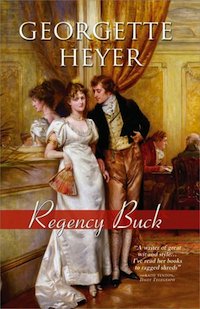

After publishing eighteen books, ten of them historical, Georgette Heyer finally turned to the period that she would make her own: the Regency, in a book titled, appropriately enough, Regency Buck.

And oh, it’s awful.

Well, maybe not awful. Let us just say not very good.

The wealthy Judith Taverner and her brother Peregrine (his name is but the start of the problems) have decided to leave the north of England for the delights of London. On their way down, they quite by chance meet their cousin Bernard Taverner, a charming if somewhat (by the standards of the British aristocracy) impoverished young gentlemen; several assorted Historical Figures whose names are but the beginning of the many, many, proofs we will have that Heyer has Done Her Research; and a rather less charming young gentleman who sexually assaults Judith Tavener, kissing her against her will and insulting her.

Naturally, by the time they reach London, they find out that the rather less charming young gentleman is in fact their guardian, the (dare I say it) Proud Earl of Worth. Naturally, thanks to the entire assault business, Judith is Prejudiced against him, instead falling, or almost falling, for the charms of Bernard Taverner, even if the Proud Earl of Worth is, to quote Charlotte Lucas, ten times his consequence.

If you are getting uncomfortable reminders here of Pride and Prejudice, well, that’s hardly a coincidence: Regency Buck uses, for all intents and purposes, the same plot, right down to featuring a near elopement in Brighton. The language is deliberately chosen to echo that of Austen’s novel. Judith even uses some of Elizabeth’s phrases in her inner monologues. But Judith Taverner, unfortunately, is no Elizabeth Bennet. She lacks the wit and charm and above all, intelligence of her predecessor, as well as Elizabeth Bennet’s grip on reality. For that matter, Judith Taverner is probably less intelligent and aware than the silly Lydia Bennet, and is the only fictional character I can think of who would be improved by a conversation with Miss Mary Bennet.

Beyond this, she lacks one major feature that immediately makes Elizabeth sympathetic: Judith, unlike Elizabeth, is rich. Very rich indeed. If Elizabeth does not marry, she faces a lifetime of seeking charity from relatives at best; if Judith does not marry, she can buy a mansion and a few extra horses, or head off to Europe with a nice paid companion and plenty of servants. I am leaving out more useful things that Judith could be doing since Judith does not seem to be that sort of person. Judith can, bluntly, afford to quarrel with wealthy people (well, most wealthy people; she doesn’t defy the Regent.) The worst Judith faces is ostracism from London society, and given her money, even that proves easy to avoid.

The money also, naturally, makes things much easier for her all around. She is immediately accepted into society and has several offers of marriage (she finds this depressing because they are mostly fortune hunters). She even attracts the serious attention of a Royal Duke. When she decides to head to Brighton, money and transportation are no trouble. And no one, readers or characters, questions that she is an entirely suitable match in fortune and rank for the Earl of Worth, again in direct contrast to Elizabeth.

Since she has so many fewer obstacles than Elizabeth Bennet, Heyer is forced to up the consequences by making the villain so much, much worse, changing his crime from seduction of teenage girls (and, well, gambling and spending too much money) to attempted murder and kidnapping. Heyer almost manages a creditable job of hiding the villain until the very end (it would work better if she were not at so much pains to quote phrases from Pride and Prejudice, giving Bernard’s role away in the first quarter of the book), but about the only real justification Judith has for not realizing the truth earlier is that, let’s face it, Bernard’s motives for said attempted murder and kidnapping are weak indeed. His motivation is, supposedly, money, and while that’s a fairly standard motive for fictional murders, here it doesn’t work, since Bernard is simply not that poor—and has every expectation of marrying a wealthy woman. Like, say, Judith, but even if that flops, Bernard has the family and social connections to marry well. He is evil only because the plot needs him to be—and because without the revelation of his crimes, Judith would have every reason to marry Bernard, not her Destined Romantic Partner, the Earl of Worth.

After all, the Earl of Worth, whatever his pride, is, to put it mildly, no Mr. Darcy.

Oh, he is rich, certainly, and proud. But where Mr. Darcy starts his book merely by insulting Elizabeth (and then has to spend the rest of that book making up for that lapse), the Earl of Worth starts his book by insulting Judith and forcing a kiss on her—after she has made it plain that she wants nothing to do with him. Heyer details Judith’s shock at this: Judith is prudish in general, and particularly prudish about merely touching strange men, let alone kissing them. Her brother is justifiably outraged. Things don’t improve. Worth humiliates and threatens her. They have several violent quarrels. Frankly, by the end, I was thinking kindly thoughts of Mr. Wickham. And yet I’m expected to believe Judith and Worth have fallen in love.

Well, okay, yes, he does save her brother. But. Still.

