“I don’t mind at all,” I said. “It doesn’t matter who you are or what you look like as long as somebody loves you.”

After the tragic death of his parents in a car accident when he is only seven, the narrator, who never does get a name in the book, is sent to live with his Norwegian grandmother, first in Norway and then in England. Echoing Dahl’s own relationship with his Norwegian relatives, they speak both English and Norwegian to each other, hardly noticing what language they are using.

The grandmother is both a wonderfully reassuring and terrifying figure: reassuring, because she loves her grandson deeply and works to soften the horrible loss of his parents, with plenty of hugs and affection and tears. Terrifying, mostly because after he comes to live with her, she spends her time terrifying him with stories about witches, stories she insists are absolutely true, and partly because she spends her time smoking large cigars. She encourages her young grandson to follow her example, on the basis that people who smoke cigars never get colds. I’m pretty sure that’s medically invalid, a point only emphasized when the grandmother later comes down with pneumonia, which, ok, technically speaking isn’t a cold, but is hardly an advertisement for the health benefits of large cigars. (Not to mention the lung cancer risks.)

But if she is not exactly trustworthy on the subject of cigars, she does seem to know her witches quite well. Her stories are terrifying, especially the story of the girl who vanishes, only to reappear in a painting, where she slowly ages but never seems to move. Gulp. That’s pretty effective witchcraft. She also lists the distinguishing characteristics of witches for her grandson: baldness, widely spread feet with no toes, always wearing gloves to conceal the claws they have in place of fingernails, and so on. The large problem with this, as the grandson and most readers immediately notice, is that most of these differences are easy to conceal (and quite a few people may find the discussion of baldness in women disturbing; this is not a good book for cancer survivors to read.) I’ll also add that many women with widely spread toes regularly jam their feet into shoes with pointed toes, so this particular identification method seems quite questionable. I suspect also that many parents will not be thrilled by the book’s “you’re safer from witches if you never take a bath” message.

The grandmother has gained this knowledge, as it turns out, from years of hunting for the Grand High Witch without success. The witch is simply too powerful and wealthy to be found. The same cannot exactly be said for the witches of England, one of whom the protagonist finds within weeks of his return. After a hurried consultation he and his grandmother decide not to fight the witch, but it’s perhaps not that surprising when she falls very ill with pneumonia shortly after that (don’t smoke cigars, kids, really).

The rest of the witches of England are hiding under the name of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, which seems respectable enough until the Grand High Witch makes her appearance, noting that all of the children of England need to be eliminated, like, now. (Some of you may be sympathizing.) The witches are initially horrified. Not, I hasten to add, because they’re against the concept, but because it’s a pretty daunting task. But after the Grand High Witch explains her plan, they grow enthusiastic.

I must say that the plan seems a bit needlessly complex to me: the Grand High Witch intends to have every witch leave her job and open a candy store, then give free candy to every child who enters so that the kids can be transformed into mice and caught by mouse traps. Surely these very wealthy witches, capable of developing sophisticated masks and disguises and finding all kinds of rare items can think of something better than this?

Complicated or not, the first part of the plan does work on the first two kids they try it on, a not-particularly-nice kid called Bruno Jenkins and our narrator, who now find themselves transformed into talking mice. Both of them are remarkably calm about this—after all, getting turned into mice means not having to go to school, plus, you still get to eat (which in Bruno’s case makes up for a lot.) And, as the narrator soon learns, this still means lots of adventures—even if, in a nice nod to the nursery rhyme, your tail gets cut off by a carving knife.

It’s all magical and tense and, somewhat unusually for Dahl, tightly plotted. The matter of fact tone used by the narrator—similar to the one Dahl used for Danny the Champion of the World—manages to add to the horror of the moments when the narrator confronts the witches, and even before then. This is one Dahl book where I found myself genuinely anxious for the protagonist. Dahl’s portrayal of the distinctly individualistic grandmother, with her enjoyment of Norwegian folk tales and fierce love for her grandchild, not to mention her marvelous confrontation with Bruno’s parents later in the book, is beautifully done, as is the relationship between grandmother and grandson. Some might even find themselves a bit weepy at one or two parts. And the overarching lesson that it’s what inside that matters, not appearances, whether you are a nice looking woman who is secretly a witch or a mouse who is secretly a boy, is all very nice, as is the related message to never trust in appearances. And I had to love the idea that even if your exterior form changes, you can still do things. Amazing things.

Nonetheless, the book leaves me a bit uneasy.

It’s not the misogyny, exactly, especially since I’m not sure the book deserves all the vitriol sent its way on that basis. Certainly, Dahl begins the book by telling us that all witches are women, and all witches are evil. He softens this slightly by adding that “Most women are lovely,” and that ghouls are always men, but then counters the softening by noting that witches are more terrifying than ghouls. He later states that only boys keep pet mice, and girls never do, a statement not borne out by my personal experience, but in some fairness this is not the statement of the narrator but rather that of the Grand High Witch, who may not exactly be an expert on the types of pets loved by small children.

