf is cranky about Rasmussen from jump. He also claims to really hate questionnaires. He must’ve been a barrel of laughs at the Academy.

If I Only Had a Brain…: Rasmussen says Data is like the Model T of androids. Data corrects him by saying a more apt analogy would be the Model A, since he was Dr. Soong’s revised prototype.

He also listens to four pieces of music at once, but can listen to up to a hundred. He seems oddly surprised that Rasmussen has trouble talking when he does that.

No Sex, Please, We’re Starfleet: Rasmussen flirts with Crusher, who seems to be okay with it right up until he gets more aggressive with it, at which point she reminds him that she could be his great-great-great-great-great-great-grandmother.

In the Driver’s Seat: This is the first of five appearances of Ensign Felton at conn, an officer so distinctive that I totally forgot she existed until I watched this episode again.

I Believe I Said That: “What if one of those lives I save down there is a child who grows up to be the next Adolf Hitler or Khan Singh? Every first-year philosophy student has been asked that question since the earliest wormholes were discovered.”

Picard arguing with Rasmussen over what to do.

Welcome Aboard. Matt Frewer is the big guest in this one, best known in genre circles at the time as the both a reporter and a wacky computer avatar in the short-lived cult hit The Max Headroom Show (the latter role also served as a Coke spokesperson for a while, and those ads were probably more popular than the TV show, more’s the pity). Frewer also starred in the even-more-tragically-short-lived Doctor! Doctor! and has actually carved out an impressive career as a character actor. While he’s best known for his wacky roles, like Taggart on Eureka and the White Knight in the SyFy miniseries Alice, he also has done some stellar turns on Canadian television, most particularly the serial killer Larry Williams on a two-part DaVinci’s Inquest (for which he was nominated for a Gemini Award, the Canadian equivalent of the Emmys) and the starring role of semi-ethical cop Ted Altman in Intelligence.

Trivial Matters: The role of Rasmussen was originally intended for Robin Williams, but his filming schedule for the movie Hook kept him from doing so. Both Frewer and Williams were known for ad-libbing in their seminal TV roles—Williams in Mork and Mindy, Frewer in Max Headroom. (Given how Hook came out, Williams might’ve been better off with this role.)

This episode would be referenced by Odo in the Deep Space Nine episode “Bar Association” when he wants to give Worf a hard time about all the security breaches on the Enterprise.

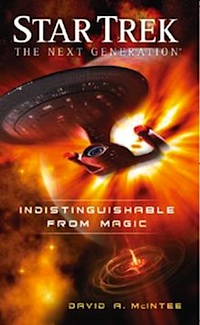

After serving his prison sentence, Rasmussen shows up for a big poker tournament on Deep Space 9 in the novel The Big Game by “Sandy Schofield” (a pseudonym for Kristine Kathryn Rusch and big-time poker enthusiast Dean Wesley Smith), and also played a major role in David A. McIntee’s Indistinguishable from Magic. He also appears in J.R. Rasmussen’s very metafictiony short story “Research” in the Strange New Worlds II anthology.

Make it So: “We should be on our way back to a place called New Jersey.” I really wanted to be excited about this episode when it first aired because I’ve been a huge fan of Matt Frewer’s since his Max Headroom days, and have continued to follow his career through good and bad (he was, quite possibly, the worst Sherlock Holmes ever).

Sadly, this episode doesn’t make nearly as much use of Frewer’s talents as it should. He’s not manic enough to be fun, not subtle enough to be convincing. Picard’s trust of him seems off somehow, like he’s going along with it because the script told him to, though at least Worf and Troi maintain their skepticism. It’s cute to see that few can resist asking him about the future, not even Data, and there are some other fun things, but ultimately the episode just feels meaningless.

Nowhere is that more apparent than in the very well-scripted scene in Picard’s ready room where Picard tries every rhetorical trick in the book to cajole assistance from Rasmussen. That’s a scene that doesn’t work after the first time you see it, because when you know that Rasmussen’s a con man, the scene utterly deflates, because there’s no moral dilemma for Rasmussen. What should be an interesting discussion about the philosophical and ethical implications of time travel instead becomes Picard wasting his time.

