Welcome to the Disney Read-Watch, in which we’ll be reading the texts that inspired classic Disney films, then watching the films. Today we’re starting with the prose story of Disney’s very first feature-length film: Snow White, by the Brothers Grimm.

You know the story, right? Girl flees evil stepmother for a life of unending housework with seven little men before falling over from an overconsumption of apples and placed in a coffin until finally a prince swings by to rescue her from all this crap.

Or do you?

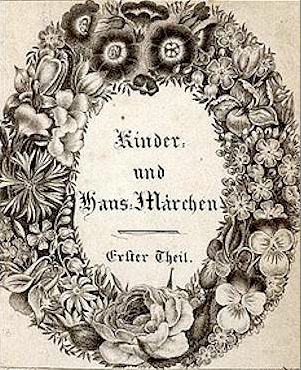

The story Walt Disney worked from was the version published by the Grimms in their second edition of Children’s and Household Tales (1812), later collected by Andrew Lang in The Red Fairy Book (1890) as “Snowdrop.”

Sidenote: this wasn’t a deliberate attempt to be confusing. Lang partly needed to distinguish the story from the other Snow White—the girl in “Snow White and Rose Red,” a story collected in his earlier The Blue Fairy Book, and partly wanted to make a nod to the fact that the two Snow Whites have slightly different names in the original German, something the different translations for the names reflect. Later collections, however, ignored Lang and returned to “Snow White,” causing some confusion afterwards.

The other Snow White, by the way, also runs into problems with a dwarf and ends up marrying a bear. It’s an amazingly bizarre little story where absolutely no one’s actions make a lot of sense and where characters randomly pop up and equally randomly vanish—but it’s also a lovely example in fairy tales of two sisters who work together and get along. Recommended for a short read.

Anyway, both the Grimms and The Red Fairy Book helped popularize Snow White for an English reading audience. The story, however, was well known in Germany and Italy well before the Grimms collected it. Just in rather different versions. In some retellings, for instance, Snow White is the youngest of three sisters; in another version, the Mirror is a small magical dog. In at least one version of the tale, Snow White does not seem to be a real human girl at all, but rather a magical construct created by flinging drops of blood around in the presence of ravens. And in many versions, Snow White is aided not by dwarves, but by robbers. Sometimes she does housework. Sometimes she doesn’t.

And in the first edition of Children and Household Tales (1812), carefully tidied up for a literary audience, the evil queen is not her stepmother, but her mother, in an echo of many Italian versions of the tale.

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm had excellent reasons for changing that little detail in second and later editions of Household Tales: several critics felt that the stories in the first edition, including “Snow White,” were entirely unsuitable for children, though children, as obedient then as now, read the book anyway. (I’m in no position to judge.) Thus, pregnancies were hastily removed; the violence was (somewhat) toned down; mothers turned into stepmothers; moral lessons were added everywhere (including, as here, the value of obedience and housework in women). Not everything got changed—as we’ll see, when we get to “Cinderella” and Disney’s decision to work from the French version of that story instead. But quite a bit.

Even with those changes, “Snow White” remains grim in the truest sense of this word.

The story starts off talking about drops of blood, and things just get worse from there. By the end of it, we have attempted assassinations, attempted cannibalism, the tragic death of an otherwise innocent boar (lesson learned, wild animals in fairy tales: learn to talk before you get treated as replacements for human flesh), poisoning, torture, and, oh yes, more than a touch of pedophilia. And no, here I am not talking about the dwarfs or the questionable household arrangements of seven short men and the girl they’ve forced to do housework for them, although I am reliably informed that the internet contains a lot of unsafe for work speculation about that. It’s a brutal story, is what I’m saying.

The Grimm version is not exactly subtle in other ways: the dwarfs only agree to protect Snow White after she agrees to do housework for them. This, even though when Snow White finds their house, it’s described as neat and clean, a detail later changed by Disney. (Indeed, Disney takes the entire housework thing a step further, but we’ll get to that.) As long as Snow White stays focused on doing housework for the dwarfs, locked in their house, she remains safe. The trouble comes when she gets distracted from that job by the arrival of a distraction—a woman. Abandoning her proper place leads to death. Three times, just in case you didn’t get the message.

The first two “deaths” are brought about by objects associated with improving a woman’s appearance/sexual attraction: a corset, laced too tightly (something that actually did cause women to get short of breath in the 19th century), and a comb, poisoned. Trying to become beautiful might kill you; do housework and you’ll live. Got it. That message is then again undercut by the ending of the tale, where Snow White is saved because the prince falls in love with her beauty, but the idea of hard work = good; modesty = good; focus on personal appearance = bad, still stays strong.

Speaking of that prince, however:

The Grimm and the Andrew Lang versions very explicitly, and unusually for a fairy tale, give Snow White’s age. She is, they explain, seven when she was “as beautiful as the light of day,” (the D.L. Ashliman translation) or “as beautiful as she could be” (Margaret Hunt/Andrew Lang translation). At that point, the mirror starts delivering some hard truths and Snow White gets escorted out of the woods to die. When that fails, the queen starts trying to kill Snow White before finally succeeding. Snow White’s responses to these attempts are extremely childish—which, given the age mentioned in the story, makes complete sense. It’s very safe to say that Snow White is no more than ten years old when she is placed in the coffin, at which point, again to quote Grimm and Lang, we are told that she does not decay and looks exactly the same. In other words, she doesn’t age.

Which makes her still about ten when the prince finds her and the coffin in the woods.

If that.

So, to sum up: This makes our prince one creepy guy. Not only does he have a weird fetish for red hot iron shoes and making people dance in them at his wedding (like, think of what that sort of entertainment could do to your floor, dude. Think of what your craftspeople are going to have to do to fix it) but his idea of romance seems to go something like this:

Prince: OOOH! Ten year old dead girl in a coffin! I WANT THAT.

Dwarfs: Er…

Prince: I NEED TO HIT THAT.

Dwarfs: Er….

Prince: I will cherish and love it as my dearest possession.

Dwarfs: It?

Prince: I’m objectifying!

Dwarfs: Well. Ok then!

I’m thoroughly creeped out, is what I’m saying here.

And I think I’m expected to be. This is, after all, a story about beauty and vanity and its dangers, and as the final sentences, with their focus on red hot shoes and torture show, it is meant to have more than a touch of horror about it, a none too subtle warning of what might happen to women who allow themselves to be distracted. It’s also a meditation on the age old proverb: be careful of what you wish for. The story starts off, after all, with a queen’s wish for a child. And a warning about the dangers of beauty. It’s strongly implied that had Snow White been less beautiful, that she might—she might—have been able to grow up in obscurity. And what made her so beautiful? Her mother’s wish, made in blood.

And yes, I’m pretty sure that she really is meant to be seven, or at least no more than ten, in the tale: this is a young girl who constantly opens the door to strangers, even after getting killed, even after being told not to, by adults. And it is that disobedience, and that trust, that end up getting her killed—even if only temporarily—and handed over to a stranger. It is that disobedience and that trust that ends up getting her stepmother killed. (Not that we’re meant to feel particularly bad about this.) The Grimms, and the people who told tales to them, knew about trust and disobedience and failing to protect loved ones, and they worked it into their tale.

It takes an active imagination to make any of this cute. Walt Disney and his animators had that imagination. Not that they quite left out the horror, either, as we’ll be seeing soon.

Mari Ness has previously wondered about that glass coffin. She lives in central Florida.