“So I heard that you won Tumblr,” a coworker joked with me the other day.

He was referring to the maelstrom of activity that was triggered when I posted about my con harassment experience at New York Comic Con by the film crew of the YouTube web series Man Banter, hosted by Mike Babchik. I won’t reiterate everything that happened, but kept pretty good documentation. Other industry professionals and geek news sources had done the same, too. There is a petition out, created by the activist group 18 Million Rising in order to hold Babchik’s employer, Sirius XM Radio, accountable for his actions since Babchik had gotten into the convention using his job credentials. Since the incident happened, New York Comic Con had assured that they will tighten their safety policies, and I even had a nice wrap-up interview about making convention spaces safer with NYCC show manager Lance Fensterman.

Okay, that ugly event got all wrapped up with a nice li’l bow of resolution; we can leave this in the fandom corner until the next big misogynistic thing that happens to women at conventions hits the fan (but oh wait, it just did as I typed this). At this moment, I feel like I can voice something that I’ve been holding in this whole time: I am lucky. And it shouldn’t have to be that way.

Everything worked out in a best-case scenario: calling out my harassers actually resulted in them getting punished for their actions without any retribution from them or their supporters. On the eve of traveling to another convention, I feel relatively safe (greatly enforced by that convention’s extremely prominent anti-harassment policies).

For the last two weeks, I had been very angry and determined to fight back against what had happened to me and other con-goers at NYCC. Yet I had also been afraid. It’s a complicated fear, going beyond the ones about retaliation, trolls, flamers, and anon hate. I’m hesitant even as I type this in public, because so much of my actions in this situation had been framed as “courageous” and trotted out as an example of what women should be doing. I’m not 100% comfortable with being the poster child of that narrative.

Unpacking the roots of this fear, though, is important—not only for me, but to have other people understand the situation women and marginalized folk are going through in fandom when it comes to reporting harassment, bullying, and abuse.*

*When I say “women and other marginalized folk,” I mean people of all types: racial/ethnic minorities, people of different abilities and sizes, queer people. I know someone will mention, “But straight, white cis-men get harassed too!” and that is true. In order to raise social standards to protect all people, however, we have to focus on the needs of those who are most vulnerable first. In the greater world, straight, white cis-men have most of the social and political power to fight back against things thrown their way, unlike the rest of us.

One of the big messages that this conversation has promoted is that “speaking out” against your own harassment is key to ensure the safety of an event. Reporting, however, does not necessarily ensure the safety of the victim. For example, a few weeks before the NYCC harassment, a trans* woman spoke out about her treatment at a gaming conference, and the results were pretty terrifying:

“People tracked down my phone number. Hate flooded my work inbox. I had people threatening to track me down in person and attack me. People found my old identity and began to try to publicize it. I faced the darkest aspects of the Internet just for existing and speaking up….I am usually the first to discuss trans issues within the gaming industry, but a few days of death threats can really limit one’s will to fight. All I wanted to do was tell someone that he had upset me. I never wanted anything else.”

“How will I be treated?” was the first reaction I had before I wrote that Tumblr post at 1 AM. I wanted to report this to the authorities, but even as I was gathering information and writing my public warning, doubts flooded my mind:

- Will people believe me?

- Will people reject the seriousness of the issue because “I’m oversensitive”?

- Will people dismiss me for “not having a sense of humor”?

- Will people tell me that if I dressed differently, this wouldn’t have happened?

- Will people tell me that if I had a male friend with me, this wouldn’t have happened?

- Will people try to get ahold of my work or personal information in order to further harass me?

- Will people try to leak my personal information in order to get others to further harass me?

- Will I face negative consequences from NYCC, other conventions, or other industry professionals that could damage my career?

I’m explaining my thought process as an example what many women and other marginalized folk think even before they decide to report anything (if they ever do). Those victims who remain silent aren’t doing it out of cowardice, but out of fear, and those fears are fully justified. I don’t want my story to be held up to critique another’s silence if they need to protect themselves first.