Admittedly, it takes talent to waste a scene that has two actors of the caliber of Frewer and Sir Patrick Stewart, but that’s not the kind of talent you actually want to see creating TV shows.

Warp factor rating: 4

Keith R.A. DeCandido wonders what happened to Rasmussen’s time machine. Who found it when it went back to the twenty-second century?

Just a note. Rasmussen plays a HUGE role in the very good stand-alone novel from David McIntee Indistinguishable From Magic. McIntee does a great job with the character making him a man out of time, but with still something to contribute.

I was just about to mention Indistinguishable from Magic myself. The novel also explains what happened to “the poor fellow” that owned the timeship and how it came into Rasmussen’s possession.

I find this an enjoyable enough episode, and Frewer is fairly good in it. I don’t think I would’ve liked Williams in the role. If anything, it would’ve worked better with less of a comic actor and more of a cool, calculating type who could’ve become malevolent in the final reveal (which might’ve implied a more sinister fate for “the poor fellow”).

And I don’t think “the scene doesn’t work once you know the secret” is a totally valid criticism, because the same could be said about a lot of murder mysteries, movies like The Sixth Sense, etc. It’s pretty natural to write a story with the assumption that your audience is experiencing it for the first time. And in repeat viewings there can be value in seeing the underlying meaning that was hidden before, and while this isn’t on the same level as The Sixth Sense by a long shot, at least knowing the truth casts Rasmussen’s seemingly sincere apology to Picard in a new light. He’s sorry he can’t help, because he just doesn’t know what’s going to happen.

Dont forget : indistinguishable from magic which features rasmussen in the first half of the novel.

And i should always read the comments before making my own because than my commentd wouldnt be so redundant. Haha.

My general feeling on this is MEH. The twist of the time travelling guy from the past is pretty nifty, but that’s about it. Otherwise it’s 42 minutes wasted on a kleptomaniac con man. There is never a feeling like the planet is going to be destroyed so it’s just a matter of what is Rasmussen’s secret is, and when it’s revealed… he’s just this guy. Had Rasmussen been malevolent in some way then we’d feel happy that he had been defeated, but in the end, you just sort of end up feeling bad for him. Overall, the bad guy is blah, the b-plot is blah, and the episode is just blah.

This episode never worked for me mostly because the character of Rasmussen doesn’t work for me. Knowing that the role was written for Robin Williams actually makes a certain amount of sense. Rasmussen had that same sort of maniac-fiddling-with-everything-can’t-ever-shut-up energy that Williams has in pretty much all of his roles that is supposed to be amusing but I just find incredibly irritating.

Overall, I just couldn’t figure out how anyone could possibly believe that Rasmussen was actually a historian come back to witness important events (and not change them), when he seemed like his actual goal was to insert his nose into everything and annoy the crew into throwing him out an airlock. It would be like someone coming back to witness D-Day by barging into Eisenhower’s headquarters and asking him “And what are you thinking?” every five minutes. That couldn’t possibly affect his ability to command.

The nice thing about “Indistinguishable From Magic” is that it portrays Rasmussen in kind of a tragic light. Sure, he has a temper and know how to hold a grudge, but he honestly didn’t mean to harm the poor guy who came back in time to the 22nd century. Rasmussen tried to pull his con on him, didn’t know that the guy had a medical condition, and everything went pear shaped.

Though he also seems more than willing to switch sides during a fight to serve his best interests, so I kind of equate him to Vash to an extent. Though she is too a character who didn’t work entirely well either (in my opinion).

Also, didn’t he sacrifice himself for Geordi and Scotty at the end of “IFM” as well? McIntee wrote him with a lot more levels than displayed here, I think.

So apparently Rasmussen was in David’s Indinstinguishable from Magic. *laughs* I’ve edited the post….

—Keith R.A. DeCandido

Don’t know if anyone had the same reaction to the pictures of Matt Frewer as I did…I knew I recognized him from somewhere other than the roles described above. It finally hit me – he was “Trash Can Man” in the TV Miniseries adaptation of Stephen King’s “The Stand”.

I found this episode kind of annoying because I wanted Frewer’s character to be more fun and a bit more manic than he was portrayed. I was unsurprised by the reveal that Frewer was a criminal it was sort of expected by the end; I was a better historian as a sophmore in college. I did like when he asked Picard to move so he could transport to the bridge.

