There’s a lot of magic in Shakespeare: ghosts in Julius Caesar and Hamlet, witches in Macbeth, elemental spirits and wizards in The Tempest, and fairies in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, just to name some obvious ones. But the magic of The Winter’s Tale—if it even is magic—is of a whole different variety.

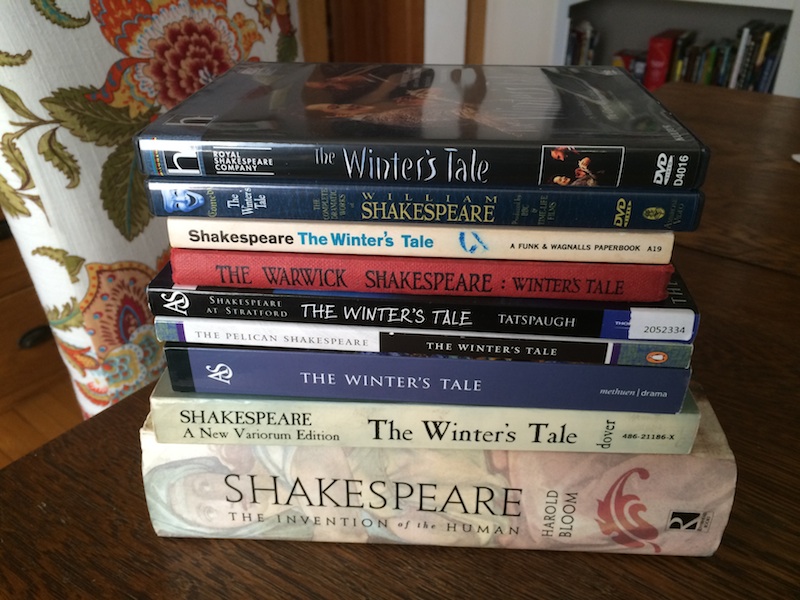

When I began writing my novel He Drank, and Saw the Spider, my initial spark of an idea was to drop my hero, Eddie LaCrosse, in place of Autolycus in The Winter’s Tale. The mystery (the LaCrosse novels are all mysteries) would center around the nature of the oddly regal young shepherd’s daughter.

What I discovered as I re-read the play was that any production (or, in the case of my novel, any adaptation) of this play has to make some serious decisions about just what the hell happens in it. This is no simple love story, or revenge tale. This one is just plain nuts.

For those who haven’t read or seen it (it’s infrequently performed, for reasons that will become clear), the plot begins in Sicilia. King Leontes is convinced that his wife, Hermione, is cheating with his best friend Polixines, the king of Bohemia. Polixenes flees for home, and Leontes puts the very pregnant Hermione on trial. Despite no evidence, and with even the testimony of the Oracle at Delphi telling him he’s wrong, Leontes convicts her. She gives birth in prison, and Leontes orders his newborn daughter abandoned in the woods, so she’ll die without him actually killing her. Yet when the queen also dies, along with his son and heir, Leontes snaps out of his jealous rage, suddenly filled with regret at what he’s done.

And then… gear shift! It’s sixteen years later! A bunch of country folk in Bohemia are having a sheep-shearing festival. (Which includes a guy selling dildos. Yes, those sorts of dildos.) The abandoned baby girl has been raised by a rich sheep farmer and has fallen in love with King Polixines’ son, Florizel (who, despite that goofy-ass name, is a truly good, stand-up guy). In Shakespeare’s longest single scene (it runs about 45 minutes in performance), everything is set for the unwitting princess to return to Sicilia and confront the still-mourning King Leontes, her father.

Got all that?

The first three acts are full-bore Shakespearean tragedy, with dead children, a dead queen, an unrelenting villain (who ultimately totally repents), and that famous stage direction, “Exit, pursued by a bear.” Who eats the guy, by the way. And then, wham, we’re in A Midsummer Night’s Dream “rude mechanicals” territory, with goofy yokels and a repurposed Falstaffian royal-attendant-turned-thief who’s suddenly our main character.

