As a result of a couple of recent conversations, I’ve been thinking lately about historical fantasy, and the extent to which historical norms may limit a writer’s ability to include diverse characters – whether we count diversity in terms of race, gender, orientation, or other (unspecified/name your own).

You will be unsurprised, Gentle Reader, to hear that I consider this argument (these arguments, really, since there are a number of them) a cop-out. Whether it’s deployed in the service of fantasy drawing on historical inspiration (“The Middle Ages were just like that!”), whether it’s used to support the whiteness and straightness of alt-history and steampunk, or whether it comes into play in historical fantasy where the fantastical elements are part of a secret history.

Naming no names of those who’ve disappointed me, so as not to get bogged down in discussions of niggling details, I want to talk about why the use of these arguments is a cop-out, giving historical examples. (And since I’m an Irishwoman, my historical examples will mostly be from northern Europe: I’d really appreciate if people with a wider knowledge of world history chose to chime in with a comment or two.)

A Rebuttal to the Argument That Women Didn’t Do Anything Except Get Married and Die in Childbirth (Historically):

Even if we’re only talking high politics, I see you this argument and raise you the women of the Severan dynasty in the Roman empire, Matilda of Flanders, her granddaughter the Empress Matilda, Catherine de’Medici, Marie de’Medici, Queen of France and Navarre, Maria Theresa, Holy Roman Empress, Matilda of Tuscany… I could go on. And I can’t bear to leave off mentioning the cross-dressing Hortense Mancini, niece of Cardinal Mazarin, who—after fleeing from her wealthy and abusive husband—ended up presiding over a salon of intellectuals in Restoration London.

I’m less familiar with the Great Women Of History outside Europe. But I direct your attention to Raziyya al-Din, Sultan of Delhi for four years; Chand Bibi, Regent of Bijapur and Ahmednagar; Rani Abbakka Chowta of Ullal held off the Portuguese for several decades; the Rani of Jhansi was only in her early twenties when she died fighting in the Indian Rebellion (better known to the British as the Indian Mutiny); Wu Zetian was the only woman to rule China in her own name. Need I say more?

If we’re including women who did other things? Whole industries depended upon female labour. The production of clothing, for example. Domestic service. Food production. Crime: look at the records of the Old Bailey Online. Sometimes women went to sea or to war: Mary Lacy, Hannah Snell, and Nadezhda Durova are among those for whom we have testimony in their own words, but a rule of thumb is that where there’s one literate, articulate specimen, there are a dozen or a hundred more who never left a record. They wrote socially-aware medieval poetry, natural philosophy, travelogue and theology, more theology: they established schools and organised active religious communities in the face of establishment disapproval…

They did, in short, just about everything you can think of.

A Rebuttal to the Argument In Favour Of Not Including Lesbians/Transgender/Intersex Characters:

It’s a modern invention! They might’ve been queer, but they kept quiet about it! What do you mean, cross-dressing?

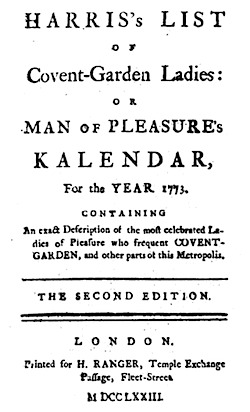

Sodomy is far better known than its counterpart. Male-on-male sexual activity has a long recorded history: in ancient Greece it was lionised as the epitome of eros, and the Classical world had quite the influence upon western European literature. The history of Sapphic love has been, perforce, rather quieter, apart from Sappho herself: for one thing it wasn’t illegal, and thus doesn’t turn up in historical court records with such frequency. But I direct your attention to Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies, an eighteenth-century directory of reasonably successful whores published yearly from the 1760s. There, among the ladies who catered for the male trade, Miss Wilson of Cavendish Square held that “a female bed-fellow can give more real joys than ever she experienced with the male part of the sex,” and Anne and Elanor Redshawe advertised their services to “Ladies in the Highest Keeping.”¹ And Miss Anne Lister, a respectable woman of the Yorkshire gentry in the first half of the 19th century, left behind her diaries, in which her amours with other women are recorded for posterity. Those with much patience are welcome to comb through the records of the Old Bailey Online for women who deceived other women, and married them while pretending to be men: there are more than you might think.

Sodomy is far better known than its counterpart. Male-on-male sexual activity has a long recorded history: in ancient Greece it was lionised as the epitome of eros, and the Classical world had quite the influence upon western European literature. The history of Sapphic love has been, perforce, rather quieter, apart from Sappho herself: for one thing it wasn’t illegal, and thus doesn’t turn up in historical court records with such frequency. But I direct your attention to Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies, an eighteenth-century directory of reasonably successful whores published yearly from the 1760s. There, among the ladies who catered for the male trade, Miss Wilson of Cavendish Square held that “a female bed-fellow can give more real joys than ever she experienced with the male part of the sex,” and Anne and Elanor Redshawe advertised their services to “Ladies in the Highest Keeping.”¹ And Miss Anne Lister, a respectable woman of the Yorkshire gentry in the first half of the 19th century, left behind her diaries, in which her amours with other women are recorded for posterity. Those with much patience are welcome to comb through the records of the Old Bailey Online for women who deceived other women, and married them while pretending to be men: there are more than you might think.