I always assumed the Max Headroom show came about because of the popularity of the Coke ads. I may have to check it out.

Disappointed by the lack of regard for Ensign Felton. I always thought she was the cutest of all the helm ensigns, and by surviving 5 episodes she must hold the Star Trek Longevity Record for non-main cast Starfleet ensigns.

It’s worth noting that American Max Headroom series is based on a one-off for British television that in itself was borrowed the Max Headroom character for a talk show series he hosted.

If you, ahem, check the nets for it, it’s worth watching as it’s got a bit of actor overlap with the American version but there are some differences.

And Max actually did a number of adds for various markets ranging from theUK to Australia.

Some weaknesses in this episode – not the which is a rubbish B-plot on the planet – but for me, the fabulous ready room scene where Rasmussen and Picard knock seven bells out of one another (rhetorically) makes up for it. One of the finest two-hander scenes the series ever produced.

Am I the only one in the world who kinda wishes that Rasmussen would have actually been a legitimate future time traveling historian? I mean, I guess we did see what would eventually become what ST: VOY would refer to as the Temporal Prime Directive being used here, even though in reality, it’s just hogwash cause he really didn’t know what was going on unless he’d done some research before actually coming to Enterprise. I think, as powerful as the scene with Rasmussen and Picard in the ready room was, it would have been much more so if he’d been a real scientist.

At least to me.

leandar: Yes, that would’ve been more interesting, or at least given that scene more weight.

—Keith R.A. DeCandido

This is a mediocre episode that I like anyways. I love seeing the time travel tables get turned on the TNG crew. I like Matt Frewer even though the character’s kind of a non-starter. In fact, he’s too likable in the role – it makes the ending really bleak.

Glad to see I’m not the only one who remembers Doctor, Doctor. That show deserves to be on DVD.

Mr. Decandido,

I’ll admit that I am honestly just a casual reader of tor.com, but since TNG was a big thing in my childhood, I’ve been at least skimming every review you’ve written…and I have to ask…do you actually like this show? I was just thinking to myself as I read that I could probably count on one hand how many eps you’ve given over a 5 in your review. Now, I’m sure that’s an exaggeration, but I’d bet it’s closer to true than not.

I certainly won’t argue the point that most eps haven’t aged well, but for what it’s worth, as a casual reader…I have to wonder. You obviously know tons about Star Trek. I’ve even read one or two of your books, but you’ve got to admit you’re pretty hard on these shows.

For what it’s worth.

matt s: “Now, I’m sure that’s an exaggeration, but I’d bet it’s closer to true than not.” –

And you would lose that bet.

Looking at the numbers:

There have been ~104 reviews (I may have missed one) – out of those, 55 have been rated 5 and lower, while 49 have been rated 6 and up. If you take 5 as the level of “decent episode”, then 61 have been rated 5 or higher, with 43 rated 4 or lower. If you can count that many on one hand, you might need to see a surgeon about those extra fingers… :)

The average rating is ~5.4 (if you throw out the gadawful clip show Shades of Gray which got a 0, it gets to ~5.5). You also have to remember that the first two seasons were notoriously top-heavy with bad-to-mediocre episodes, so at this point the numbers are going to be a little depressed. It would not suprise me by the end of the rewatch for the average to get in the 6 range.

So am I the only one who read the review and thought it would have been fun if Rasmussen had arrived in a police box?

:-)

First comment. Long.

People who want to accuse the reviewer of hating the show should pick another episode to comment on.

Wasn’t this as bad as Datalore, without the redeeming backstory info? The plot required the crew to trust a random new person far beyond the level they should have even been allowed to, based on flimsy claims. Even though Picard says he believes Rasmussen is a historian from the future, he didn’t say the crew should let him walk all over them. Riker even lets him sit in his chair, just making a face. Again, we see top Starfleet officers being skeptical and then not acting on that skepticism.

Rasmussen even acts like a confidence man, and we know they know other devious types such as the Ferengi and Kivas Fajo. “He is human — the medical scan shows that.” Oh, then he must be a historian from the future.

From the Rasmussen point of view, how could he possibly think that items like phasers disappearing on a starship wouldn’t go noticed? He even steals a tricorder from Data’s quarters, someone not likely to think he just misplaced it.