Why do I find this so much more irritating here than in Devil’s Cub, where the romance began with an attempted rape? Because although Vidal is considerably worse by all standards at the beginning, Vidal also offers hope that he might change. A little. And because Vidal is responding to a trick Mary played on him and has some reason to be annoyed and believe that Mary’s morals are pretty loose. Judith, when picked up against her will, forced into a carriage, and kissed, is on the road with a broken shoe. Vidal almost immediately recognizes his mistake and attempts to rectify matters, and when Vidal says he realizes he cannot live without Mary, who is the first person to be able to change him, I believe it.

Worth never changes; he takes a long time to recognize any mistake, and when he says he cannot live without Judith, I don’t believe it. It doesn’t help that although they are social and financial equals, they are not equals in intelligence; I have to assume that after a few years Worth would be desperately wishing that he had married someone considerably brighter. Judith manages to misinterpret and misjudge virtually everyone in the novel, right down to the Prince Regent, which in turn gets her into avoidable situation after avoidable situation, irritating or distressing nearly everyone, right down to the Prince Regent.

Not that Worth is much better, although at least he’s a better judge of people. But his rudeness, a character trait that Heyer had turned into high comedy in previous novels, is here simply irritating, especially since we are told that Worth isn’t always rude to everyone. Just Judith. I suppose we’re meant to believe that Judith rubs him the wrong way, or that his attraction to her sets him off balance, but instead, he comes across as emotionally abusive AND rude and arrogant. Heyer later recognized her mistake here: her later arrogant and rude heroes would have these traits used for high comedy or punctured by the heroine. Worth’s emotional manipulations of Judith are not funny, and although Judith quarrels with him, she never punctures that rudeness, making their conversations painful instead of funny. Indeed, humorous moments are few and far between and mostly focused on the Duke of Clarence, a minor character.

The failed romance and the borrowings from Pride and Prejudice are, alas, not the only problems with this novel, which suffers from two other problems: one, it is frequently dull, partly because two, it contains far, far, far, far far too much dropping of historical facts. If a major aristocratic personage of London during the Regency period goes unmentioned here I missed it. We have the careful name dropping of various Royal Dukes; various non Royal Dukes; various writers and poets (with Jane Austen carefully referred to as “A Lady,” as she would have been known at the time, with the other authors named in full); a nice and tedious description of Lord Byron’s arrival in society; every Patroness of Almacks, and various other aristocratic personages, many of whom even get lines. The most notable of these is probably Regency dandy Beau Brummel; Heyer quotes extensively from various anecdotes told of him, or said they happened in this book, which makes Brummel the one fully alive character in the book. It’s meant to create a realistic depiction of the Regency World. But apart from Brummel, much of this rather feels like someone saying, “See! I did research! I really really did!” And it results in something that reads like a dull recital of historical dates and facts, punctured here and there with an unconvincing romance and an equally unconvincing mystery.

Fortunately, Heyer was to greatly improve her ability to create a convincing historical setting (or, perhaps, just regain that ability), and also improve her insertion of mysteries into her Regency novels. But you wouldn’t know that from this book.

#

Heyer could not have known it, but this was the book that would haunt her critical reputation for the rest of her life, and even afterwards. Hearing that the popular writer’s best books were those set in the Regency period, curious critics and readers chose to read the one book with “Regency” in the title—and not surprisingly, wrote Heyer off as a derivative writer too obviously trying to channel Jane Austen, and creating a decidedly lesser effort. The barrage of historical facts and details were, rightly or wrongly, taken as an unsuccessful attempt to add historical verisimilitude, rather than evidence of Heyer’s meticulousness, and the book critiqued as at best inferior Austen, at worst dull and an example of everything that was wrong with popular literature. That Heyer, who dances very close to outright plagiarism of Austen here, later accused two other writers, including the very popular Barbara Cartland, of plagiarizing her work did not necessarily help.

This critical response ignored two factors that could only be discovered by reading other Heyer works: one, she was to completely leave the Jane Austen model, returning to it only slightly in two later books: The Reluctant Widow (which in its mockery of Gothic novels bears a certain resemblance to Northanger Abbey) and The Nonesuch (which follows Austen’s advice by focusing on just a few families in a village, and the social interactions between them.) But although these later books contain a certain Austen influence, and Heyer followed Austen’s example of letting dialogue define her characters, Heyer was never to use an Austen plot again, and indeed was to go further and further away from Austen as she delved deeper into the Regency period. In part this is because Austen created only two heroines who could, before marriage, even consider entering the aristocratic world that Heyer would later create, and neither Emma Woodhouse nor Anne Elliot appear to have much interest in joining the upper ranks of London society. Austen could only provide Heyer with so much inspiration, and indeed, was almost limiting.

And two, Regency Buck, with its general serious tone, is atypical of her Regency novels. Indeed, at least three of Heyer’s Georgian novels (The Convenient Marriage, The Talisman Ring, and Faro’s Daughter) sound more like “Heyer Regency novels” than does Regency Buck. But thanks to the unfortunate title, many readers started here, and went no further, and critics summarized her writing and world building based only on this book. Being a bestseller was already a near kiss of death from (usually male) serious literary critics in the 20th century; being a (seemingly) dull bestseller nailed down the coffin. Later essays by A.J. Byatt did something to push against this reputation, but still led critics and academics to read Regency Buck, flinch, and free. A critical retrospective published in 2001 even noted that more critical and academic attention had been paid to Heyer’s mystery novels, less influencial and less read, than the Regencies that sparked an entire subgenre.