As for historical transgender or intersex persons: well, one’s recently been the subject of an interesting biography. James Miranda Barry, Victorian military surgeon, is argued convincingly by Rachel Holmes to have been a probably intersex person, female-assigned at birth, who made a conscious decision to live as a man after puberty.² (Barry was the first person to perform a Caesarian section in Africa, and one of the very first to perform such an operation where mother and child both survived.) His friends, what few he had, seem to have been perfectly aware there was something not wholly masculine about him. After his death, his doctor said he wasn’t surprised at the rumour started by the servant who did the laying-out, that Barry was a woman: the doctor himself was of the opinion Barry’s testicles had never properly dropped.

I’ve barely scratched the surface here. I’m tired of watching hackneyed treatments of women in fantasy (Madonna or whore, chaste love interest or sexually insatiable villainess) defended on grounds of historicity. There are more roles for women than are shown as a matter of course. Some of the women who filled these roles, historically, were exceptional people. Some of them were ordinary, and their actions only look extraordinary in retrospect because of our expectations about what was or wasn’t normal.

So, I suppose my cri de coeur is this: Dear disappointing authors: disappoint me less. Dear fans of disappointing authors: please find other grounds than historical verisimilitude on which to defend your favourite authors’ choices. Dear Friendly Readers: the floor is open, what are your thoughts?

¹See Rubenhold 2005, Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies; Cruickshank 2010, The Secret History of Georgian London; Arnold 2010, City of Sin.

²Holmes, 2007, The Secret Life of Dr. James Barry.

Liz Bourke prefers being pleasantly surprised to being disappointed. Alas! The latter happens far too often. Find her @hawkwing_lb on Twitter, where she complains about quotidiana and catalogues her #bookshop_accidents.

Good piece. I would draw your attention to the Aubrey/Maturin novels by Patrick O’Brian which, despite being set primarily in the Royal Navy of the early 19th century, have a significant number of strong female characters.

Thank you for this.

Just last night watching Moonrise Kingdom (which I loved overall, by the way), I noticed something that irked me. After a huge group of boys decide to break the rules, endangering themselves and others, the question one of the leaders asks is, “Who is this bimbo?” I remarked on it to my husband, and he said, “It’s 1965.” To which I replied, “It was written a couple years ago.”

The mindset you write about is incredibly pervasive. “Well, it was a different time.” “Well, women didn’t have power back then.” “Well, black people were slaves.” That doesn’t mean powerful people vanished outside the white male majority — it just means they got less air time.

Brilliant article. Definitely shared it.

For early history of the US and the freeing of slaves, for those who say that it just couldn’t be done, I’ll point to Robert Carter, who freed all of his slaves (over 500), by choice, without compensation, because he grew to believe it was the right thing to do.

He also did not force them to leave the area. This was something that other would-be emancipators such as Jefferson considered a necessary component to emancipation, and something that made emancipation far more complicated than it needed to be. It also created a false labor crisis when slaves were freed – who would do the work that they had been doing?

Rather, Carter arranged his emancipation plan so former slaves could leave if they wanted, or they could rent farms from him. He’d also developed various industries beyond agriculture on his plantation, so many slaves were skilled workers, such as blacksmiths, and they had that skill at their disposal once free. This led to the growth of large mixed-race communities that included a substantial free black population. His answer to who would do the work that slaves had done, if slaves were free, was that the people who had been enslaved were already skilled at that work, and could do it for their own profit or for pay.

Carter’s family was not as rich when he was done, at least on paper, as they were before. But they weren’t poor. They had land, worked by free tenants. They had industries, employing skilled workers. They had servants, paid with the money they made through leases and the industries they ran. And they lived in a community that was safer and better than what they started with.

Likewise, while the family had debts before the emancipation, and after, he didn’t use debt as an excuse not to free his slaves or to sell them to pay off debts. Instead, his business was restructured to be profitable when done with paid free workers rather than slaves, and paying money debts was put in second place to paying the debt of freedom he owed to people he’d enslaved and exploited.

Just as the examples above make a lie of the claim that women didn’t do anything or that QUILTBAG folks didn’t exist, this puts lie to the claim that freeing slaves was too complicated, expensive or impractical.