Worse is the planet-disaster subplot. The scenes where they fix the planet achieve results so fast it’s comical. The greenhouse effect takes more than 15 seconds to work. Also, the stakes are too damn high: can we really believe that Picard could authorize a course that might instantly kill 20 million people, when the alternative gives them weeks to find another solution? Shouldn’t there be a Federation-wide relief effort, airlifting (or equivalent) winter supplies until an evacuation can be arranged? There is even a touching moment where Picard wants to beam Geordie up. My chief engineer has come up with a solution that might kill 20 million instantly, better not let him be among them.

The intersection of the both disastrous plots comes when they leave from the Picard-Rasmussen radio room scene directly to the bridge saving-the-planet scene, which ends with Picard nodding to Worf, which presumably set the plan to confront Rasmussen into motion, without indicating what tipped him off. We never find out, because the only thing Picard says later is that items were missing.

The episode might be redeemed by the look on Rasmussen’s face when Picard tells him he’s being shipped back to earth as a prisoner and object of study. At least until you think about the time machine going back to 22nd century New Jersey. Overall, barely watchable.

I wondered why the crew didn’t test Rasmussen (before giving him access to files) by lying about their recent past and seeing how he reacted to it, e.g., “Can you help us out since we lost half the fleet in our total war with the Romulans, and Earth was occupied last month, and the entire planet Vulcan was destroyed by a giant mining ship, etc …?” If Rasmussen played along, they’d know he was a fake.

This is my second time seeing this episode and I think I liked it less this time, although not for the reason you mention (realizing Rasmussen doesn’t actually know what happened) I do still think that scene is pretty interesting from Picard’s perspective.

I think I just picked up more of the inconsistencies in his story – if he really WAS a historian, his being there would be altering history just by being here. So it seems like it should be way more obvious that he’s not.

Also, one thing that has come to mind on numerous episodes – why doesn’t the Federation have some kind of speedy planet evacuation plan? It seems like there are lots of situations where they would be saved from having to make these kinds of decisions of they had some kind of efficient way of getting all the colonists off the planet, perhaps on some kind of temporary mobile space station, figuring out what to do, etc. These kind of planetery emergencies seem to happen often enough to warrant it!

What is with the Hook bashing! I love that movie! Probably my favorite Robin Williams role :) Granted, I was an adolescent when it came out, but I recently bought a used copy and I still love it :)

I actually kind of liked Frewer’s performance (even though that whole manic energy humor is not typically my cup of tea) and I must admit that the first time I saw this episode, I was rather engaged. I knew that he had to be lying, but I was interested to see how it would all unfold. As others have commented, the reveal was a letdown, and I thought they could have come up with something a bit more interesting (like, what if he WASN’T lying??).

I couldn’t believe Dr. Crusher was turned on by this doofus. Come on, Bev, use your gut instinct!

Hook IS a great movie, by the way, and I absolutely concur that one’s

opinion of it directly correlates to age upon initial viewing. It was a

childhood favorite of mine, but I think it made my mother the hardcore Williams hater that she is today :)

Nice to see that everyone who mentioned IFM seems to have liked it!

This is kind of a frustrating episode, which should be better than it turned out. As for Frewer being the worst ever Holmes, allow me to mention Roger Moore’s attempt at the role…

David: haven’t actually seen Moore’s Holmes. I saw Frewer’s. Gack.

Then again, Tom Baker’s was pretty dire, too….

And sorry for not including IFM in the first pass, but the edit function has saved my ass. Pretty much anything published from 2009 forward, I’m only going to know about if they’re in Memory Alpha and/or Memory Beta.

—Keith R.A. DeCandido

I like this episode more than it’s actually worth, I suppose.

One criticism I see above is “Frewer not allowed to be as manic as usual.” Well, in that case, I suggest you watch Jeremiah Johnson and then tell me which guest star isn’t living up to his maniacal past.

No worries, Keith.

I did see Tom Baker’s Holmes when it first aired, but remember absolutely nothing of it! Frewer is certainly dire in the role, but Sir Rog is still the worst in my eyes.

