While some of the characters in Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar grapple with the concept of quantifying and manipulating gravity, others posit that even when understanding of the physical forces of the universe fail you, love remains greater than everything else. Anne Hathaway’s character Dr. Amelia Brand says as much, in the movie’s most polarizing speech:

Love isn’t something we invented. It’s observable, powerful, it has to mean something… Love is the one thing we’re capable of perceiving that transcends dimensions of time and space.

Various outlets are deriding Brand’s second-act exhortation as “hippy,” (sic) “goofy,” and “preposterous.” Some blame Hathaway’s delivery, while others think that making Interstellar about love just as much as it’s about time, space, and gravity was a huge misstep on the Nolans’ part.

But why do we have such an adverse reaction on the concept of love as a force in science fiction?

Spoilers for Interstellar (as well as the other books/movies discussed) are ahead.

We have no problem believing in the all-encompassing power of love in fantasy. Harry Potter was spared from an Avada Kedavra curse—and several subsequent wand matches with Voldemort—because of the love his mother Lily shielded him with upon death. This explanation doesn’t require a detailed equation or precise potion; we simply accept that love and magic are linked.

But if the Thor movies have taught us nothing else, it’s that magic and science are not mutually exclusive. Through transitive relation, why can’t love also exist on the same plane as science?

In Interstellar, Amelia Brand regards love in much the same way that we regard gravity: It’s this complex force that influences everything; we’ve measured and observed it to the point where we have a pretty clear understanding of its effects; people devote their whole lives to observing it. And yet, we have no idea why it exists.

Time for some more transitive-theory fun: One Reddit thread suggests that gravity is the fifth dimension in which they, a.k.a. we, flourish; love (which we already describe with such words as “attraction”) is gravity; if 5-D is a plane of existence where you can know everything, then love/gravity is omniscient.

Brand argues in the film that love is a propulsive force, sending us in the directions we need to go. Sometimes we feel that we are tapping into that force of love; other times, it picks us up and forcibly pushes us toward the right decision or action. This isn’t unique to Interstellar; other sci-fi works ascribe much the same power to love, including the ability to manifest as a weapon and the power to induce self-awareness and evolution.

Love as propulsive force

First, let’s get this out of the way: Christopher Nolan’s other big, mind-bendy movie Inception is also about love propelling people to achieve amazing feats. Dom Cobb’s love for his children is what drags him out of Limbo and through all of the interlocking dream layers, to finish the job and return home.

Cobb is not unlike Cooper (Matthew McConaughey), who had to jump into the black hole in order to save humanity, especially his children. No matter that our 5-D civilization planted the wormhole in the first place; without Coop’s desire to save Murph and the rest of humanity, the sequence of events would not have occurred and Earth wouldn’t have gotten saved.

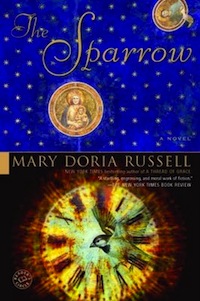

But love doesn’t push us across time and space only in the Nolans’ universe. The explorers in Mary Doria Russell’s novel The Sparrow believe themselves called by God (or some other higher power) to embark on a mission to the planet of Rakhat. At first it’s coincidence that brings these people together, with the right set of skills and knowledge, to hear an alien transmission for the first time and be called to visit this distant planet.

But love doesn’t push us across time and space only in the Nolans’ universe. The explorers in Mary Doria Russell’s novel The Sparrow believe themselves called by God (or some other higher power) to embark on a mission to the planet of Rakhat. At first it’s coincidence that brings these people together, with the right set of skills and knowledge, to hear an alien transmission for the first time and be called to visit this distant planet.

But Father Emilio Sandoz, the Jesuit priest and sole survivor of the Rakhat mission, believes that the force drawing him and the rest of the explorers to a whole new star system is God’s will. Greater than God’s will, it’s His love. Sandoz relates how, upon their precarious landing in the alien planet’s atmosphere, they all clung to love for comfort:

I am where I want to be, they each thought. I am grateful to be here. In their own ways, they all gave themselves up to God’s will and trusted that whatever happened now was meant to be. At least for the moment, they all fell in love with God.

