There’s a lovely scene in “Errantry,” the title story of Elizabeth Hand’s newest collection of short fiction, in which a character finds a print of a painting she loved as a child and describes what she used to imagine about the world it depicts: “A sense of immanence and urgency, of simple things […] charged with an expectant, slightly sinister meaning I couldn’t grasp but still felt, even as a kid.”

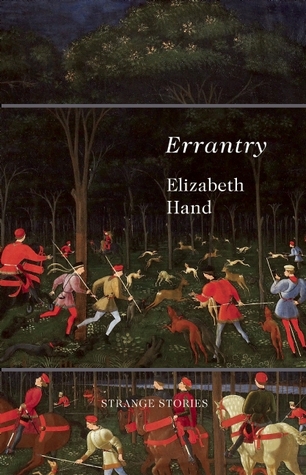

It’s probably not a coincidence that the same painting graces the cover of the book, because that quote is a perfect way to encapsulate the atmosphere of many of the “Strange Stories” in Errantry. The magic in Elizabeth Hand’s short fiction can usually be found at its edges, just slightly out of reach. It’s there for a moment, but it’s hard to see without squinting. If you blink, it might be gone—but you’d never lose the sense that it’s still there, pushing in on reality from the outside.

These are stories of the overwhelmingly mystical breaking into our world in small, almost unnoticeable ways, seen from the point of view of the few people who get to witness those minor intrusions and who then have to try and process their meanings. The subtlety is deceptive: there’s something huge going on, but it’s as if we and these characters are peeking at it through a keyhole, only seeing a small glimpse of what’s on the other side and only being hit by a small portion of the light it sheds. The suggestion that that door may open further is only part of what gives these stories their “slightly sinister” atmosphere.

The nature of Elizabeth Hand’s characters contributes to that edge. The people who experience those vague, confusing hints of magic are usually slightly broken individuals, often coping with a major change of life or about to experience one. In “Near Zennor,” the main character’s wife just died. In “The Far Shore,” a man who already lost the ability to dance is fired from his position as a ballet instructor. In “The Maiden Flight of McCauley’s Bellerophon,” a key character’s old lover is terminally ill. Loss is a theme popping up again and again in these stories, and often the coping mechanism is a short journey: a step outside of the familiar environment that brings that slightly broken person to a far stranger situation than they expected.

But as to what really happens on that intersection of the real and the mystical, explanations are rarely forthcoming. All we get are traces, suggestions, remnants. Hints are strewn throughout the stories, offering tantalizing glimpses of what may or may not be going on, but even if the witnesses could lift the veil and explain those secrets, it’s virtually certain that no one would believe them. Are their losses compounded by that inability to explain, or does the hint of magic help the healing process? The end result is almost always, and in more ways than one, ambiguous.

Elizabeth Hand is one of those authors who can create fascinating characters and environments whether she’s working in the longer novella format (see: the Hugo-nominated “The Maiden Flight of McCauley’s Bellerophon” and “Near Zennor”) or in just a few pages of short story. “Cruel Up North” and especially “Summerteeth” (maybe my favorite piece in this entire collection) cram an amazing amount of meaning and impact into just a few pages, turning them into stories you’ll want to read more than a few times. The novellas and novelettes allow more room to build and expand, making their characters and plots more instantly accessible and rewarding, but it’s in the density of the shorter pieces that Elizabeth Hand really shines.

If there’s one piece that Errantry: Strange Stories could have done without, it’s “The Return of the Fire Witch”, which was originally included in the Jack Vance tribute anthology Songs of the Dying Earth. Don’t get me wrong: it’s a wonderful story that fit perfectly well into that anthology and did Jack Vance proud, but it feels ridiculously out of place here. There’s a certain flow to Errantry, the same kind of rhythm that makes a great album more than just a collection of songs. Many of these stories have a common atmosphere, or recurring settings, or shared themes and images that echo back and forth across the collection. As hilarious and well-executed as “The Return of the Fire Witch” is, it sticks out like a sore thumb compared to the other nine stories.

However, that’s really the only minor complaint I can come up with when it comes to Errantry, because, taken as a whole, Elizabeth Hand’s latest collection is a gorgeous set of stories. It’s tough to review a book like this one, because avoiding generalization is almost impossible. Each of these stories really deserves its own separate write-up.

So. In “Near Zennor”, the main character is at one point is looking at a sparse landscape from a moving train: “again and again, groves of gnarled oaks that underscored the absence of great forests in a landscape that had been scoured of trees thousands of years ago. It was beautiful yet also slightly disturbing, like watching an underpopulated, narratively fractured silent movie that played across the train window.” A beautiful image, and a great summation of what it feels like to read these stories.

Stefan Raets reads and reviews science fiction and fantasy whenever he isn’t distracted by less important things like eating and sleeping. His website is Far Beyond Reality.