Carter lived in the same area of Virgina as Washington and Jefferson. They knew about his emancipation work. They knew that it was working out in a practical manner – and they also saw the loss of social and political power that Carter experienced when he was osteracized by other slaveowners of his class and community. And despite pretty words saying they wanted to free their slaves, neither Washington nor Jefferson followed Carter’s example, of either embracing emancipation nor accepting the personal changes that came with defying social expectations.

http://books.google.com/books/about/The_First_Emancipator.html?id=qmHZ_MKXN5EC

I found out about this book a little while ago, via the excellent blog Slactivist. http://www.patheos.com/blogs/slacktivist/

Speaking of the Aubrey-Maturin books, I feel like I should point out Jo Walton’s excellent Patrick O’Brian re-read, in case anyone’s interested…

@emmie Mears: I also loved Moonrise Kingdom (I was surprised by how much I enjoyed it), but for what it’s worth, I’ve had a couple of conversations about that line, and I think Harvey Keitel is actually calling Edward Norton’s character a bimbo, in keeping with Wes Anderson’s idiosyncratic, whimsical use of language and slang here and in his other films. “Bimbo” actually started out as a slang term for “an unintelligent or brutish male,” and the term pops up in relation to men throughout the 1920s (especially if you read a lot of hardboiled detective fiction, which is where I first encountered it).

I know the film is set in 1965, but Keitel’s character is an old-school, blustery sort of guy, and the conversation itself, ending with “And now he’s lost his whole troop? Who is that bimbo?” (emphasis mine) centers on Norton, not on Suzy (or any other female character). I think if you watch it again, it might make more sense (and come off as more amusing than offensive, if you agree that the insult was aimed at an adult, male scout leader :)

Agreed. Anyone who uses the “historicity” argument is just being lazy. We tend to see books written about, or inspired by, the extraordinary people in history, which is ok if they are men, but ignored if female. I think it is alright to use historical settings, even when they include oppression, but for Pete’s sake, stop using that as an excuse to not write compelling characters.

@BMcGovern- Thanks for that write-up on Moonrise Kingdom. I was having trouble remembering the “bimbo” reference, especially since it seemed out of character for Anderson in the context given by @emmie Mears. In a summer of cinematical disappointments, that movie was a breath of fresh air. Along with Beasts of the Southern Wild…which come to think of it, applies to this post (and Sleeps With Monsters as a whole).

Counter-request: when you DO write female / LGBT / POC characters into your alt-history, please don’t write them as if they were modern socially-aware activists. Let them have era-appropriate thinking, even if they are rebeling against an establishment that disenfranchises them. Case in point: Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn helps a fleeing slave, but the society he lives in has indoctrinated him that slavekeeping is good and what he’s doing is tantamount to theft of property. He therefore reaches the (obviously incorrect) conclusion that he’s bad to the bone and cannot and will never reform. The reader of course knows better – Twain gently lets the reader draw the correct conclusion without having his protagonist proclaim it in speech or even be able to formulate the though himself.

@Ursula: Thank you for letting me know about Robert Carter. I have been busy learning about him for the past half hour now, and I am very glad to have had my attention drawn to him. He, moreso than the “founding fathers”, is worth remembering from that time.

@Michael_GR: That said, it’s easy to fall into the opposite trap: “Everyone in this time period must have believed exactly the same things about all of these issues, and it’s anachronistic for anyone to believe otherwise.” Mark Twain was, after all, gently allowing the reader to draw a different conclusion than his protagonist while writing about a time period he wasn’t exactly all that removed from himself.

I’ve occasionally seen books criticized for having protagonists with “modern thinking” when said protagonists are saying and thinking things which people of that time period did say and think; it just wasn’t the dominant viewpoint. (Or sometimes it just wasn’t the viewpoint that people these days think was dominant.) There were abolitionists well before the Civil War, and atheists in ancient Rome.

I do agree that it gets weird if all the Good People in a story think exactly the same as modern (insert author’s preferred political group here) with the exact same language and so forth. But it’s equally a mistake to think that everyone in non-modern times had lockstep offensive views on all issues.

I’ve been watching a lot of Korean dramas lately, and I’ve noticed that showing historical women in positions of power and influence is something they do particularly well. Queen Seon Duk is a great example; her father had three daughters and no sons, and so selected Seon Duk as his heir. (Wikipedia says “The act was not unusual within Silla, as women of the period had already had a certain degree of influence as advisors, dowager queens, and regents.”)

The Princess’s Man and the currently airing Faith also do a fantastic job of showing historical (and fictional) women in positions of power and influence–and, even when restricted by society’s conventions, acting within their sphere to exert whatever power they could. The Princess’s Man is especially good at this. It has some great conversations about women’s roles and influence, and ladies who are awesomely badass without ever picking up a sword.

Oh yes. There are a lot of things around undervaluing women’s contributions to society that frustrate me, but even when you put women in the domestic sphere the lack of appreciation of how difficult running a household successfully was, the difference it would make to the health and wellbeing of it’s members really irritates me. For most of our history even the richest households could not just buy their way out of bad times, because in many areas there wouldn’t have been anything to buy and even when distance markets had developed they would not always ahve everything needed on tap the way a supermarket does. A good household manager could make the difference between lif and death for it’s members, yet it’s ‘just women’s work’. I could rant on this for some time, but I’ll leave it there.