More problematic are the more subtle statements later in the book. The witches, as the grandmother carefully explains, are almost impossible to distinguish from ordinary women, meaning that—as the narrator warns child readers—pretty much any woman could be a witch. That’s a problem, not helped when we later discover that all of the witches of England are well to do, professional women with successful careers who engage in charity work. The Grand High Witch is even well known as a “kindly and very wealthy baroness who gave large sums of money to charity.” (Ok, baroness isn’t a profession exactly, but the other witches work in professional positions, and even the Grand High Witch worked to gain her large amounts of money.)

The implication, of course, is that even the most kindly, generous women may be hiding their secret evil selves behind masks; that even the most kindly, charitable woman may be plotting to destroy or transform children. And the off-handed observation that many of these hidden witches are professional, wealthy women does not help. Oh, sure, the Grand High Witch is presented as an aristocrat who probably inherited at least some of her money, so not exactly the most sympathetic creature, but she’s also presented as someone who works very hard at organizing witches and conventions and developing potions and making magical money—much of which, to repeat, the text tells us she gives away. We aren’t told as much about the other women, but if the Grand High Witch can be trusted (and perhaps she can not) they all have successful careers and businesses.

Countering this, of course, is the grandmother, as well as a kindly neighbor who makes a brief appearance in the story and then disappears. An elderly woman as the hero of a children’s story, and especially a children’s story featuring a boy, is great. But the positive joy she and her grandson take in the thought of destroying the witches is a bit stomach churning, even if the process is going to involve a lot of international travel and adventures. Not to mention that I question their assumption that cats will be very willing to help out. Oh, yes, many cats enjoy catching and playing with mice, but many cats also enjoy taking long naps and sitting on computer keyboards. You get what I’m saying.

Which leads me to my other problem with the novel: the end.

In the last chapters, the grandmother explains that since mice have short lives, the mouse grandson will not live very long—a bit longer than most mice, but not that much longer. Perhaps eight or nine years at most. The mouse grandson tells her, and the readers, that this is fine. Not because he’s pleased to have sacrificed himself to save the children of England—in fact, he complains that they have not done enough to stop the witches. But because he doesn’t want to face the thought of living without his grandmother, who probably has about the same amount of time to live.

It’s all very touching, and an understandable position for a child to take, particularly a child who has already lost both parents, doesn’t seem to have any friends, and is, well, a mouse. (The witches never created an anti-mouse transformation spell, and it doesn’t seem to occur to either grandmother or grandson to try to create one. Maybe only witches can.) For that matter, the “I don’t want to live without you” is a position often taken by adults.

But the narrator is a nine year old kid, who hardly knows what he’s missing.

Am I wrong to read too much into this? Possibly. Kids and young adults die every day, often bravely accepting their fate. But it seems odd for the narrator not to express any anger about this whatsoever—even towards the witches—and instead be grateful for his upcoming death for this particular reason. Of course, he is going to get a lot of adventures along the way first. And this is, at it’s heart, a novel about accepting change.

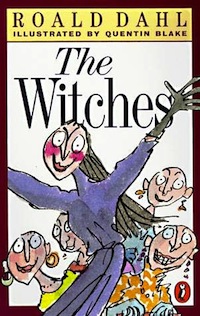

The Witches is arguably the Roald Dahl book most frequently banned in American libraries. I’m against banning books in principle, and I wouldn’t hesitate to give this book to a child—but I would certainly want to discuss its implications with the kid afterwards.

Mari Ness assures you that she is not a witch, despite the presence of two suspiciously witchlike cats. She lives in central Florida.

All I can think of is what it is like to be seen as a child-molesting pervert because you are a man and: a) a scout leader, b) a member of clergy, c) anywhere near a school or playground, and/or d) alive.

“Because he’s portraying something in fiction, he MUST BE ADVOCATING IT IN REAL LIFE!” is an attitude far, far too many you Tor.com columnists have.

Or maybe he just thought it was a good, gruesome story?

Yeesh.

@Rancho Unicorno — I must admit that my first response to your comment was to think that I’d be a lot more disturbed if an undead priest showed up someplace near a playground…

But your point is well taken, and might be some of what I’m reacting to here. Thanks very much for making me think a lot more.

@Earl Rogers — Not sure where in the post I use the word “advocate.”

I’ll admit that I find the complaint that the witches are all “well to do, professional women with successful careers who engage in charity work” to be a bit bizarre. Would you have preferred that they included more homeless women in their numbers? Or if they did that, would you be complaining about the unfortunate implications of stereotyping the poor?