About that subgenre: no one, reading this book, especially after The Convenient Marriage, would have guessed that Heyer would shift the frothy plots and witty dialogue of her Georgian novels to the Regency period, or that she would later convert the world she so dully depicts here into its own universe, complete with its own language and words. Indeed, Heyer would write eight more novels before returning to the Regency period.

Next up: Death in the Stocks, proof that despite this book, she had not lost her ability to write witty dialogue.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida. Follow her Georgette Heyer reread here on Tor.com.

I agree with the Austenesque books you mention, but would also make an argument for _The Grand Sophy_ as being Heyer’s take on Austen’s _Emma_.

This is not a book I reread either although in fairness to Judith and Worth, they both are more intelligent and in Worth’s case, courteous, when we meet them again in _An Infamous Army_. Thanks for the review!

Cassandra

“Regency Buck” is one of the most frustrating books – the heroine is constantly getting herself into messes (despite thinking herself well able to handle everything) and Worth is constantly having to rescue her, while showering her with condescension.

Impossibly annoying.

Its one bright spot is when she rather hilariously meets Brummel. Otherwise, this is definitely one of the lesser Heyers.

@cass — I hadn’t seen that before, but I think you’re absolutely right that The Grand Sophy is Heyer’s take on Emma — the managing heroine that knows best. That said, The Grand Sophy at least has a different plot. Regency Buck, up until the kidnapping, is pretty much the same plot as Pride and Prejudice, with weaker versions of the three major characters.

I can’t think of any direct Heyer analogues for Sense and Sensibility, Persuasion and Mansfield Park, although Heyer certainly drew on Lady Susan for some of her minor characters.

@Andrea K — I know! I don’t think there’s another Heyer heroine who gets into as many disasters/messes — maybe Barbara Childe from An Infamous Army, later, but Barbara doesn’t ask to be rescued and she’s under some major stress. (Maybe that’s why she and Judith become friends. Their propensity to get themselves into bad situations.) Oh, and Tiffany from The Nonesuch, but Tiffany isn’t the heroine, so I don’t think she counts. Otherwise, someone like Judith in an otherwise long line of fairly self sufficient heroines is so irritating. The other heroines who need help generally need it because of inept family members, not their own ineptness.

@beths — Eh, even the Brummel meeting was kinda irritating on this reread, since it just served to show me AGAIN how clueless Judith is, and I spent the rest of the novel thinking, Worth, marry someone with a brain.

The is the only Heyer I’ve read, and it is awful. I hated the whole thing. The sections following her brother around to play some sport or other were so boring and pointness.

But my biggest problem is Worth. Judith tries to figure what’s going on but makes the mistake of taking her ideas to Worth who lies to her repeatedly, telling her it’s all in her head. She’s not strong-willed enough to ignore him and find the truth on her own. Nothing like psychological abuse to go with the sexual to build a strong marriage.

There are so many things I dislike about this book! I can still remember squirming with vicarious mortification on Judith’s behalf when I first read it at the age of twelve. Now, I find a certain flavour of “Ha! You may think you’re the clever one of the family, but the real world will soon cut you down to size!” in the way the Heyer treats Judith.

For me, this book shows the nastier side of English Regency life a bit more than the later ones. I’ve always found it a bit of a cheat that so many Heyer heroes are fine with bareknuckle fistfighting, but don’t follow cockfighting, which mirrors acceptable attitudes in 1930s England, where amateur boxing was still popular in public schools, but cockfighting was totally beyond the pale. I think a real Regency buck would have followed cockfights just as much as fistfights, but even here it’s only Judith’s uncouth deceased father and dim-witted brother who have fighting cocks, and it’s a big warning flag to readers that Bernard Taverner is hanging around a cockpit.

I have very mixed feelings about this book. I don’t love it, but it was the very first Heyer I read and, having read it, I was wild to read all her others. I bought it on a band trip to Winnipeg in the early 1960s. It’s not a book I reread very often, but I have a kind of sentimental fondess for it.

Also, I now live part of the year in Brighton and I keeep a copy in my flat for the descriptions of Brighton and the Pavilion.

It doesn’t bother me at all that it’s deriviative of Jane Austen. The catalog of historical figures doesn’t bother me – it’s kind of fun to read what amounts to gossip about them when some of them are so present here in the history of Brighton.

I don’t like the main characters, though, and I don’t like books where all the drama depends on people not talking to each other or trying to understand each other. And that’s pretty much the entire story, here.

But, I can’t forget that it was my first Heyer. Followed by The Grand Sophy, and Friday’s Child, and The Corinthian (all bought on the same band trip.)

I’m sooooo glad you are going to read Death in the Stocks. I love it.

I think you’re confusing literary criticism with plain and simple ‘I didn’t like it’. If you’re interested in excellent literary criticism, I recommend you check out A.S. Byatt’s work, who as you point out (At least I assume that’s who you mean by ‘A.J. Byatt’..?) was an admirer of Austen, and as a Booker prize winner in her own right, might be said to know a thing or two about the field.