Albert Cashier, a veteran of the Civil War, medal and pension recipient and married man, was struck by a car and brought to the hospital in the early 1900s, where it was discovered that he was a woman. There are believed to have been approximately 500 women at least in the armies of the Civil War, some of whom were caught (one after she gave birth in the tent she shared with her husband!), some of whom were not. One of the dead in front of the stone wall at Gettysburg was a woman.

Let’s not forget Joan of Arc, Catherine the Great, Pope Joan, Molly Pitcher, Sybil Luddington, Elizabeth I, and the Pharoah Hatshepsut.

I very much agree. It seems that too many writers have a very limited knowledge of history, too influenced by the Victorian views. Also for some reason find they find it perfectly acceptable to introduce things like dragons, magic, etc, and other non-historical elements, but creating a society which is not completely patriarchal and where women have other roles besides mothers and prostitutes is unthinkable, which I find really illogical.

Case in point: Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn helps a fleeing slave, but the society he lives in has indoctrinated him that slavekeeping is good and what he’s doing is tantamount to theft of property. He therefore reaches the (obviously incorrect) conclusion that he’s bad to the bone and cannot and will never reform. The reader of course knows better – Twain gently lets the reader draw the correct conclusion without having his protagonist proclaim it in speech or even be able to formulate the though himself.

Twain goes much farther than that. There is nothing gentle about what he is doing.

Hucklberry Finn grew up in and lived in a community where helping a slave escape was one of the worst possible crimes and sins. Something that promised punishment in this world and the next.

And Finn does not merely do what is right, anyways.

He does what is right while still completely believing that doing so will lead both to severe punishment in this world on the chance that he is caught and that it will lead to certain, eternal, and torturous punishment in the next life.

“I’ll go to Hell.”

This is a challenge to the reader. What harm will we accept, what punishment will we anticipate, and still do what is kind and good to other humans anyways? Will we pay fines? How high of a fine? Will we go to prison? Will we see our children go into foster care because we are in prison and cannot care for them? Will we loose our homes and property? Will we face a prison that is not just prison, but a badly run, anarchic and abusive prison, where we can expect starvation, beatings and rape? Will we do what is right even if it costs us our lives?

Will we do what is right and kind and good even if it costs us not only our lives, the safety of our children, ownership of all our money and property not only for our own use but for the use of our families and heirs, our physical comfort and safety for what is left of our lives, and eternal torture after that?

The people making laws to support and protect the institution of slavery were deadly serious about what they were doing. They knew they could not make a strong appeal to creating and enforcing laws that were just. So they went for creating laws that carried punishments so severe that almost everyone would find the prospect of the punishment to outweigh the moral call of doing what was right.

Because that is what Huckleberry Finn knows that helping Jim might cost him. And he helps, anyways.

And yet Twain holds back from illuminating the full possible cost of Huck’s choice. Fines? Huck has no money, and would never be able to pay a fine. Family? Huck has no family, so the way that the punishment for his actions affects him does not mean that he’s worried about hurting anyone other than himself, let alone the worry of hurting anyone he loves as close family. Salvation? Huck has led an odd enough life so far, so that he’s not counting on salvation. There is an element of “I’m damned anyways, so I might as well be damned for this as well.”

A very different choice from what an adult, married homeowner and business owner with minor children would face when an escaping slave needed help. Huck’s choices can harm no one but himself.

@Bergmaniac

That is one of the things that I really enjoy about The Wheel of Time. Robert Jordan built a magical matriarchal society, and it’s pretty consistent. It also informed the world at large and the positions that women hold throughout the world.

@Liz

You might be interested in reading about some of the tribes in the Americas. Many such had women in leadership roles, and while there were gender assigned roles, they were not always the same as you might find in European societies. Cherokee women for instance freely participated in government and where the homeowners.

I’ve always wondered about the Spartan Women. Contemporary historians at the time only commented that they showed too much thigh. But as the free men were together most the time in the barracks and the mess, I’d have to assume the free Women were together in a similar way eating together and teaching each other.

The West was build on Judeo-Christain principles and was the zenith of world civilisations. Twas build on God, guns and a search for glory and angst liberal retrospectives to read in diversity where none really existing in the ruling classes at the time (edge cases like Peter the Great’s Gannibal included) is pure fantasy.

Patrick M. @17 is such a perfect example of wrongness that one is tempted to believe they’re having us on.

It’s heading on for midnight where I am: I hope tomorrow I can come back and join in conversation with the comments here with the attention they deserve. (Not ignoring the wonderful interesting conversation today! Just too swamped to participate properly.)

Jazzlet @10:

Yes. The management of a household was vital work. Particularly for families who didn’t reside in large towns.