No one is more in love with God than Sandoz, who believes that he has achieved his life’s work and that his faith is being rewarded. Hoo boy, is he wrong.

Speaking of sci-fi works that deal with humans’ thorny relationship to religion… In Joss Whedon’s Serenity, love is more vital than a spinning engine or complete mastery of the pilot’s console, as Mal explains to River on her first flight as Serenity’s new co-pilot:

You know what the first rule of flying is? Love. You can learn all the math in the ’verse, but take a boat in the air that you don’t love… she’ll shake you off, just as sure as the turnin’ of the worlds. Love keeps her in the air when she oughta fall down, tell you she’s hurting before she keels… makes her a home.

Love as a weapon

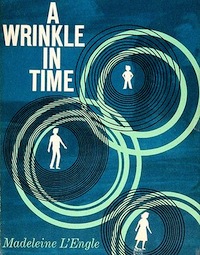

When Meg Murry must do battle with the massive creature IT to free her little brother from its grasp in Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time, she receives three gifts from her guides Mrs. Who, Mrs. Which, and Mrs. Whatsit. One quotes a Bible passage to her; another gives her love; and the third tells her that she has something that IT doesn’t have.

When Meg Murry must do battle with the massive creature IT to free her little brother from its grasp in Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time, she receives three gifts from her guides Mrs. Who, Mrs. Which, and Mrs. Whatsit. One quotes a Bible passage to her; another gives her love; and the third tells her that she has something that IT doesn’t have.

If you guessed love, then you’re catching on! By the time Meg gets to her brother Charles Wallace, he’s almost been absorbed into IT—just another identity-less minion. But by focusing her love on him, she brings out his uniqueness, something IT could never possess. Boom.

While The Sparrow was about one man’s love in God being shaken, its sequel Children of God sees a woman, forever resistant to love, harness it as a weapon for revolution. Sofia Mendes, thought slain by the end of the first book, has survived on Rakhat, pregnant with her dead husband’s child and knowing that humankind has abandoned her (as she taps into the communications between Earth and the ship, realizing that they have left for the return trip without looking for survivors). Love is a debt, she tells herself. When the bill comes, you pay in grief. Yet she has no other choice but to love the aliens among whom she makes her home and who she eventually leads to independence from their masters.

Love induces a similar cultural upheaval in Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples’ sci-fi comic book series Saga. Enemy soldiers Marko and Alana fall in love, have a baby, and try to escape the clutches of various species who want to erase all treasonous evidence of their existence. Interestingly, Alana and Marko’s attraction doesn’t start with some pure, omnipotent force; they bond over trashy romance novels with secret political messages. Still, one book is enough to spark a love that turns the galaxy upside-down.

But also, Alana has a gun called a Heartbreaker, so that’s wonderfully literal.

Love as evolution

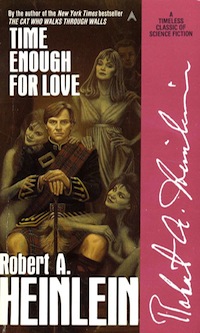

The immortal and flesh-and-blood characters in Robert A. Heinlein’s Time Enough for Love spend a lot of time debating the L-word. Some of them have all eternity to muse on its nature, while others yearn to know the answers before they pass out of this plane. But in debating computers’ self-awareness, immortal being Lazarus Long best sums it up:

The immortal and flesh-and-blood characters in Robert A. Heinlein’s Time Enough for Love spend a lot of time debating the L-word. Some of them have all eternity to muse on its nature, while others yearn to know the answers before they pass out of this plane. But in debating computers’ self-awareness, immortal being Lazarus Long best sums it up:

Babies or big computers—they become aware through being given lots of personal attention. “Love” as it’s usually called.

In a way that neither the passage of time, nor gravity, nor data can achieve, love is the key to evolution. Love lifts us up where we belong to another state.

…Perhaps to the fifth dimension? Interstellar never explains how we become they. Perhaps it’s love that ushers us into a new state of being. Perhaps our future selves are able to finally grasp the breadth of love’s influence across all of the dimensions.

Look, it was a cheesy speech designed to seed in a later plot point. I won’t deny that. But the emotional factors shouldn’t undermine the idea that love is just as concrete and powerful as the other forces making up our universe. It’s no more unstable than certain radioactive elements, it pushes and pulls us better than gravity ever could, and it endures through time.