Mea culpa – in my snitty comment, I of course meant ‘an admirer of Heyer’.

I don’t agree with your criticism at all. Regency Buck is superbly written. Heyer brought society to life with her vivid details of the ton. Her dialogue is delightful. And I love how she humanises the otherwise enigmatic Brummell.

The only Regency authors (other than Ms. Austen) to date whom I can read without squirming are Georgette Heyer and Clare Darcy, in that order.

However, Heyer isn’t infallible; the most tedious of her novels I have ever had the misfortune to read is The Toll Gate. My faves: Regency Buck, Devil’s Cub, Friday’s Child and Cotillion.

Hi Leni —

Thanks for your comment.

I own a copy of Georgette Heyer: A Critical Retrospective, which contains a reprint of the A.S. Byatt article. A key phrase from that article (reprinted on page 271 in that book):

“Which brings me back to the “serious” literary-critical dismissal of escape literature.”

In other words, Byatt in her essay said EXACTLY what I am saying here. It’s not that Heyer was disliked. It’s that she was dismissed and ignored by literary critics in the 20th century.

Byatt’s article, which did not appear until 1969, was the first serious literary attention that Heyer received. By that time Heyer had been a writer for 48 years and steady bestseller for 25 years (Friday’s Child appeared in 1944) and had already spawned multiple imitators and at least two plagiarists (one of whom, Barbara Cartland, also became a bestseller). She was popular and influential. And yet, even after Byatt’s article, Heyer continued to be mostly ignored and dismissed by literary critics, as her biographers have documented. And yet she wrote “serious” books.

Heyer’s hardly alone in this — the 20th century is full of women writers attempting to write serious literary works, only to find themselves dismissed as popular, genre, or otherwise “non-literary” authors — often by male critics. This is something A.S. Byatt was definitely aware of. So it’s more than “dislike,” something the article you attempted to quote to me was pointing out.

@Laaleen — It’s ok to disagree with me. I just find the dialogue of Regency Buck — Brummell excepted — as so stilted, not to mention surrounded by lots and lots of tedious things.

We can certainly agree on The Toll Gate, though!

I think Clare Darcy was one of the better Heyer imitators, although I haven’t read her in years.

Interesting how tastes are so different. The Toll Gate (together with Venetia and The Unknown Ajax) is one of my all time favourite Heyers.

The ones I least like are Devil’s Cub, A Convenient Marriage, Friday’s Child and Regency Buck.

1. From my understanding of the Regency Period, Bernard Taverner was poor enough to need to marry into wealth. Maybe not a pauper, but still poor enough to envy and hunger for Judith’s fortune. In the same way, Elizabeth did not need to marry Darcy, a person with much less would have done. She did not refuse Collins because he was not wealthy enough, but because she did not love or respect him. During the time she felt attracted to Wickham, his poverty did not turn her off.

2. Jane Austen’s writings were social commentaries. GH wrote to entertain, and provide as realistic a backdrop as possible for her “flights of fantasy” None of her novels were meant to be, nor were, period drama with realistic scenarios. The fact that “literary critics” did not like GH, only shows how narrow their viewpoint is.

3. One cannot empathise with Judith because she is “rich”? and one empathises with Elizabeth because she is “poor”? The fact that Judith and Worth were social matches as well as well matched financially is a plot failing? Bit of a stretch, that, for me.

4. Why must one hate GH in order to love JA? I have spent 35+ years loving both, and I have never had a problem with the two styles, and attitudes.

4. Why must one hate GH in order to love JA? I have spent 35+ years

loving both, and I have never had a problem with the two styles, and

attitudes.

I think that loving Georgette Heyer’s work is a lot less straightforward than loving Jane Austen’s work. Published over a much longer period, and with so many novels in a number of different genres, Heyer’s body of work is far more uneven. Given that her serious contemporary novels are so hard to find, I doubt if there’s anyone who can say that they’ve read and loved all of Heyer’s works.

My understanding of Austen’s novels has certainly deepened in the forty years since I first read them – in particular, I have a much greater appreciation of the character of Fanny Price in Mansfield Park. But I still love them unreservedly, and probably always will.

My relationship with Heyer’s works is more complicated. Some of the Regency novels I once wrote off as dull are now among my favourites, while some of the more swashbuckling 18th century ones I used to love I now find nearly unreadable. Seeing the level of snobbery and social conservatism in her contemporary mysteries made me reconsider how much of her Regency world reflected the real Regency, and how much was distorted by her bias in what she chose to display, and even more importantly what she chose to leave out.

One thing I reallly enjoy about this series of posts is finding common ground with other readers who, while they love so much of Heyer’s work, can still see flaws and problems. The occasions where I disagree with others’ views have certainly provided food for thought.

@bodhimoments — I think you misread me here. My specific statement was “she [Judith] lacks one major feature that immediately makes Elizabeth sympathetic…” It’s not that wealthy characters can’t be sympathetic. Heyer gave us several — Lady Barbara in An Infamous Army; Jenny in A Civil Contract; Annis and Abigail in their respective books; Serena in Bath Tangle (I’m not overly fond of her but I can certainly see where others would be) and more. And that’s ignoring various side characters.