Tamora Pierce @11:

That’s really cool. Is there a book or anything about Albert Cashier and their female comrades?

SkylarkThibedeau @16:

*is classical historian* *can share reading list*

We don’t know nearly as much about Sparta as we’d like to – or as we think, since most of what’s written about the Classical Spartan way of life comes from centuries later with the likes of Plutarch. It seems the women of Sparta had greater scope for activity than in many other Greek poleis, but not enough information survives to allow us to be certain of the limits of that scope.

If you’re interested, I can recommend Sarah B. Pomeroy’s Spartan Women as an introduction.

Ah, crap. I was about to congratulate the readership of tor.com on finally having a Sleeps With Monsters column without comments about how prejudice is awesome and justified and trying to stamp down on it is just denying the truth. And then along comes post 17.

At least the haters are starting to sound like a lone voice ranting in the wilderness, and not a chorus.

As for Patrick M. @17:

First, define “West.” Next, define “Judeo-Christain.” Further, provide examples to support your claim that it “was the zenith of world civilisations.” On what grounds do you claim the accolade “zenith,” and for what portion of the vast and yes, historically diverse set of nations?

Further to this, define both “God” and “glory.”

Further to this, demonstrate a) an understanding of the influence of Muslim intellectuals on the European Renaissance; b) the extent of learning, prosperity, and international exchange within the Dar al-Islam up to the 18th century; c) the nature and variety of cultures within any two of the following: i)the Americas, ii)sub-Saharan Africa, iii)the Pacific islands, iv)Central Asia, v)East Asia, vi)Southeast Asia, vii)India, viii)East Africa, from any historical period prior to your lifetime.

For bonus points, outline the existence of either a)the black African or b)the Sephardic Jewish communities in eitherTudor England or Early Modern Amsterdam, and describe the composition and relationship of the Holy Roman and Ottoman empires in the Early Modern period.

…Or maybe you be trolling, man. In which case, go bother someone else.

Interesting article. The comments have definitely moved on from when I left to check out a few of my old university texts for names of interesting Medieval women (Medieval studies was my major but I haven’t kept up with my studies as much as I’d have liked since school). Anyway…

If people want to know more about what women were like in the Middle Ages, there are several books on the subject. For a quick overview with some case studies, there’s Women in the Middle Ages by Joseph and Frances Gies (it’s an older title). For newer works, there’s Women in Early Medieval Europe 400-1100 by Lisa Bitel. A personal favourite – with lots of interesting women – is Vicki Leon’s Uppity Women of Medieval Times. She’s done books for sevearl historical periods.

There are any number of women of interest, especially where the church was concerned: Hildegard von Bingen, for example, was an abess and wrote about her visions, medicinal herbs, wrote sheet music and more. Clare of Assisi founded the Poor Clares, Christina of Markyate was married off but wanted to join a nunnery and therefore refused to consumate her marriage until her family gave in and let her go. Margery Kempe wrote about her life (as wife, mother, pilgrim and mystic). St Balthid, wife of Clovis II rose from an Anglo-Saxon slave to become the Frankisk Queen (though the source for this is her saint’s life, which are generally sketchy when it comes to facts). Still, in the saint department are: Perpetua, Catherine (of the Catherine’s wheel), Margaret (and the dragon), Agnes, etc. These are all women who either left records themselves (being higher class/religious they tended to have more education) or were written about by men (usually as saint’s lives or hagiography).

For non-religious writings there’s Marie de France’s Lais, which tell some early Arthurian legends and the characters in popular writings by men: think Chaucer’s wife of Bath or the wife from the Miller’s Tale.

The information is there if authors – or readers – care to find it.

I can’t believe that in this discussion of powerful women in medieval times that no one has yet mentioned Eleanor of Aquitaine, queen consort of France, later queen consort of England, who ruled as Regent while her son Richard (yes, that Richard) was off traipsing around the Holy Land crusading. Rich, powerful, and absolutely fascinating to read about. The history books don’t do justice to so many fascinating people from days gone by, and certainly women are generally under-represented. But that doesn’t mean they didn’t have a major role, just that it was not well recorded. History books fail by focusing too much on war and politics, and not enough on other aspects of the human condition.

hawkwing-lb @21: You are my new hero.

Anyway, talking about historical women… One of the things I love about real actual history (as opposed to the cursory impressions of it that most of us get via high school) is how women did, in fact, get to be bad-ass in all sorts of ways. Warrior women? Sure. Disguised as men, and not! Scientists? Ayup, and ditto. Leaders? See previous. Negotiators, manipulators, and powers behind the throne? Ayup. Unrecorded heroism going on in places the people writing down the histories didn’t notice? Also there!