Natalie Zutter writes plays about superheroes and sex robots, articles about celebrity conspiracy theories, and Tumblr rants about fandom. You can find her commenting on pop culture and giggling over Internet memes on Twitter.

The link between gravity and love goes back at least to Dante, who wrote about the love of the Prime Mover, God, as the “love that moves the sun and other stars”.

Similarly, Catholic theologian Peter Kreeft says:

Or to put it another way, any sufficiently advanced physics is indistinguishable from metaphysics.

My biggest problem with this that it would have been really powerful subtext, but because Christopher Nolan doesn’t deal in subtext, he literalized it in a way that was distracting for a movie otherwise filled with physics. If it had been handled with a subtler touch, I think more people would’ve gone along with it.

I didn’t mind it too much, though, perhaps because the reviews made me think it would be even more egregious. I was more willing to accept that love made him able to manipulate his own timeline than that love could send him across the galaxy to communicate with his now-grown daughter.

Science Fiction, at least the kind I grew up with, deals with, well, science. And Science is about things that can be measured, that are tangible. That’s one of things that differentiate scifi and fantasy—moving beyond the world of science (physics, chemistry, math) and into the realm of the indefinable (magic, the Force, and Love).

Love is inherently nonscientific, is not something that belongs in the realm of rationalistic analysis, and that’s why in the realm of (at least hard) SciFi it doesn’t work well. Heinlein’s later works, where he spends more time with emotions than he does with spaceships, are moer controversial, less loved (so to speak) as works of SciFi. Asimov made only one attempt to write a work that focused on emotions (The Gods Themselves) and it has always been felt to been one of his weaker works.

That’s my take, anyway, on why a squishy, inherently non-quantitative and non-measurable item such as Love has never seemed to work well in SciFi.

I loved the film and its themes, but I did look a little askance at that speech.

I don’t think anyone is taking issue with the fact that love is a powerful motivator of humans and other sentient beings. So is fear, and lust, and hunger, and curiosity, and hatred; these are powerful drives that have at least some connection to our biology and evolution, and can cause us to do things that can significantly affect our society and the environment around us.

I think the issue with Brand’s speech is that she seems to talk about love as some sort of universal constant built into the physical fabric of the cosmos, like gravity and electromagnetism — as something that exists outside of the brains and emotions and intentions of sentient beings. That’s not what Mal is saying to River; Mal’s just being poetic. He’s not saying love literally keeps the ship in the air; he’s saying you have to love your ship to be motivated to take care of it and fly it well.

That’s not a knock on love. Even Carl Sagan’s Contact acknowledges its importance: “You feel so lost, so cut off, so alone, only you’re not. See, in all our searching, the only thing we’ve found that makes the emptiness bearable is each other.” But I don’t think even Sagan claims that love is an impersonal physical force, like gravity, that binds the universe together and literally transcends space and time. We love, and so love is important to us. I don’t think the universe cares one way or the other.

Maybe I’m wrong, and maybe our 5-D future civilization will figure some stuff out about love that we haven’t. But I can see how it can seem like too much of a logical leap in the context of this film. Or maybe it’s just introduced so suddenly and awkwardly that it doesn’t feel “earned,” and seems more like an easy out: “We’ll solve this problem with love!“

I’m fine with emotional content in my SF but at the end of the love isn’t a physical force like gravity, it’s a biochemical action with societal interpretation. It’s doesn’t make heavenly bodies orbit around each other. Love is a personal finite thing, gravity, at least in so far that this universe is concerned, is forever.

@5 exactly. Tom Riddle spent all his time in Dark Arts and skipped out on physics.

“There is a power that you have and Voldemort doesn’t, Harry; it’s called gravity.”

@6 it should have gravity, or like a missile launcher or some such thing.

Another work where love plays a fairly important part as a physical force would be Dan Simmons’ Endymion – but honestly, I think introducing that was when the whole Hyperion Cantos started to go sideways.

As to why “love as a force” works just fine in fantasy, but is a real hassle in science fiction – I think Bill had a very good explanation over in the Malazan reread: fantasy allows for the metaphorical to become literal; science fiction at most allows for a fictional set of rules for its physics – if you’re not able to (somewhat) specify those rules, it breaks down really fast.