It’s on Youtube, FWIW…

Very late reply… I recently saw Baker’s Hound of the Baskervilles on BritBox, and I thought it was okay. Baker’s Holmes is basically just Baker’s Doctor in his most serious mood, but I didn’t have a problem with that, since the characters have a lot in common (and “The Talons of Weng-Chiang” played that up heavily). Although Terence Rigby’s Watson was terrible, a Nigel Bruce-ish dodderer without Bruce’s charm.

Since I don’t see it mentioned here, Frewer also had a pretty big part in the Sci-Fi (Syfy?) mini-series Taken, produced by Steven Spielberg. I’m not sure how well it’s aged, since I only watched it when it first aired in 2002, but I liked it then. It spans nearly a century of alien abductions, sightings, etc.

@22.MB

“and the entire planet Vulcan was destroyed by a giant mining ship, etc …?” —LOLLLL

Thanks for almost getting me fired when I started laughing like a crazy hyena when I read that one!!

Nick

I always liked this episode.. AND Hook! And thanks for the person who pointed out the Stand/Trash Can Man thing… I thought he looked familiar and none of the references in the review were things I was familiar with. I watched The Stand a few months before my TNG rewatch so that is probably why her ang a bell…

@@@@@ 13 – Yes, Max Headroom was huge in the UK before the American series came about. He was created by Annabel Jankel and Rocky Morton, who were kind of media darlings in Britain at the time having been pioneers of the music video industry. They created Max to present a music video show on Channel 4 which became an absolute must-see among the late teens to early twenties audience. Anyone British who was in this age range at the time (including me) would have watched every week and even videoed the shows to rewatch again and again.

It was the success of this show that gave them the chance to make the TV movie telling Max’s backstory, which then led to the US TV series based on the TV movie. Jankel and Morton went on to direct the rather excellent movie DOA, and then unfortunately the rather lousy Super Mario Brothers movie which I think pretty much finished them as far as Hollywood was concerned.

Have to agree with @21. This plot goes from mildly entertaining to ridiculous the moment it decides to spend most of its second half talking about a “solution” to a problem that could easily kill an entire planet’s population (tens of millions of people) without ever considering evacuating anyone… except Geordi.

It’s preposterous. It makes one think back to all the moral dilemmas of “The Ensigns of Command” where all that was at stake was a few thousand people whom the Federation didn’t even know about until that episode. There was all that angst about how they would evacuate the people, etc. Here we have an established colony with tens of millions of people, and Picard’s eager to take a chance that might kill them all?!?

Yes, so we are told, thousands may die in the next few weeks. Why not beam up those who can’t take shelter from the extreme cold, while the plan is considered more carefully? Why not request another ship from the Federation for (hopefully temporary) evacuation of those at risk of dying from the cold? At least until everyone can be sure the plan will work….

Instead, it’s just “Damn the torpedos, full speed ahead!” and if we happen to kill millions of people, oh well, Picard took the time to argue about it with a time traveler, so he’s just “seizing the moment” or something and making a decision.

No, no, no.

This could have been easily fixed with a little extra dialogue considering these options, or considering evacuations in some detail, or… well, any recognition that this episode could easily have ended with Picard making a rash decision to exterminate millions of people.

This episode isn’t just bad. It’s insane.

I disagree that once you know Rasmussen is a fraud that it damages the episode, because the episode is broadcasting that he’s fishy from the moment he arrives. What hurts this story for me is how out of character it seems for Picard to at first trust Rasmussen (what ‘credentials’ could he possibly have checked out?), to allow him to interrogate the crew, to permit him to prance around on the bridge, or to make a plea for information that might change the future.

Imo, another classic “outsider comes onto the Enterprise, is rude to everyone, and then turns out to be evil/a phoney/insane!” episode. You can see it coming a mile away, so it just isn’t interesting. And seriously, does the crew know what locks are? Security checks? No one should be able to waltz onto the bridge like that over and over without clearance. I also agree that the B plot was pretty ridiculous–of course the whole planet isn’t going to die. This really seemed like a 2nd or 1st season episode.

I will give them credit for letting Troi, at least sort of, do her job for once. I really liked that she didn’t trust him, although (oh man, here I go about Troi again) I thought it was rather silly for her to not want to be around him. Follow him and observe. It’s your job to help figure out who he is and whether he’s lying.