It’s that Judith isn’t.

Regarding Bernard Taverner — well, sure he wanted to marry up. That was pretty common in his era, both in fiction and real life, and it’s not unheard of for someone already well off to want to be still more well off, through marriage if possible. That’s fine. At the same time, he’s obviously able to move in the upper levels of London society — the very upper levels. He’s hobnobbing with dukes and the sort. He’s able to keep multiple servants and live very well. He has plenty of wealthy friends and acquaintances. He’s not losing his house.

In contrast, Wickham actually had to get a job (something he whines about). He doesn’t have servants; he doesn’t have his own home; he doesn’t have any income from rents. If the war ends, he’s probably in real trouble: as he says, he doesn’t have the money or connections for a church position; he has no legal training. Granted, his biggest problem is that he’s been running around seducing teenagers which is his own fault. But Wickham’s original story (which leaves out the whole I love 16 year olds) is calculated to appeal, and it does, because it’s based on the reality that his current financial position is tenuous. Bernard’s story is also calculated to appeal, but it’s based on a “feel sorry for me! I’m not as wealthy as these SERIOUSLY wealthy people!”

“None of her novels were meant to be, nor were, period drama with realistic scenarios.”

An Infamous Army, the follow-up to this, is period drama with realistic scenarios. So is The Conqueror, Royal Escape, and The Spanish Bride. All four of these were carefully and extensively researched to be as historically accurate as possible.

Later, in the middle of her escapist period, Heyer created realistic scenarios in A Civil Contract, and less obviously in Bath Tangle, Venetia, and Charity Girl. (Charity Girl provides an unrealistic ending to that, but the situation faced by Cherry is real.)

The better question is why, with the arguable exceptions of Venetia and A Civil Contract, did her escapist novels sell so much better? My argument is that her real gift was for comedy. But in her desire to be taken seriously by the literary establishment — and this was a very, very real desire, well documented — she ignored her comedic gifts as she tried to write serious novels. And some of these serious novels, including this one, hurt her critical reputation. (You can see this in Georgette Heyer: A Critical Retrospective.)

Oh, and I certainly enjoy both Georgette Heyer and Jane Austen; I’m recommending many of the Heyer books in this reread. Just not this one :)

@Azara — I was with you right until the defense of Fanny Price!

You know, one of the reviewer’s earlier points was the fact that Judith was an heiress unlike Elizabeth Bennett who had to make a good marriage. The need for women to marry well, or at least acceptably is a main theme of P&P. The fact that Judith has first rate matrimonial prospects takes RB completely out of the running for P&P look alike.

The reviewer latched on to the animosity between Judith and Worth and saw nothing else! Even the fact that Worth had been in love with Judith from the get go and was prevented from acting on it out of honor rather than pride seems to have escaped her.

No doubt Heyer was a fan of Austen but this review goes too far and reveals a very limited understanding of both authors.

Interesting, well informed and perceptive review.

Slightly off topic, picking up on one of your comments, even at fifteen, when I read of that rape threat in ‘Devil’s Cub’ it disgusted me with the man. Even while accepting that the views on rape and threatened rape in Heyer’s era were very different from the ones current now – the idea that a rapist or potential rapist could turn into a romantic love object and an ‘OK’ guy to its victim was horrible to me.

An interesting post. While I agree with many of the points raised, I can’t help but love Regency Buck. It was my second Heyer (read at an impressionable age) and I adore books that bring social history to life, so I found the excess of detail impressive and exciting rather than dull.

Judith is spoiled and headstrong and often unlikeable, I won’t argue with that. Many find her insufferable, but I’m convinced she does change over the course of the novel, especially after her horrible encounter with the Prince Regent. People don’t ever seem to sympathise with her about that event, which I find confusing. Considering her lack of sexual experience, his much higher rank and her attendant confusion, and the constraints of contemporary society, it must have been acutely traumatising. Fainting was the best thing she could have done, and that dawns on her in the carriage later when she cries. As I’ve had a similar experience, I can’t dislike Judith, I simply can’t.

Another great review – being a GH obsessive, I’m so enjoying reading your pieces. I totally agree that the plot is pants: if Bernard wanted to marry money, Judith’s fortune alone would be more than enough. He doesn’t need to murder her brother to add his fortune on top. It makes no sense at all that he goes from being a pleasant, well-mannered man into a raving psychopath.

Whereas Worth starts off so unpleasantly and doesn’t change at all, so why should he be allowed hero status?

I totally agree I have never understood why Heyer excites such admiration, I like An Unknown Ajax, but it’s nothing special. And she was such a snob! Her servants are always portrayed as intellectually inferior. As for her heroes they are often nasty misogynists and her heroines silly and selfish. Having read a book on 19th century can’t which was written by researchers only a few decades after the Recency period, I also suspect she made up some of the phrases she used and does not entirely deserve all the praise she gets for authenticity.

I don’t think it’s quite correct to say that Georgette Heyer never returned to Austen. One of her Regency novels from the early ’50’s, Bath Tangle, makes use of plot elements from several different Austen novels. First, it’s set largely in Bath, like Northanger Abbey and Persuasion.