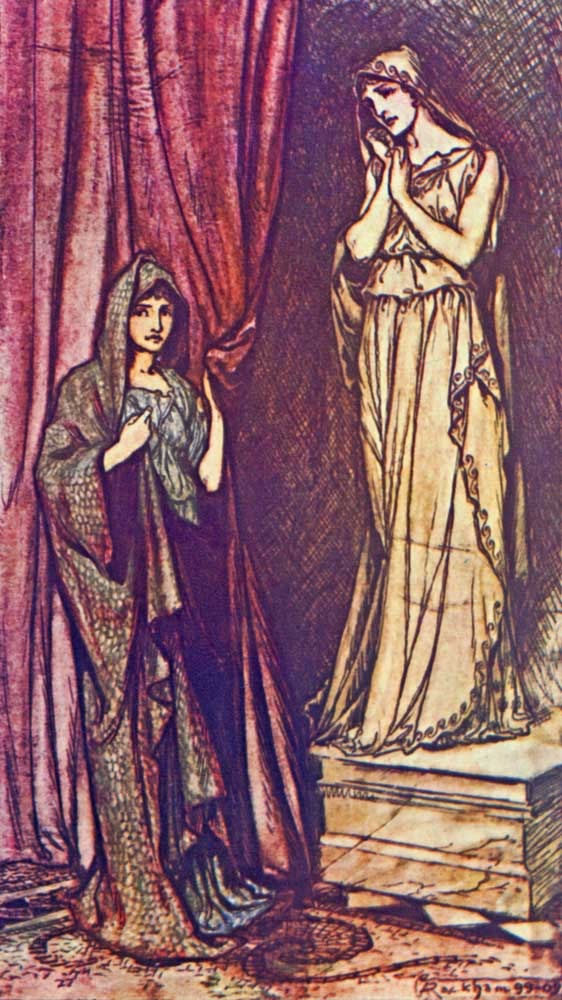

And it gets weirder. At the end, Paulina, once the queen’s handmaiden, reveals that she’s commissioned a statue of the queen. Only this “statue” has been carved to resemble what the queen would look like now, if she hadn’t died sixteen years ago. And then the statue comes to life, and Leontes is reunited with both his wife and daughter (no reprieve for his dead son, though). It’s a happy ending… right?

And it gets weirder. At the end, Paulina, once the queen’s handmaiden, reveals that she’s commissioned a statue of the queen. Only this “statue” has been carved to resemble what the queen would look like now, if she hadn’t died sixteen years ago. And then the statue comes to life, and Leontes is reunited with both his wife and daughter (no reprieve for his dead son, though). It’s a happy ending… right?

When considering a production of this play, you have to decide: Does the statue really come to life? Or is it all an elaborate trick played by Paulina and the queen, who never really died but has been hiding out for sixteen years?

There’s no obvious answer. It’s not like either option makes any real sense. But the whole play hinges on this choice, more so than even deciding whether or not Hamlet is really mad.

I’ve seen two productions of this play (three, if you count the rather excellent claymation abridgment from the BBC). I’ve read about several others. I even went so far as to contact theatrical directors and actors who had done productions and asked them what they thought. There’s no consensus; it’s such a non-sequitor moment that, no matter how you play it, it never quite fits. If it’s magic, then it’s the only magic in the show, unless you count the entirely unrelated (and offstage) Delphic Oracle. If it’s not, then you’re left with characters behaving in a way that, quite frankly, makes no sense, either in Elizabethan drama or the real world.

And that’s the glorious insanity that makes The Winter’s Tale so fascinating. It never quite comes together, and yet there’s always the sense that, if you just stare at it a little longer, read it one more time, you’ll find that missing key. It’s considered a “problem” play, and if so, it’s a problem like pi: We know it’s there, we know it works, but we can never quite get to the end of it so we can comprehend it all.

Perhaps that, then, is its greatest magic.

Alex Bledsoe is author of the Eddie LaCrosse novels (The Sword-Edged Blonde, Burn Me Deadly, Dark Jenny, Wake of the Bloody Angel, and He Drank, and Saw the Spider), the novels of the Memphis vampires (Blood Groove and The Girls with Games of Blood) and the Tufa novels (The Hum and the Shiver and Wisp of a Thing).