@Dr. Thanatos: It’s interesting that you consider The Gods Themselves as one of Asimov’s weaker works when it won both the Hugo and Nebula for best novel. It must really have been a sucky year.

Let’s look at the competition:

The Book of Skulls

Dying Inside

The Iron Dream

The Sheep Look Up

What Entropy Means to Me

When HARLIE Was One

There Will Be Time

A Choice of Gods

@BDG

You made me flash back on an old comedy sketch I heard at a convention about thirty years ago about the selling of Star Wars.

Lucas: And there’s this Force. It runs throughout the universe. It’s in everything. It binds the universe together.

Studio Exec: George, that’s gravity.

I probably didn’t remember it exactly, but it has spoiled a certain scene in a certain movie for me forever. Much as Big Bang Theory has ruined the first Indiana Jones movie.

@focoulter,

It was a sucky year. I read it the year it came out and the buzz in the magazines (there were no blogs or instant feedback then) was that it was one of his weaker efforts and a demonstration of why his more popular novels avoided discussion of interpersonal relationships.

Also a demonstration of what we all know from other venues: winning awards doesn’t always imply quality…

Of the nominees I’m familiar with, I think Dying Inside was probably more worthy of a win… I suspect the other nominees may have also felt victim to the thinking: “What? Asimov hasn’t won a Best Novel Award yet? ASIMOV? Also this has been his first novel in a while and for all we know, it might be his last ever… and he’s clearly stretching himself better do it now!”

If love is a physical force in the Universe, I’m gonna write me some starships powered by Carebears in my next story…

“Scotty, we need more power!”

“Aye, Capt’n, let me throw a few more of these buggers into the warp core!”

You had me until “trashy romance novels.” Way to insult another genre and all its readers.

If a reader wants fiction about people surrounded by science, then love and other emotions are just fine and absolutely necessary to make a story live.

If the reader wants fiction about science without emotions, then love and other icky things aren’t wanted. (But why isn’t this reader reading nonfiction instead of complaining?)

Also, frankly, some people haven’t a clue about emotions like love so writers might as well be writing gibberish as far as they are concerned, and these people complain. And again, why aren’t they reading nonfiction and the Discovery Channel instead of complianing about what the rest of us “get.”

@14 I’m not opposed to emotional content in my science fiction, in fact I quiet enjoy and often find that without stories end up being dry made-up science deliveries devices. That being said I’m not a fan of making a human emotion, a thing apart of our biology and socities a universal force upon the universe. It’s a blindingly anthrocentric way to view in my opinion. Love might be a very strong motivation for us but I highly doubt it’s one of the fundamental forces of the universe.

There’s nothing wrong with the concept itself. The problem is the unsubtle way it was handled. Nolan’s scientists ramble about love like a drunk cattle auctioner on the autism spectrum. Emotions need to be shown through the characters, not told by them. Love needs to be implied, not explained like quantum mechanics.

Or else your audience is probably going to laugh at you.

I didn’t know this was a big issue–while watching the movie I thought her speech came a little out of left field but I let it pass.

I think @2 has it right, that it just wasn’t handled well. I could see this movie where the subtext was there the whole time and it would have made this bit about love fit perfectly. But there was no subtext, no subtlety, so it made this speech seem really awkward. Also, I think it might have been better coming from Cooper than Brand (were the subtext done correctly).

Overall it just played off like a Big Lipped Aligator Moment.

@12: I see _The Book of Skulls_ was there too, also by Silverberg. Maybe the vote got split.

I think Nolan’s writing is at its best when he’s sort of tackling emotions from the side rather than head-on, but I’ve been wondering where the scoffing and eye-rolling has been coming from on this one as well.

What bothered me more about the movie is the notion that the fifth-dimensional beings are humans from the future, which I thought was a conclusion Cooper came to without much, if any, reason to, and which seemed to go against the entire spirit of the movie. I think the better answer to “Why did they bring us here?” would have been “I have no idea, let’s get out there into our new galaxy and find out.” Not everything needs to be tied up neatly, and aliens are perfectly all right to have in science fiction.

“But if the Thor movies have taught us nothing else…”

wtf?