Because it’s nice that we’ve got the dramatic war hero types, but there were also all those women out there being powerful and proactive and the heroes of their own stories in the roles that men didn’t even notice. Which is awesome in its own way. One of my favorite parts of Bujold’s A Civil Campaign is when a lady of society gears up with other “useless” noblewomen to make a major political move… in a way that a lot of the men around them will never even realize, because they’re not actually going out and doing something unusual for their class, status, and gender. They’re doing something that they’ve been doing all along, and which has escaped the notice of the men who think they’re controlling everything.

I mean. Not to wander into the whole unfortunate implications of Women As Manipulators, but I like that that’s an option, too. Even in highly segregated and unequal societies, women have ways of pursuing and affecting things within the restrictions of their cultures, as well as without.

“Even in highly segregated and unequal societies, women have ways of

pursuing and affecting things within the restrictions of their cultures,

as well as without.”

Indeed.

One of the most fascinating bits of history I read while I was in college was a paper about a prostitutes strike in Hawaii during the second world war. It was one of those times where the mere idea of it blew me away – and yet the more I thought about it the more I realized how much sense it made.

Somehow history and womanly-ness both get framed in such a way as to seem polar opposites, even when one is talking about women in history. History is the flashy stuff that gets written down; the wars and politics, as AlanBrown pointed out. (And only specific aspects of war, at that.) Women are merely the helpless creatures that existed within that framework.

Stories like that of the striking sex workers shatter those false ideas about women and history because they show how, even when confined within certain gendered roles, women were never actually constantly passive the way it is often asserted they must have been.

It’s one of the stories I tend to think about when the argument that “Women Didn’t Do Anything Except Get Married and Die in Childbirth (Historically):” is made. Because even if all women everywhere in the past had been confined to marriage, children, and/or prostitution, to act as if that that encompassed all of who they were or how they impacted society as a whole – that’s a tremendous lie all by itself.

Women pirates are a great example of women acting outside the traditional female sphere but you are absolutely right that women who were INSIDE that sphere were just as active contributors to society.

Rome is my area of expertise and the women of Ancient Rome were fascinating, even though they were specifically excluded from public politics and the military. Instead they involved themselves in the private side of politics, religion, craft, the family, socialising, and all manner of activities.

We also have a whole lot of poetry and other sources about m/m relationships, and the complex relationship that Romans had to sex – they certainly didn’t believe in the idea that people had just one sexual orientation, being far more concerned about the class issues involved in any pairing.

Those interested in historical people who don’t conform to the gender binary should also look up Catalina de Erauso, who was raised to be a nun but ran away from the convent, dressed as a man, joined the military, and went to South America — where she reportedly served with her own brother without being recognized. She later got a dispensation from the Pope to wear men’s clothing.

Loving this conversation!!

Wanted to add, as someone else mentioned, most of the supposedly historical roles depicted in conventional fantasy are largely Victorian roles tricked out in medieval dress, so they fail the test of historicity before they even get out of the gate. About as historical as those 50’s costume dramas where everyone is wearing historically accurate dress with 50’s hair and makeup.

I first came across this aspect of history in the early issues of the British magazine Miniature Wargames, where there were several articles about the historical women of military and political significance. This would be 1983 and ’84.

And locally we have Lucy of Lincoln, who gets a more confused write-up on Wikipedia than she does at Lincoln Castle.

One of the odd assertions I recall from those days was the the Victorian historians were less inclined to hide such people than their successors were. Now it’s easy to see the two World Wars, with their mobilisation of women while the men went off to fight, and then the backlash when the men came back, as encouraging a cover-up.

And I’d also commend the historical novels of Lindsey Davis whose novel “Course of Honor” about the historical Antonia Caenis paints a portrait of this powerful woman which exemplifies the characteristics Ms Bourke describes as well as Davis’ fictional character, Helena Justina in her wonderful Falco series of novels. Her upcoming new fictional series of novels, again set in Imperial Rome, will feature a female lead, and I can’t wait to see what she does with it.

Like Ms. Bourke, I feel strongly that genuinely powerful women are anything but an anomaly in historical terms. Just because that power was expressed differently that it can be in modern terms doesn’t mean for a minute that it wasn’t present and very, very real!

Ancient Greeks didn’t conceptualize sexuality or sexual identity the way we do. “Straight” and “gay” are meaningless in that context. They thought more in terms of… hmmm… “pitcher” and “catcher” would be the closest modern analogues.

Women were catchers; males could be either pitchers or catchers. It was intensely sexist and patriarchal, but not in the way we’re accustomed to outside jail. Which Classical Greek life resembled, in some respects.

This illustrates the way that while biology is a constant — human nature has no history — how it’s thought about varies extremely widely. And since human beings are intensely cultural, that matters a lot.

The real “sin against the literary Holy Ghost” is imposing contemporary sensibilities on times and places where they just… don’t… fit.

It’s easy to see someone else’s cultural biases; hard to see your own, like water to a fish. They feel intensely “natural”, but they ain’t. Expose yourself to the shock of Otherness; don’t insist on the familiar, on what feels right and good.