Also, @20, I am 100% down for a TNG/Doctor Who crossover. Would be a rare “outsider comes onto the Enterprise, is rude to everyone, turns out to be insane in the best way.”

The seeds for Henry Starling in Voyager’s Future’s End were sown here. It may interest people that Tom Baker was also in the running to play Rasmussen, according to the IMDb.

It would have been a much more interesting episode if there had been a scene in which Rasmussen told members of the crew things that a random stranger wouldn’t know. As it stands, he’s just a conman/fortuneteller, reacting to what people tell him in order to pretend that he has some great knowledge that he doesn’t. How would he know anything about the future? Well, he did murder the owner/pilot of the ship he’s flying, so maybe that ship’s computer has some some of mega historical database on it. I mean, if the damn thing can travel through time, I’m sure by that point information storage will be no big deal, even with massive amounts of data. That would have added to the tension, because right now Rasmussen seems like a conman from the beginning.

They also do a bad job showing him pocketing everything. The trick with Crusher’s device is done much better. And why the hell would Worf’s dagger be valuable 200 years in the past?

I remember when this episode first aired. I really wanted to like it more than I actually did.

I’ve always loved time travel stories, but this one just didn’t quite work for me. I think one problem, to me anyway, was that it seemed blatantly obvious early on that Professor Rasmussen wasn’t who/what he claimed to be. I wasn’t sure what he was really up to, until he was exposed as a con man at the end, but it seemed clear right away that he wasn’t a “historian from the future”.

I don’t know if it’s the way he was written or the way Matt Frewer portrayed the character, but he seemed so shady to me that I found it hard to believe that Captain Picard and the rest of the crew weren’t more suspicious than they were.

The other thing that bothered me, for some reason, is that if Professor Rasmussen hadn’t been so obnoxious and over-the-top, he actually would’ve gotten away with his plan quite easily, doing who knows what damage to the timeline. Nothing the Enterprise (or crew) did was responsible for thwarting him — he did it to himself. Not sure exactly why that bothered me, but it definitely decreased my enjoyment of the episode.

The ending I would have loved is the crew looking him up after the time ship disappeared and discovering he actually was the person who invented several of the things he had stolen. The “oh, shit, now we have to ship this con man back to the past…” would have been priceless.

A bigger issue for me is this – if Rasmussen is actually from the 22nd Century (the past), then how does he know anything about the Enterprise D at all? He seems to recognise Picard and others by name, yet I can’t figure out how he even knew where the Enterprise D would be at this particular place and time in order to meet up with it. I suppose he could have gone further into the future first to find out where to meet the ship, but how he would gain easy access to that information or manage to slip by in an even more futuristic era is a big question.

Apologies if I missed out this explanation in the episode, but I don’t recall this and it’s quite a big gap to fill!

Kensu, no explanation is given but I’ve always assumed that the timepod contained historical records about the Enterprise-D and Rasmussen studied them for weeks before travelling to the 24th Century.

Thanks, GusF – that’s a very good point! Makes perfect sense for a time traveller’s ship to have good records, which would be easy to use to ‘brush up’ on the right time period.

I liked this episode, even though I find Rassmussen a bit annoying at times. What really doesn’t work out though was when Riker asked “why are there no records about time travelling historians?” and Rassmussen is like “because we are so careful”. I beg your pardon? You are anything BUT careful! Yes, of course this is a con, I get that. But would he had played it low a bit more he actually might have got away with his stolen items.

But I still kind of liked his over the top acting. Weird. :D

This is an episode that tries hard, but doesn’t have the firepower to be more than an also-ran. It brings up some fairly heavy thought points on free will and fate, and Picard is put in a dilemma that echoes “Time Squared” in some ways. It doesn’t really come together though. I feel that Rasmussen had to be believable, but he feels phony from the get-go. I think we’re supposed to find him more funny and charming than he is; instead, he generally comes across as overbearing and insufferable. That said, a few scenes are pretty good – with Data in particular, like his annoyance with Data listening to four classical pieces at once.

It’s been beat to death, but I too question what anyone was thinking, and how many procedures were being ignored, to allow a random stranger the run of the ship and to cooperate with his silly assignments. Also, Picard asking him to bend the temporal prime directive, if such a thing exists, begs the question of what an educated and ethical time traveler is doing interacting with the past in the slightest measure.