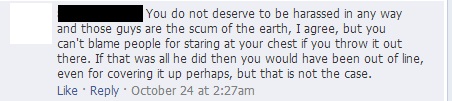

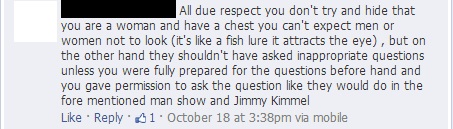

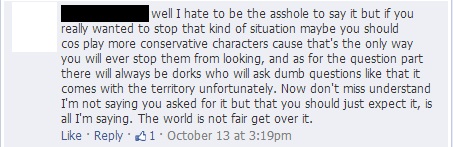

In fact, when cosplayer Bethany Maddock warned people about her harassment at NYCC on Facebook, she faced a variety of dismissive and victim-blaming comments from her followers:

I think if our both cases hadn’t been made public, then it would’ve been harder to convince the convention that what had happened wasn’t an isolated event that could be ignored or the unfortunate result of one guy’s “bad social skills” (which is terrible misconception that Jared Axelrod debunks quite nicely). Victims of harassment are targeted for one reason only: because the harassers want to target them. Enforcing a culture of “Victims Must Report!” as the only solution to harassment, however, could be used to further shame those who remain silent or blame them for being complicit in their own hurt.

The best reaction in cases of harassment, whether told privately to you or heard publicly, is to respect the victim’s wishes. That may be the hardest of all if you don’t personally agree with them, but it is also the most supportive you can be. If they speak up, support them. If they stay silent, support them. If they need to leave the space or the community where it had occurred, support them. Imposing your priorities upon a victim’s situation won’t help them live their life or move on afterwards.

There are other ways that fandom can be proactive that don’t place the onus of responsibility on the victim of harassment. Conventions need to have clearly-stated public policies against harassment and also include procedures of what will happen to those who violate it. A few months back, John Scalzi made a statement that he would not attend a convention that doesn’t supply one and created a thread that over 1,000 industry professionals and fans have co-signed in support. This prioritizes how community safety is everyone’s responsibility. There are also fan-created “watchdog” groups who monitor safety at conventions, such as the Back-up Project, Cosplay is Not Consent, The Order of the White Feather, and SFFEquality. Most importantly, though, we need to have a conversation about what it means to respect all the individuals within a community and not hide behind our geek identities as excuses to justify treating others badly. And we must promote the idea that perpetrators be held fully accountable for their actions.

18 Million Rising’s petition can be signed here; as of this morning, they need less than 250 more signatures to reach their goal. I’d also be interested in sharing ideas about creating safer convention spaces (or any geek space!) in the comments below.

Ay-leen the Peacemaker works at Tor Books, runs the multicultural steampunk blog Beyond Victoriana, pens academic things, and tweets. She also is a professional lecturer who travels across the United States and speaks about steampunk, fandom, and social issues. Her latest writing can be found in Anatomy of Steampunk: The Fashion of Victorian Futurism.

Strangely, what bothered me the most was that you felt you had to qualify how you were dressing in your tumblr post. It shouldn’t matter, but it does, doesn’t it? :(

Thanks for the post, it’s good you’re getting the word out. One of my best friends is a big gamer, and she loves Cosplaying, and traveling to different Cons. Knowing that this potential is out there for her, sickens me. Definitely signing the petition. People need to know that this isn’t okay.

If someone has a TV camera crew with them, the excuse of “socially awkward dork” is not really going to apply.

Did anyone else watch Fangasm? I like that they addressed the con harassment, but was a rather mad at Molly when she told Mike “he didn’t understand.” Sorry sweetie, pretty sure he’s had his own issues and demons.

Thank you for writing this.

(And yes, there is a space at the end of the link that Braid_Tug mentions.)

Unfortunately unable to sign the petition as it won’t accept UK postal codes instead of zip codes.

Jackson Katz gave a TED talk about harassment that opened my eyes to a very important sociatal aproach. As you have so clearly pointed out, it is very difficult for the victim to confront the abuser. There is another angle, one that I think needs more awareness, that of the empowered bystander.

http://www.jacksonkatz.com/wmcd.html

http://www.ted.com/talks/jackson_katz_violence_against_women_it_s_a_men_s_issue.html

I don’t know what’s the matter with your link to the Tess Fowler story, but it gave me a 404 error. This is the link I found through searching.

http://www.bleedingcool.com/2013/10/28/tess-fowler-and-modern-day-misogyny-in-the-comics-industry

I stopped reading when you mentioned the trans person at Eurogamer Expo.

This was what she claimed at first:

And it is a lie. Why do you think she had to fully retract the statement later on?

Did you know that the comedian she lied about also received death treaths?

This is from her adventures at Overclockers.

This is from an interview with Millward (the commedian):

Regarding the Tess Fowler article (linked at “oh wait, it just did”), we’ve replaced it and it should be working now. Here it is again, just in case:

Tess Fowler and Modern Day Misogyny in the Comics Industry.

I really agree that the best response in all cases is to “respect the wishes of the victim.” I have been supportive in many ways to people I have known that have been harassed, and I have had my own situations to deal with. Thank you for this article.

Back, now that I finished the article.