Regardless, the social position of the witches is almost necessary for this conspiracy-type story. The idea is that “they could be anywhere,” but in practice, “anywhere” needs to be pretty close to the protagonist (and the audience) in both physical and social terms. If you want to terrify the middle class kids who are going to be reading your book (and it definitely seemed Dahl did), you need to make the witches the sorts of people that they come into contact with frequently and would be inclined to trust.

Overall, though, I’ve got to agree that this one is pretty disturbing. Unlike you, I think I would hesitate before giving it to a child. I wouldn’t necessarily say, “No,” but I would have to think about the specific kid and whether I was broadening horizons or just feeding him nightmare fuel.

@Lsana — Expecting homeless women? No, just perhaps expecting a bit more of a range in the social classes of the witches, because as it is the book comes off to me as faintly hostile towards successful professional women. I might also be reacting this way because this feels new for Dahl, who had shown working women in very positive lights in earlier books, and would look at the issue more directly in Matilda.

Your point that the “anywhere” needs to be pretty close to the protagonist/readers in physical/social terms is spot on, but I’ll also note that the witches themselves don’t think they are in close enough contact with children or in positions where they would come into contact with children frequently enough for children to come to trust them. Thus the plan to abandon their jobs for candy stores. They aren’t trusted by/met by children now, but as candy store owners, they will be. It’s also kinda odd that the candy loving Dahl suddenly takes a “BE CAREFUL OF CANDY” approach here.

….and you know, I think I’ve just realized another reason why I’m uneasy about this book. It has all of the gruesomeness I expect from a Dahl book, but in other ways it’s a major departure.

I’ve noticed this before: when a reviewer points out disturbing or problematic parts of a work, someone leaps up to defend the author on the grounds that the author wasn’t advocating those things and they’re just part of the story. It seems to me to profoundly miss the point.

One of the main points of a review is to describe a work well enough for someone else to decide whether or not they want to read it. (There are others, of course, but I think that’s a big one.) Disturbing or problematic elements don’t have to be intentional to be disturbing or problematic. The author’s intent can be quite interesting from some angles of literary criticism, but it seems rather beside the point when the question is whether a reader might enjoy it. Whether intentional or not, those are aspects that may turn off or annoy a reader, thus making a book less fun to read. And I’d like to hope that we read, at least in part, for fun! Particularly children’s literature!

Observation is not accusation. Moral culpability is not only usually not implied, it’s usually not even relevant. Dahl is no longer alive, and even if he were, the work isn’t going to change at this point. It is what it is, regardless of what Dahl intended when he wrote it. Everyone will have their own reactions to that work, and part of the goal of a reviewer is to explain their personal reaction to the work in enough detail that people can use that both to judge the work as a candidate for their own free time (taking into account how much they do or don’t care about the same things as the reviewer) and to find interesting things to talk about.

The movie version of this scarred me til I was about 12, I was taller and stronger than most of my friends and did martial arts, but if I wasn’t with someone I was crippled with fear that the witches were everywhere, even with my dad or grandma around I found it hard to even go into my basement, and the only teacher I felt comfortable around was my guy teacher in 5th grade. Now I’m fine and its sort of funny but holy shit am I never letting my kids read this book or see the movie once they’re born, and I hate censoring things as well

I find it very interesting that there’s no mention in this review that this is a Jim Henson film who was largely responsible for getting it made. No Strings Attached: The Inside Story of Jim Henson’s Creature Shop devotes several pages to the makeup done for this film.

And yes, the witches here are really, really scary.

@Nicholas Winter — The reason there is no mention that this is a Jim Henson film is because this is a review of the book, not the film.

A review of the film will be coming up next month, once we’re done with the books. Which…actually I think there’s only two more book posts to go!

@rra — Thank you.

@Greyfalconway — I can certainly understand how you’d want your kids to avoid that experience!

The tale of the girl who disappeared and ended up in a picture still gives me the chills to this day when I remember it…

Aah, the book (and in particular – the movie) that gave me a fear of witches so bad that even the movei, Hocus Pocus gave me nightmares for ages.

I still actively avoid anything witch related.

Good childhood memories…. I think…

As a parent, I’m comfortable with any child over five reading that as a safe and delicious transgression rather than advice to take to heart.

I think a lot of this is the difference between how kids read things and how adults do. Like you, I was aghast as an adult that the narrator lost his entire adulthood, but for kids it’s not as big a deal — already to them all of adulthood feels like a foreign land where they are replaced by an alien version of themselves. So it’s a very interesting appeal to kids on their own level. It’s a fun book to read with a mixed age book group, just to get the different takes on the dangers and the losses.

But as a parent, I’d keep an eye one kids who are reading/have just read it. Because Dahl is so good at writing to kids on their level, he’s also very good at inspiring deep terror, and not always in an obvious way.