@MByerly I don’t think “trashy romance novels” in this context is meant as a slam against the genre as a whole. In Saga, everyone from the ficticious author on down is really clear that the novels in question are pretty trashy but also oddly compelling and stealthily subversive. I’ve not seen any comments from the author of Saga, though, so I can’t comment on how he feels about the entirety of real world romance novels.

I’m not a scientist. I’m an artist. It seems to me that there are many mysteries in this world that are most likely measurable, yet we do not know how to measure them at this point, or perhaps never. So if love is a true thing that occurs, then I’d like to think that it is quantifiable. If we could measure love, hate, fear etc, .and if we could understand the profound affects that it has on the material world then the question about the meaning of life would be answered. I think humanity would be far better off recognizing that our feelings directly influence many aspects of science, whether it be our health on a cellular level, or the way we treat our earth.

I liked the movie and the parallels between love and physics. It is afterall a movie about saving humanity and it does not take a physicist to know that you could have all the scientific knowledge in the world, but it wouldn’t mean a thing if we didn’t have feelings to propel us–one can not exist without the other. Every part of life, whether it is gravity, love, a microscopic organism, an element,etc… we need it all for survival and it is all related.

“darkness does not exist, darkness is simply a product of the absence of light.”

We claim darkness does not exist, but that is only because we cannot logically prove that it does. Yet it surrounds our every space once the light is absent? How can it be that something that occupies so much space be nonexistent. You see I believe that logic is a product of mans own understanding of their environment. Logic is Sort of like saying that that in order for the lock to work you must first have the key also. Believing in logic only, is similar to only believing in half of the moon, only because at that time you can only see that half. At this time, logic may be the more firm and safe option but I know that the things which are unseen are more real then those which can be seen. We are a product of our own understanding….

Hey, thanks for the shout-out.

I wouldn’t say I disagree about the role of love and emotion in sci-fi and fantasy; I just don’t think this movie sold either of the underlying relationships (Murph/Cooper or Brand/Edmund) enough for this speech to make any kind of sense. And given that it comes out of nowhere for the character, it just feels like a sloppy undermining of Hathaway’s character to create drama that’s neither justifiable in the script, nor particularly consequential. The only consequence was a disaster that was a direct result of their refusal to go along with her preferred choice, but this was not something they could have predicted, nor does it make Brand correct to have chosen this planet for personal reasons.

There is a very similar debate in the movie Sunshine (spoilers coming) in which the characters debate the potential merits of trying to rescue a spacecraft from a prior mission. The stakes are identical in both films – they’re trying to save the entire human race. And in Sunshine, the discussion proceeds very differently – they acknowledge that even if they knew for sure that the previous crew were still alive, diverging from their mission in the interests of rescuing them is not even a remote possibility. All of them are expendable – full stop. When they decide to go after the other spacecraft nonetheless, it’s for reasons that are justifiable within the context of their mission (second nuclear payload = two chances to succeed in their mission). It’s the correct decision, even if the results of that decision end up being disastrous.

And that’s the key difference here. Cooper and Brand bringing up her prior relationship with Edmund undermined her credibility because it was the first thing that came up, and it was irrelevant to the decision of which planet to go to. Brand even attempted to acknowledge this after her love-speech, and Cooper (rightfully) shut her down.

If they had done more to establish her prior relationship with Edmund (or even shown Edmund on-screen), I may have felt differently about the emotional/dramatic content of the scene, but in terms of depicting this as a critical decision by a team of world-saving astronauts, I can’t imagine a version of this scene in which they come away looking like professionals.

Awesome stuff from Nolan, however these plot holes are hard to ignore:

http://digestivepyrotechnics.blogspot.com/2014/11/interstellar-plot-holes-explained.html

Was I the only one that viewed the speech by Brand as an attempt by her to convince the other two to go to her boyfriends planet instead of the other one? I read it more as “I have no scientific reason to go there, but I need to try to convince you anyway because I want to save the guy I love.”

Love is a powerful and essential force in the arena of human relations. But it dwindles to utter irrelevance in terms of the universe as a whole, just as we do. These attempts to portray love as a universal force merely reflect the underlying narcissism of those making the suggestion. The Earth is not the center of the universe, and love is not a fundamental quality.