I guess it gives me some hope that these issues or becoming more prominent. But maybe I’m blinkered, because I tend to only follow geek sites that engage in this critique.

I am glad you are bringing this issue to light, and I hope it spreads to the wider cosplay community, so that harassment in any form is no longer tolerated, especially as someone who has been harassed by a couple of chronic bullies in the steampunk community.

@8 Bigerich That someone cried “wolf” does not mean there are no wolves and shouldn’t be used as a cop out.

As someone who used to work cons for a dealer, overseeing mostly young women, harassment happened daily to multiple people. I made sure to tell them before the doors open that it WOULD happen, and that when it did, to get me, and I would deal with the harasser. That we always when to and from the dealer’s room together. That you never told a customer when you were going on break EVER (and they WOULD ask). That was in the days before any cons even had harassment policies to cover specifically sexual harassment.

I had older men try to grab, grope or talk sexually to obviously underage girls. I had younger men who would ask girls what size penises they were into. I had a new photo or video camera creeper trying to take covert shots of girls boobs/butts and under skirts every 15-30 mins, no joke. I had a young man with a “Free Hugs!” sign who actually stalked my employees (who said “no” repeatedly) as we were going to the dealers room, until I turned around and told him to back the f off lest I beat the crap out of him. Men who would have their hand “slip” when taking a picture with you. I had normal looking men who who suddenly say a horribly demeaning thing to me or someone else, then look to other male customers for validation and get laughs or more rude comments. And as if that were not enough, all the women would be questioned on their nerd cred, as if we would even work in those conditions if we didn’t love (respectible) nerd culture.

In all my years at cons, I’ve had exactly one woman sexually harass (actually assault) me. She was a VA guest, very drunk, and grabbed both my breasts. She “asked” if it was okay, but only after she’d done it. So yes, harassment can come from anywhere, but it has been 99% male in my experience.

And no, what you are wearing has exacly zero to do with it. It doesn’t really need to be said, but 50% or more of my crew would be in jeans and regular T-shirts and be harassed just the same as those cosplaying. Over half my time was in jeans and it seemed like the harassment went up! (Though we have a theory that I was way more intimidating in my dominatrix outfit than I was in “girl next door” clothing.)

Why are so many male members of the nerd communities like this?

@15

The sad nature of human beeings – they think they can get away with it. A lot of people do nasty things under such circumstances and the only way to deal with it is to make clear to them that they can not get away with it. Which is pretty much what articles like these are about…

Actually this is the same problem that Bigerich shows @8 – the person there wanted something and thought she could just take it no matter the cost to others because public opinion would float her through.

I also wrote a guide for Con Organizers, Guests, Staff and Volunteers to assit them with addressing harrassment before (in planning stages) and during the event itself: http://okazu.yuricon.com/2013/07/05/convention-harassment-and-what-we-can-all-do-to-help/

“We” can be even more inclusive than just every attendee or guest. ^_^

This claim that “.. . we have to focus on the needs of those who are most vulnerable first. In the greater world, straight, white cis-men have most of the social and political power to fight back against things thrown their way, unlike the rest of us.” is simply untrue. How many men get screwed six ways to Sunday because voices like yours silence them? Oh, sure, he might be barely scraping by, maybe doesn’t have a $60K education, but daaaang, he’s a white guy: so pile on! How about we just focus on fair play for everyone? On doing right by the people around us whatever our personal hangups about their sex or skincolor might be?

Carbonel @18: I don’t want to speak for Diana, here (she’s at a con, as she mentioned, and has very limited internet access through the weekend). But as a moderator, and in the interest of fairness, I think it’s a huge leap to interpret her comments in this post as an attempt to silence men, or any other group who suffer victimization, or to “pile on.” If you want to participate in this conversation, please tone down your rhetoric and make your points in a civil manner, in accordance with our Moderation Policy. This is a post about how to make fandom better, and more inclusive– no one is under attack, here. Thank you.

My sister is at a con right now, I posted one of the links to her FB account.

Carbonel @18 it is setting up a strawman argument to suggest that by concentrating on the most oppressed we must automatically oppress the less oppressed. By fighting oppression at it’s worst we can highlight what oppression is, which helps all oppressed people.

Might it be a good idea to stop throwing around the word “Nerd” so much and so proudly? I don’t love the label and i’ve noticed “Hey i’m a nerd” is a sort of catchall for a lot of people to excuse themselves for all manner of anti-social habbits. Yes I’ve heard “I’m a nerd as an excuse not to wear pants.

I’m really getting sick & tired of the attitude I see so often in the “popular culture”,that you are free to basically do anything you want to anyone just because you’ve got a camera crew following you. Being on TV gives you the right to harass people?