As the above example shows. This certainly applies to historical fiction, and IMHO should also apply to fantasy and SF where the cultural setting is very different from ours.

Also, remember that exceptions are, like, -exceptions-.

Frex, there were always women who assumed “male” roles. This happened, although it was nearly always frowned on and often illegal/heavily punished.

It was also -rare-. One of the reasons it was even possible for women to masquerade as men was that gender distinctions in dress were so strong that the eye didn’t ‘see’ what would be to us fairly obvious physical clues. It’s actually harder for a woman to successfully pass herself off as a man now than it was 150 years ago, though not impossible.

You weren’t going to come across dashing cross-dressing swordswomen around every corner in 1600, in other words. Did they exist? Yes, and people told stories about them. Was it likely that any given individual would ever actually meet one?

Hell, no.

Most women spent a -lot- of time being pregnant and nursing infants. Most of the rest of what they did in most times and places (and of course most people of both sexes worked hard at subsistence tasks all their lives) was intensely gendered, and ordinary people could no more escape this than they could float gently upward by sheer willpower.

And the fact that some men lived in terror of their wives (a real phenomenon, as anyone who’s read Chaucer knows) didn’t alter the fact that society was male-dominated.

Nor did the fact that women were often -influential-; eg., the way noblewomen often threw heavy political heft. Influence is not the same as power.

Her courtiers and ministers sweated with fear when Elizabeth I got angry; that didn’t make Elizabethan England a matriarchy. She wouldn’t have been Queen (or lived through Bloody Mary’s reign) if she hadn’t been a very smart political operator and a very tough cookie… but if she’d had a surviving brother, she wouldn’t have been Queen, period.

As Marx observed, human beings make history… but they don’t make it ‘just as they please’.

You’re always historically located and that determines the possibilities of your life. In the context of gender relations, don’t assume that a feminist revolution was always bubbling under the surface, ready to break out.

It took a very specific confluence of historical factors, technological, political, religious, intellectual, to even make it possible to -think- that way.

-What- was regarded as specifically female or male varied widely; frex, as “spinster” suggests, spinning thread was women’s work in Western civ. Weaving, on the other hand, was usually done by men.

If you read about the plight of handloom weavers in early Victorian England, where power looms were throwing them out of work, note that they were pretty well all men. There was no inherent reason for this even by the standards of the time and place — it was work done at home, could be interrupted at will, and needed mostly manual dexterity and patience. (Which qualities were basic to virtually everything that -was- classified as women’s work.)

It was just male by “nomos” — local custom. Probably because, before the power loom, it was quite well paid as working-class jobs went.

Most of the time most people just accept the moral and ideological context of the culture and sub-culture(s) they’re born into the way a fish does water.

People -game- the system incessantly; sometimes they’ll blithely assume that the rules don’t apply to -them- however good they are for others, but actual root-and-branch dissent is fairly rare. Particularly before the Enlightenment. It wasn’t intellectually “available”. Anti-clericalism and contempt for priests was common as dirt in the medieval period, for example, but you could probably have gotten all the actual atheists in 12th-century Europe into one medium-sized church.

Don’t assume that people couldn’t “really have believed that”. Or that only -bad- people could “really have believed that-. Yeah, they did, and no, they weren’t ‘bad’, they were just different from us. Lived in different perceptual universes, had different moral systems.

Exemplia gratia: THE CAVALRY MAIDEN, which is the largely true memoires of a Russian noblewoman who enlisted (disguised as a man) in the Russian cavalry during the Napoleonic Wars. She leaves stuff out — she doesn’t mention that she was married and had a son before she ran off to join the army– but doesn’t outright falsify.

If you read the (very interesting) autobiography, you’ll note that she has no doubt about the essentialist beliefs about masculinity and feminity of her culture; she just doesn’t believe they apply to -her- . Logical consistency is not something non-intellectuals care much about.

She also believes fervently in Holy Russia, in the benificent autocracy of the Czar, and casually despises Jews. In other words she’s a fairly typical member of her time and service-nobility class… with, of ourse, one exception.

Exemplia gratia two, illustrative of things about both in the character and the author, and from just before I was born: EARTH ABIDES by G. Stewart, classic post-apocalyptic SF story written in the late 1940’s.

The hero finally meets up with a woman in the plague-swept wasteland. They hook up, she gets pregnant. At this point it’s revealed that she isn’t white — specifically, she’s (a very small) part black on her mother’s side, and decides to tell him in case he wants to back out.

At this point something goes “bing!” in the hero’s head. A lot of stuff about Em is -explained-. Her passive, accepting nature for example…

Ish, the hero, is a good guy. There’s not the slightest suggestion that he even considers regretting his decision to marry Em. By the standards of 1949 (when miscegenation was -illegal- in much of the US and social death in most of it) he’s a flaming liberal (as I suspect Stewart was).