Second, also like Persuasion, the heroine is pursued by a military officer returning from the War, to whom she was engaged as a teen-ager before they were separated against their will. Getting a second chance at love, they fall into each other’s arms.

The main male character is a guy who might be described as Darcy on steroids. Not merely taciturn and, if crossed, resentful, he’s got an ugly temper (which hides a fairly tender heart). There’s scene at a ball (off-stage, but it’s described by the characters) in which this character, who never dances, asks a a young girl to dance, immediately setting tongues wagging. A deliberate, and pointed, reversal of the Meryton Assembly scene from P&P, it has almost the same affect in terms of the gossip it generates.

There’s an attempted elopement to Scotland (only this time they really are going to Scotland), that the main character has to head off.

There’s a vulgar, but good-hearted, kindly, and rather wise older woman who evokes Mrs. Jennings from S&S.

There’s a scheming mama who’s promoting her daughter into a marriage she doesn’t really want (not too unlike Mrs. Bennet).

And there are probably a half-dozen other Austenish plot elements that, right off-hand, I don’t recall.

Having said all that, I’ll add that, if she uses a lot of the same ingredients, what she comes up with is a dish that’s all her own. Nevertheless, if the dish is original, the Austen influence was, I think, always there.

Wow! What a complete 180 from my own impression of this novel. I adored Regency Buck. It was the first GH book I read and it really brought to life the Regency Era for me in a way that Jane Austen books did not, but that I wished they would have. Now that I have read a multitude of Regency Era books, most written by Marion Chesney, (who I realize wrote RE romance novels, although they are jam packed with historical details and accurate descriptions of the ton), and several other historical non-fiction accounts of the same era, I can honestly say that GH did a wonderful rendition of that time period.

As a side note, having read so much history on this time period, the Regency Era was not one that catered to women. They really were treated like property and if you didn’t have money, you didn’t have much to look forward to. This has made me rethink JA’s works and her reasons for social commentary.

Also, I thoroughly enjoyed reading a book that was published back in the 1930’s. Of course GH writing style and character development would differ from the novels we are used to today. The craft was still being developed. Jane Austen herself writes in an entirely different style than a novel one would read today. While I love all of JA’s works and re-read them all religiously, I still find character development and plot kinks that make utterly no sense. Hello, in Persuasion, is it entirely believable that Anne’s old school friend would have a nurse that just happens to be taking care of a friend of Mr. Elliot’s pregnant (or lately delivered) wife? What are the chances of that happening? Also, look at the cruel way Mr. Churchill takes advantage of Jane Fairfax, who, for all accounts and purposes, is supposed to smarter and more likable than Emma? Mr. Churchill is incredibly cruel and vulgar for praying on the emotions of both girls just so he can channel his emotional angst. Yet, in the end, he gets the girl and excuses himself for his actions by simply saying he was just too much in love and needed the money. Sorry, I don’t buy it. He’s not apt to change.

So, yes, Worth might not change, but Judith, I think, has enough spunk to keep their relationship alive. She’s not going to sit around and worry about worth, she’s going to get in her curricle and ride hell for leather just to show him who’s boss.

Like I said before, this book was everything I enjoyed about Pride and Prejudice and more. Now we know how Elizabeth would have spent the months in between Charlotte Lucas’s marriage and Jane’s trip to London if Elizabeth had been given a chance. She would have enjoyed herself just like Judith, don’t doubt it for one second.

I totally agree with Mari Ness, Heyers Regency Buck is one-dimensional and stereotype, Jane Austens Pride and Prejudice are 3 dimensional and full of life.

The more criticism I read of Heyer, the more I realize I won’t find a critic with whom I agree on everything. So I can accept the different conclusions people reach on her work. Regency Buck, in my opinion, is superb. This author finds Judith an unsympathetic character because she’s rich. I find her sympathetic because of her unusual legal position – which I believe is the point. She’s under the thumb of a man who has essentially attacked her, and she has no recourse.

I strongly disagree about the author’s summation of Worth’s character. He does something horrible at the beginning of the novel, yes. He has to pay for it over and over again, because the woman he falls for understandably detests him. Aside from that, instead of abusing his power over her as guardian (with the exception of the hilarious fight where he insists the only marriage he would countenance is one to him), or repeating his behavior, or declaring his love while in his position, he goes out of his way to be as proper as possible with her. He protects her reputation and sets her up as a success in London. He ensures her choices don’t lead her to harm, he keeps away fortune hunters, and he protects Peregrine from the machinations of their cousin. It has always baffled me how someone could read the novel without seeing that deep love and care he has for her. And as I said, he pays for his initial gross behavior over and over. Nothing manages to banish that first impression (ha! First Impressions) from Judith’s mind, even when he specifically apologizes for it. He is as much cast down by their fight in Cuckfield as she is.

Judith – I can certainly see her faults – but I think Worth is constantly underrated based on his first actions. Actions that, in that era, were not inexplicable or unacceptable. I do remember the first time I read the novel, thinking, “How is he going to come back from this?” and loving the heated arguments between the two, knowing that every barb she sends him hurts him more than she even knows, because he has real feelings for her (whatever those may be – apparently he likes her because she’s feisty and blond).