I wish in so many ways that the immortal Robin Williams had been able to play Rasmussen. Nothing against Matt Frewer, but it seems like RW fell through too late to do much of a re-write. I know big names in Trek don’t always pan out. Still, I have to wonder what kind of humor RW would have brought, and if his more serious side (a la Good Will Hunting) would have done well in the philosophical discussions with Picard. The episode is interesting enough to keep you engaged the first time through, so I’ll give it a 5, but it drops to a 3 for re-watch.

Nobody’s really WRONG about flaws here, and yet I look forward to this episode every time. Rasmussen is one of my favorite Frewer characters. And though in retrospect things are written a little too conveniently, I bought the central premise that Picard and crew would not initially think of the possibility of someone from the past arriving in a ship clearly from the future.

I need to go find a book with that character in it. Maybe someone will mention it here.

tjareth: You mean the two books and one short story with Rasmussen that I mentioned right there in the rewatch entry?

—Keith R.A. DeCandido

To me, the most notable thing about this episode is how it was originally intended for Robin Williams to play the role of Rasmussen and that always be a big “what if?” for me, especially as I found Frewer’s take on the role to be annoying and unsympathetic. This was the only time I had seen Frewer act in anything aside from the Coke commercials for many years until his small part in Watchmen which I thought he was surprisingly good in, so I had always thought negatively of him because of this one episode. And this episode is one I find a big “meh” and always skip over.

@krad — It is a pity that text so often fails to convey sarcasm. It was meant as a quip on how often it came up redundantly in the comments.

One thing that bugged me early on in this episode is how everyone seems totally unconcerned (Picard included) that Rasmussen transports in a few feet away from the captain, is allowed to approach him and shake his hand…

Imagining this done with a serious looking, bearded guy who we meet pretending to be an ensign or like, a custodian, seems like could have been a really fun episode. He seems to know too much and he seems to be too curious… mid-episode, he confesses that he’s from the future, and he “proves” it by finding his vessel. But he tries to keep totally subtle and he begs everyone to go on without observing him because such historians are supposed to non-interfere!

They have to solve a problem, which he observes, but it’s not quite so dumb as the one in the episode.

In the end, he is about to leave, his handful of “confidantes” bidding him farewell, when essentially a metal detector goes off and they discover this mild fellow is comically full of stolen stuff. They run his DNA and find he was a known criminal from many years ago. He confesses that the ship isn’t his and they keep asking him questions; he is all nervous because he knows (and we don’t) that the ship is preprogrammed to vanish. (what a terrible design idea… but I guess he has it jury-rigged so … ok.)

Right when they are like “You’ll be allowed to leave when we say”, he says “Well…” and the ship vanishes, causing someone who was leaning on it to fall over.

Anyway, this version would basically solve all the problems and actually take advantage of the best part of the premise: a future guy from the past in a stolen ship. That’s gold; the rest was just dumb. I love Frewer; he is amusing in this, but they were trying for a Genie/Cat in the Hat kind of thing (maybe John de Lancie was busy) and it just doesn’t work.

P.S. Frewer was also memorably in Orchid Black, which was similar to ST: imaginative, great ensemble, great cast, fantasy/technology fun, love-based agenda, and uneven AF :)

Just me I guess but I have always found Frewer’s quirky mannerisms annoying as hell. So given that here he is playing an insufferably annoying, quirky, smarmy con-man, he should have won an Emmy.

I must say I found it curious more people didn’t pick up on the obvious piss-take of Doctor Who here. Presumably in 1991 the recently cancelled BBC show had dipped off the radar, and perhaps Star Trek’s writers thought it would never return. But seriously, Rasmussen is an eccentric time-travelling scientist with bad hair and a silly long coat.

Which, to my mind, has always made me loathe this episode, because I see it quite clearly as Trek trolling Doctor Who. Rasmussen is a fraud (just as the Doctor has no official credentials) and the Enterprise crew disable his ship and maroon him in the 24th century. Perhaps it would have worked with Robin Williams, but as pointed out, Matt Frewer is so self-consciously wacky, he’s like a bad parody Doctor. Which again, adds to the obvious sense of contempt radiating from the Trek writers.