We live in a universe that is incapable of caring about us. If that makes you all depressed, too bad, but that will be a reaction founded on laziness. We are the only ones who can create a caring and loving environment. It’s a hard and difficult task, but it can be done as long as we realise that we are the ones who need to put in the work, and we’ll get nowhere waiting for some vague imaginary force to do it for us.

Very little Science Fiction is actually about science. Mostly it’s about people, like all fiction. So of course love has a part to play, and it’s a very important one. But let’s never get the delusion that it isn’t just something we’ve invented to make ourselves feel better.

Maybe this could help….

http://moviepilot.com/posts/2014/11/22/got-5-minutes-all-your-interstellar-doubts-explained-here-huge-spoilers-2453531?lt_source=external,manual

@27 I do like that last sentence, it really is as fine and to-the-point a comment on religion I have ever seen – not so much about love though. Love may be a self-delusion, especially the romantic version beloved of Hollywood, but the love of a parent for his/her children at least has some basis in physical evolutionary terms – witness the defence of off-spring across most animal species.

@@@@@ 22 K. Wilson: Very well put! You saved me some typing (and I’m a scientist)

@@@@@ 27 Charleski: Love isn’t something we’ve invented; it’s the (basically inescapable) net effect of all the stimuli, responses, memories and thoughts connected with the things we have chosen to feel positively about. And often you don’t have a choice at all. e.g. baby pandas.

So, no, not a universal force, but as far as intelligent life is concerned, central and pivotal.

I’ve been thinking a lot about ways to improve Interstellar’s ‘second act,’ and one would be to have Romilly give the ‘love’ speech instead. He had, after all, just spent the better part of 23 years mulling over everything his brain could think of. So in this scenario, Brand starts off saying ‘we need to go to Edmund’s planet,’ then Cooper says ‘it’s only because you love him’ – and then Romilly says, ‘well, I think love is the one thing etc. etc.’

This would have taken the words out of the mouth of the one female astronaut (strange how we’re no longer allowed to have females talk about love) and put it in the mouth of the one person who would have some really wild ideas about everything at that point.

ALSO, this would force Cooper to disregard the love theory out of something other than contempt for Dr. Brand wanting to see her boyfriend again. And later in the movie (the Dr. Mann part, which I am also hard at work fixing), when Cooper realizes both Romilly and Brand were right and they should have gone to Edmund’s planet and now he’ll never see his children again, it would have a huge emotional impact.

SCENE FIXED. :-D

“In Interstellar, Amelia Brand regards love in much the same way that we regard gravity: It’s this complex force that influences everything; we’ve measured and observed it to the point where we have a pretty clear understanding of its effects; people devote their whole lives to observing it. And yet, we have no idea why it exists.”

I think this is a good pointer to the main reason “Why … We Reject Love as a Powerful Force in Interstellar?”.

We have a pretty reasonable idea why it exists and what it is. We don’t need to add pseudo-scientific dimentionality or force attributes to it in such a literal way as Interstellar tries to.

The biological, evolutionary and social sciences would give us a fairly well rounded picture of the electrochemical interactions going on and the reasons why it is advantageous to us as an organism.

Sorry if im regurgitating what’s already been said – either in the blog or comments. There is too much to read – though i did skim it.

The “love logic” is one of the most interesting themes in intersteller. It can be viewed in a purely scientific way:

We love those for (amongst other things) their trustworthiness – we are more likely to love someone who is trustworthy, than someone who is not trustworthy.

Amelia loves Edmunds – so this verifies his trustworthy nature. We do not have such verfiying data for Mann (as far as we are aware no one loves him). (Secondly Ameilia knows both men but chose to love Edmunds rather than Mann)

Therefore we have more data that Edmunds is trustworthy and that his data is trustworthy, compared to Mann.

Therefore Edmunds planet is the correct choice. It is right that “even though we don’t understand why” love is leading us to a scientifically better choice.

On an issue not related to love – i also really like Amelias observation that the near the planet is to the black hole the less chance there is for life to occur.

Love is the one force that drives mankind to acheive his true greatness. In fact, one could argue the God created the Cosmos because of love.