Regency Buck is not at all Heyer’s best novel. But I think that has to do with her attempts at making it a mystery/romance instead of a straight romance. I like the character of Worth in Regency Buck, but Heyer purposely had to make him appear unlikeable for him to be a credible suspect in the attempts on Peregrine’s life. I think that biases a lot of readers against him and after the big reveal there isn’t enough of the novel left for him to make up that ground. In the end, we find out Worth is a good man: he has been taken with Judith since their first meeting (and its clear he regrets his behavior), does not take advantage of her while he is her guardian, sets her up to be a hit in society, and protects her and her silly brother (both from physical and social harm) in spite of their silliness and distrust. I really like the scene where Worth presents himself to Judith when she is finally of age. He clearly comes looking his best for the occasion with his Weston coat and exquisitely tied cravat. And all Peregrine can talk about is boats. And Worth basically has to buy him a yacht to get him to leave them alone.

I’ve read about this novel’s similarities to Pride and Prejudice before, but it wasn’t obvious to me when I read Regency Buck due to the huge differences both in the plot and in the writing style. This was a novel with poisoned snuff! Even if some of the language is similar, the plot and characters are so, so different.

I would love to read a fan fiction version of this novel where Worth is actually a sociopathic bad guy who is trying to kill Peregrine. I knew that wasn’t going to happen, but what a twist that would have been!

On Georgette Heyer’s coming near to plagiarism, almost nobody seems to know that she lifted all of her wild, sporting young male chaarcters, their slang, activities, the ‘low life’ characters, etc from Pierce Egan’s 1821 Life in London: Or, The Day and Night Scenes of Jerry Hawthorne, Esq. and his Elegant Friend Corinthian Tom, accompanied by Bob Logic, the Oxonian, in Their Rambles and Sprees Through the Metropolis..’

‘Chits’, ‘Cits, ‘Prime Articles’ ‘, you name it.

@@@@@ 27, Jessie

On Georgette Heyer’s coming near to plagiarism, almost nobody seems to know that she lifted all of her wild, sporting young male chaarcters, their slang, activities, the ‘low life’ characters, etc from Pierce Egan’s 1821 Life in London: Or, The Day and Night Scenes of Jerry Hawthorne, Esq. and his Elegant Friend Corinthian Tom, accompanied by Bob Logic, the Oxonian, in Their Rambles and Sprees Through the Metropolis..’

‘Chits’, ‘Cits, ‘Prime Articles’ ‘, you name it.

Pierce Egan is in no position to cry “plagiarism!”

The Life in London characters were invented by the artists and satirists, Robert and George Cruikshank. They were published as broadsides, and were all the rage. Eventually they were made into a book, which is where we mostly know the series from. Bob and Jerry’s popularity skyrocketed when they appeared on stage. The Cruikshanks invited their friend Pierce Egan to provide captions for their illustrations.

Pierce Egan was a journalist who covered the sporting world. Much of the slang Jessie credits to Egan was the real life language of fisticuffs, horse racing, bull and bear baiting, cockfights, and such entertainments. We know that from other contemporary sources. Including other sports reports “He drew his cork, and the claret flowed freely!” Not to mention the knock-off series, John Badcock’s Real Life in London: Or, The Rambles and Adventures of Bob Tallyho, Esq., and His Cousin, the Hon. Tom Dashall, through the Metropolis. Francis Grose’s 1811 Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue would have been at least as important.

I don’t regard Heyer’s use of such sources as plagiarism. I call it legitimate research.

Pierce Egan was a journalist who covered the sporting world. Much of the slang Jessie credits to Egan was the real life language of fisticuffs, horse racing, bull and bear baiting, cockfights, and such entertainments. We know that from other contemporary sources. Including other sports reports “He drew his cork, and the claret flowed freely!”

Fernhunter:

Thank you for providing those facts, though I did know them already . Certainly, Pierce Egan was a sports journalist and that the terms he used were common sporting slang here in the UK at the time. I read his – appallingly written – book ‘Boxiana’ many years before I read ‘Life in London’.

This article sums up my own view of the unfortunate influence of Heyer regarding the trivialisation of popular understanding of the Regency era.

[[https://mmbennetts.wordpress.com/2009/06/24/what-do-i-think-about/]]

I’m afraid my post came out truncated. Sorry, everyone. This is the full post.

Fernhunter:

Thank you for providing those facts, though I did know them already. I certainly did not imagine that Pierce Egan invented the language in ‘Life in London’ .He was, as you say, a ‘sports journalist’ and the terms he used were common sporting slang here in the UK at the time. I read his – appallingly written – book ‘Boxiana’ many years before I read ‘Life in London’.

Yes, the book was based on the Cruikshank cartoons and there seems to have been some dispute about whose idea it originally was (I believe Cruikshank had the same sort of dispute with Harrison Ainsworth over his ‘Jack Sheppard’).

I have also come across the imitations of ‘life in London’. There being no copyright in that era, no plagiarism was possible.