Okay lots of commenters have pointed out the problems this episode has, but for me the biggest one is WHY does he need to travel to the future to get technology to take back to “invent”? – He already has a ship from even further in the future that contains both even more advanced technology and “future” historical data! And even if for some reason he can’t make use of stuff on the time pod and his only way to make use of it is to steel a few do-dads from another time period, why did he pick then and there? He obviously has studied up on the Enterprise before travelling to find them – but why? The time pod is capable of travelling in time and space, so why not go to some backwater colony that isn’t full of the best trained military and scientific personal of the era in question, and doesn’t have the security of one of the most powerful ships in the quadrant?

I mean, I know IRL its because it’s what the show requires, but it make absolutely no sense in any way.

On a lighter note, since this review went up we have had Holmes and Watson, so Frewer is definitely not the worst Holmes of all time now! (Though personally before that came out I would have voted for Charlton Heston for that particular honour).

I’ve always liked this one. I agree with the commentators who consider it the closest that we’re ever going to get to a crossover with Doctor Who.

@55: I suspect the first reason he couldn’t simply mine the time pod for tech is the vast gulf of foundational knowledge needed to build the time pod. To illustrate, imagine someone from the 16th century got hold of a smartphone. If they opened it up, they’d find a sandwich of glass and polymer with bits of ceramic and metal. How would they go about trying to recreate it? They’d need knowledge of electricity, quantum mechanics, miniaturization, computing, etc. Much of which they will have to invent; a task that would challenge even the greatest intellects to accomplish in a short time, much less a – as Rasmussen described himself- ‘not very successful inventor.’ Rasmussen probably strained his brain just learning how to get it to run.He likely concluded that he’d have an easier time cracking 24th Century technology after repeatedly bashing his head on 26th Century tech (not that that would have helped him much…)

In fact, I suspect he couldn’t even get the time pod out of tutorial mode, which likely limited his options on when and where he could go.

I love this episode from the moment it first aired. I love the punch-line of New Jersey especially since i grew up in New Jersey and was still living there when I watched the episode.

Yes of course there are plot issues and i have read through many of them in the comments section but it is after all a tv show and the writers have only 45 minutes or so to work with. However, one plot hole or continuity issue no one mentioned is about the century that Rasmussen states he is from. He says he is from the 22nd century (he never states what year) yet we know that WW3 (a nuclear war) happens in the mid 21st century and zefram cochrane makes his first warp flight in April 5th, 2063 which of course leads to first contact with the vulcans.

I would imagine not long after this, say a month or at the most a few months, Earth starts to change to a paradise and I would imagine a new society is also created under the guidance of the vulcans. I would safely assume the new society on earth would be an “earth unified as one with no need for currency” since the vulcans probably have replicators which can create almost anything anyone would want or need out of thin air. These events are most likely happening sometime in 2063 or at least by 2064 so by the 22nd century it would be safe to assume that people have no need for money, and that even includes people who live in New Jersey ; )

It just so happens that the 22nd century is also the century of the first warp 5 Starfleet vessel named Enterprise captained by Jonathan Archer which happens in 2163, 100 years after Cochran”s famous warp flight and first contact.

so with that being said Rasmussen wouldn’t need to “invent” new things for the sake of money. If it was glory he was after or just the satisfaction of being the one who invented some fantastic revolutionary device he could have traveled much closer to his time than going to the 24th century. If he went to 2163 he could have learned how to create a transporter and that would most certainly cement his name in the history books or padds or database. Since we don’t know what year specifically he is from he could be from late in the 22nd century after transporters were invented already. Perhaps Rasmussen should have used the time machine the other way, gone back in time with something from his time period or if he is afraid he could mess up the timeline he could pull a Back to the Future and just win a big lottery or horse race. That would of course be if it were money he was after but like i stated earlier he shouldn’t even have a need for money in the 22nd century.

Maybe I am in the minority, but I didn’t find Robin Williams to be very funny. “Mrs. Doubtfire” was his funniest performance. Other than that I never laughed at anything he did.

The British show “Are you being served?”makes me laugh harder than anything Williams did.

Here is a clip of a character making frequent allusions to her cat.

https://youtu.be/d-i523Gie9Q?si=svVwRIjXMNbG4Q6Y