The message of the movie is to always follow your heart– something that Hathaway speech (while good) fails to deliver, even if the scipt tried to. Had the scientists followed it, they would have arrived safely on Edmunds planet and possibly been spared all of the tragendies they eventually overcome. They chose to follow science, and look what happened.

Elder Brand, Mann and others were betrayed by their minds but in the end Hathway’s character is the one that survives as does Cooper and its love that drives him to finally go rescue Brand from an eternity of lonliness.

To that I toast the writer of this script, because it is the failing of so many today to betray their hearts for their minds to the detriment of all.

” Love isn’t something we invented. It’s observable, powerful, it has to mean something… Love is the one thing we’re capable of perceiving that transcends dimensions of time and space. ”

“Love, and do what you will. If you keep silence, do it out of love. If you cry out, do it out of love. If you refrain from punishing, do it out of love.” ? Augustine of Hippo

Remember:

The Black Hole was called: Gargantua;

And the Neutron Star: Pantagruel;

This is a clear reference to the philosophy of Thelema:

“So it was that ?#?Gargantua? had established it. In their rules there was only one clause:

DO WHAT YOU WILL!

because people who are free, well-born, well-bred, and easy in honest company have a natural spur and instinct which drives them to virtuous deeds and deflects them from vice; and this they called honour.”

http://historyguide.org/intellect/rabelais.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gargantua_and_Pantagruel#Gargantua

To understand how “Love” could function as a driving force for evolution in a multidimensional context, I recommend Rob Bryanton’s Blog:

http://imaginingthetenthdimension.blogspot.de/2010/07/love-and-gravity.html

I think Nolan was trying to say something by implying that love is a tangible force that transcends time and space.

I think he was trying to make a point about how love is the only thing that can save us from ourselves.

The film was set in a realistic near-future… in a setting that is plausible in the real world. It’s a world driven by selfishness, much like our own, and it’s a world that’s going to end because of it.

Cooper’s son lets his love for his father die out, and then becomes fuelled by hatred, and we see the effect it has on himself and his family.

Murph’s love for her father never dies out, though. Her love for her father brings her back to her home and allows her to find the watch that saves humanity.

Cooper’s love for his daughter almost ‘forces’ him into the black hole, where he’s able to transmit the vital information to Murph that will save the world.

The mutual love that Murph has for Cooper and vice versa is what saves humanity.

Brand makes a pleading speech about love, and that her love for whoever’s on that planet has meaning… and what ensues when Cooper doesn’t agree is disaster. Moreover, who they find on the cold, barren planet is someone inflamed by selfish desire. His love for himself overrides his love for humanity and he almost ends humanity because of it.

Cooper later on willingly ‘sacrifices’ himself for the sake of humanity. His love for humanity and, mainly, Murph is what pushes him into the black hole.

The idea that Love is this tangible force that can transcend time and space was just an analogy…

Throughout the movie, there is this battle between love and hatred, selflessness and selfishness, and how every act incited by hatred and selfishness leads humanity that closer to extinction, while every act incited by love and selflessness brings humanity closer to salvation.

Nolan was trying to make a point about how Love is the only thing that can save us and this world.

Just came across this thread as I have recently come to the belief, after much thinking, reading and life experiences, that love is a fundamental force of the/this Universe, like gravity. So I started looking for information that expands on this idea and found this thread, among many others. Thank you to the writer of this article and to all the commenters! Your ideas are marvelous and well-articulated, and have really been eye-opening. Even the ones that disagree with the idea of love as a physical force. Liked esp. one of the comments that said (paraphrased) ” Advanced physics becomes metaphysics.” And just read the embedded link in one of the comments to this blog:

http://imaginingthetenthdimension.blogspot.de/2010/07/love-and-gravity.html, wherein the writer links so-called “New Age” ideas that sound cheesy to actual science-based phenomenon. Excellent. Here is a link to a blog about similar thinking found in the ancient Vedas: https://bhavanajagat.com/2016/05/03/love-defined-as-fundamental-force/

Throughout the article and the comments, I found a consistent reference to human parental love as a prime motivator and necessary to our contd. existence, including how in non-human species, the drive to protect offspring is instinctual and intense. I believe that this form of human love is one of the most powerful because it is not necessarily always reciprocated (as in romantic love), and yet, it continues.