But the above thought is absolutely natural to him. I suspect that a lot of authors today wouldn’t -dare- to show someone from that period thinking like that unless he was a cackling villain — which shows a failure of nerve.

The past is another country. They do things differently there.

Queen Nzingha a Mbande, who held off the Portuguese slave traders in her land, called by them Angola, because the Portuguese mistook her title for the name of the land.

Love, C.

S.M. Stirling: But the above thought is absolutely natural to him. I suspect that a lot of authors today wouldn’t -dare- to show someone from that period thinking like that unless he was a cackling villain — which shows a failure of nerve.

Do…do you read things that people write and which are published these days? At all? Do you watch modern television, especially historical shows? Have you ever read A Game of Thrones or seen the HBO series Rome?

Because I really cannot take anything you’re saying seriously if you are earnestly claiming that paragraph above to be true. Fiction written by modern authors is RAMPANT with people writing protagonists and heroes–in characters intended to be sympathetic to the audience–who hold views that are utterly antithetical to their modern audience. Far, far more so than the views about “miscegenation” which polls show a fair number of people still hold today.

I’d also recommend doing some more research on how “Ancient Greeks” thought about sexuality, rather than parroting a rather limited and antiquated view of that culture based on a pretty limited sample set. Courtesans & Fishcakes is a great book for that purpose; it talks quite a lot about the powers and positions that women had in Athens, even within the rather narrow range of women selling sex to men.

Frankly, your entire comment is so full of assumptions based on lack of research that I’m not sure it’s worth addressing the rest of it directly.

Thank you all, even Patrick M., whom I suspect was being ironical.

The list of women who deserve a place in our history books – and not just in “Womens’ Studies” courses – could occupy volumes.

It’s interesting that nobody’s yet mentioned the Byzantine empresses, many of whom were not only world shakers, but also exploited the norms of their time – when the threat became too pressing, they would retreat into a nunnery, but they were always ready to sally forth and trounce their opponents.

And, of course women were not only rulers and warriors, but artists and writers, scientists and mystics – and, as Jazzelet points out, ordinary women who kept the whole society afloat

And there had been people of colour in the UK at least since Roman times, while LGBTs and “the disabled” have been around as long as ‘homo’ has been ‘sapiens.’

I write pseudo-historical epic fantasy and out of my own experience I can tell you that some readers balk at the idea of gay characters in even a pseudo-medieval setting.

Magic and talking dragons (of which my novels have none — just the one heraldic dragon) seem to be no problem for their suspension of disbelief. A gay warrior-prince who wins battles on the other hand…

@35, They never heard of He Man have they?

All valid points. Keep in mind that Celtic literature is filled with strong female characters, both politically powerful and warrior women. Norse literature frequently mentions shieldmaidens.

Urraca of Castile-Leon’s divorce from her husband, Alfonso the Battler of Aragon, and conflict with her younger bastard half-sister Theresa had a direct impact on how the Iberian Peninsula looks today (Theresa, Countess of Portugal, was instrumental in breaking away from Castile-Leon). It’s said she lost every military battle against her ex-husband (who was deemed by many the greatest warrior of his age), but won everything back and more to her own much-larger kingdom through superior diplomacy. Plus, both she and Theresa openly cougared their way through their noble retainers in a manner that would have made Catherine the Great blush.

The female members of Alexander the Great’s family were downright terrifying.

Ermengarda, local noble ruler of Rourell (in Catalonia) following her husband’s death, was the Preceptrix of a Templar house who accepted brethren to the Order–her assistant a woman named Titborga.

Theodora rose from low-born actress (and probable prostitute) to Empress of the Byzantine Empire.

Many of the early leaders and martyrs of the Christian Church were women.

Ching Shih is believed by many to be the most successful pirate ruler in history.

Tomoe Gozen was a mighty samurai warrior, general and vassal.

Women in Medieval Europe, and Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, were responsible for most of the beer-making (and selling) in their cultures. Like your malt? Thank women.

One really annoying thing is that the accomplishments of some great female rulers are co-opted by their male successors, even though said men wouldn’t have been successful at all on their own. This applies to rulers like Hapshepsut, Matilda of England, and Theresa of Portugal.

Another woman in history I love is Agnodice.

Basically, she saw a bunch of women dying of childbirth and really wanted to help, so she left Athens and went to Egypt where, unlike in Athens, women studying medicine wasn’t punishable by death.

She eventually went back to Athens as a man to help women deliver children, occasionally revealing herself as a woman in order to gain trust, and eventually many women knew her secret and sought her help over the men.

The male physicians got really pissed off that women no longer wanted to be treated by them, and they accused Agnodice of seducing female patients. When she went to trial in front of the physicians and the patient’s husbands, she refuted the claims by proving she was a woman. They then accused her of deceit and wanted to kill her, but all the women she saved came and chastised their husbands, since she was basically the reason they had wives and children.

Hence the law was changed to allow women to practice medicine in Athens :)