Whether or not one regards borrowing extensively from an earlier work of fiction without any formal acknowledgement was or wasn’t legitimate research is a matter about which people will have different opinions, of course.

This article by the late writer MM Bennetts sums up m own view of the unfortunate influence of Heyer in trivialising the popular understanding of the Regency era UK (which was a time of great social upheaval and suffering), which is surely a more serious matter:

[[ https://mmbennetts.wordpress.com/2009/06/24/what-do-i-think-about/%5D%5D

Funny, I see Regency Buck is being a much more successful book than you do. To me what makes it good — and what makes a lot of Heyer good — is that it portrays not idealized romance and anodyne characters, but love as it actually happens between flawed people in a messy world.

Neither Worth nor Judith is the kind of paragon usually portrayed in romance novels. They are both extremely domineering and sharp-tongued personalities. So of course they soon spiral into an endless round of snarky one-up-manship.

Personally I actually really enjoy BOTH characters — in the same sense that I have enjoyed some very difficult personalities in real life. Doesn’t anyone else have friends or colleagues who are rude, obnoxious, overbearing, or ridiculously prone to stirring up drama … and yet somehow you continue to value and respect them because underneath all the surface obnoxiousness they are honest and honorable when it really counts? You know that no matter how much they annoy you day to day they will not be fair weather friends. Plus it’s always an adventure to see what snarky thing they’re going to say next.

This is also blessedly not a book in which EITHER main character reforms or has a life changing moment of self-realization. And that’s the true dividing line for me between Austen and Heyer. Jane Austen believes people can change — and dammit, by the end of the novel they WILL change if she has anything to say about it! Georgette Heyer in contrast believes that people almost never change, not even for love. And you know what? Although Austen is the better writer … Heyer is NOT wrong about this!!

Finally, I think there’s something to be said –albeit uncomfortably — for the sexual politics of Georgette Heyer. Unlike the denial or glorification of sexual assault by some romance writers, Heyer portrays it as awful … and ubiquitous. And it’s particularly ubiquitous in this book, where the risk of sexual assault is a constant background noise.

Above all I think one cannot understate the importance of the appalling scene with the Prince Regent in the yellow room. This whole scene — including Worth’s initial impulse to yell at Judith for going off alone with the Prince Regent AND Judith’s ashamed denial that anything happened — is one of the most realistic sexual assault descriptions I’ve ever read in a novel. Heyer totally nails the self-justifying lies of the perp, the confusion and shame of the victim, and the way that even people who protect and care about the victim can all too easily slip into victim-blaming lectures. This is how perps, victims, and victims’ families truly do act much of the time — even today when we think we’re so much more liberated.

And really … what chutzpah Heyer had to openly depict the Prince Regent on-stage as an out-and-out sexual predator!

Viewed in light of this scene — and many others where men are super creepy toward Judith — Worth’s “sexual assault” in the opening chapter becomes much less black and white. From his (admittedly dated and patriarchal) perspective he’s driving back from a boxing match, knowing that a horde of drunken louts is about to throng down the road, and he sees a lone girl who absolutely and unequivocally needs to get off that road for her own safety. He tells her to do this, but because he is condescending and obnoxious she understandably refuses. Then he forcibly makes her do it. He does steal a kiss while getting her home safely. But only when she refuses to practice punching him while he’s teaching her how to punch properly. And why does she need to learn that? So that she can do a better job of defending herself against importuning males — including him!

This is a truly brilliant scene, no matter how much we may bridle at the implied patriarchy. It puts the theme of women moving into male spaces front and center — and establishes the tension between claiming male freedoms versus risking rape by flaunting social mores. This is the theme of the whole book, so it’s great craftsmanship to sum it up so vividly. This scene also sets the tone for Worth’s conduct toward Judith throughout the novel. He is overtly sexually interested in her and in no way shy about showing it — and yet at the same time as he’s stealing a kiss he also gives her the tools to combat unwanted sexual overtures.

Worth will repeat this pattern again and again — with horses, snuff, etc. He excludes Judith from the male world in some ways — yet he also opens the door much wider than any other man in the book is willing to do. He wants her to be powerful. He’s quite explicit that he is attracted to her masculinity and assertiveness. And yet he also wants to dominate her sometimes. There is something very complicated and rather interesting going on here.

This type of man — sexually fascinated by strong women yet also needing to reassure himself by dominating them at least in some areas — is certainly still with us today. Albeit in slightly subtler forms. Or maybe not really that much subtler!

Just to be clear, I am not saying I’m always comfortable with Heyer’s sexual politics. They’re often appalling. But I do think she was in some ways ahead of her times … even, in some ways, ahead of OUR times. In 2019 it is still very, very hard to find regency novels that acknowledge as frankly as Heyer did that the stereotypical “rake” who was “irresistible” to women was often simply a very successful, socially accepted sexual predator. Heyer, in contrast, was all over it.

So that’s my defense of Regency Buck. The protagonists are both obnoxious pains in the butt. The whole book is kind of rapey and creepy. But you know what? People ARE obnoxious and flawed. And life is rapey and creepy. And where is it written that romance novels need to make life simpler and less messy than it really is?