Great piece on a play that I’d only vaguely heard about in the past. Now I’m very interested in finding a way to see it myself. It sounds like one heck of a twisted experience and I love those sorts of experience (to an extent).

She so reminded me of my wife, you see.

This much is central to understanding.

While I was pleased to visit with my dear friend Leontes, and for so long, I was far from home, and with my own wife only recently departed, and Florizel still home in Bohemia, her brilliance was a source of peace for me.

I swear, though, that I never touched her.

But I did love her. It was my foolishness which caused her to be imprisoned by my old – now mad – friend. There was no magic in that statue save that we were all fools.

Paulina was a canny woman, you must know. She understood full-well that her own life would be forfeit if it were discovered that she had disobeyed Leontes for sixteen years. Leontes knew this also. Camillo and I could only watch, and play along.

So if the audience is left to wonder at what we had done, more’s the better. Leontes need never pardon Paulina if he pretends she’s done nothing wrong. When would a king pardon a handmaiden? Another king, surely. His own queen, certainly.

And in so doing, he gains an heir. He hay have been mad once upon a time, but the man’s no fool.

The bear, you ask?

We train those.

I’d never liked Antigonus.

“Rarely performed” may depend on your available theatrical options. I’ve seen several excellent productions…but I have the distinct advantage of having the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in my metaphorical back yard. It will be back again next season, in 2016, in the Elizabethan-style outdoor theatre. And indeed, Winter’s Tale comes around much more often in the OSF rotation than the really rare shows — Timon of Athens, King John, Titus Andronicus. (Although we are getting Timon in 2016 as well, as OSF is presently on one of its occasional let’s-complete-the-entire-canon-again runs.)

In any case, Winter’s Tale remains one of my favorite shows — whether despite or because of the ambiguity and paradox, I’m not sure. But it is definitely a very odd play.

Winter’s Tale is actually my favorite Shakespeare play. It takes us through all the pain of the tragedies and then turns us around and says that redemption and forgiveness are possible. We can see the world fall apart and we can see it heal and come back together.

The big tragedies came along after Shakespeeare’s only son, Hamnet, had died. Cue Hamlet and its speeches on grief and death and loss.

Winter’s Tale is what comes after. It’s about a father who refuses to see how he is destroying his own world. He destroys his relationship with his wife with his jealousy and false accusations. His son literally dies because of this destroyed relationship. He believes it’s also too late to fix things with his daughter.

But, he still changes. He still tries to be a better man. When his daughter and Florizel reach his kingdom, she reminds him painfully of his dead wife. This moves him to try and help the young lovers find a happier ending than his dead queen had.

This, by the way, is a frequent theme in the later plays, the father finding his lost daughter and/or helping her find her rightful place as his heir. These were plays written by a man who had lost his only son in a time when that meant much more than it does in our time. Shakespeare had earned the status of a gentleman and a family coat-or-arms only to lose the only person those could be handed on to. Yet, these later plays show a man waking up to the value of his daughters and the realization that he had undervalued them.

It’s after the king unknowingly aids his daughter and the son of the man who he had falsely accused that he at last achieves foregiveness. The question about Hermione is whether this is a miracle–whether the gods have forgiven him and restored the dead to life–or whether it is a human agency, whether Hermione has forgiven her husband and trusts him enough to let him know she lived. The question is which kind of forgiveness do you think is more important in this play?

By the way, the play also shows different reactions to a tyrant. Paulina simply refuses to back down. Hermione can do little accept plead her innocence and beg the king to remember who he once was and how he felt towards her. Another servant of the king, ordered to murder an innocent man, chooses to warn him and flee the country instead.

Antigonus knows it’s wrong to leave babies to die. He originally doesn’t believe what the king says about Hermione. But, in the end, he accepts the king’s belief and leaves the baby on an isolated shore frequented by large carnivores where he could not have expected her to survive. His actions bring down the wrath of heaven, and he himself is devored by one of the wild beasts he might have expected to eat the baby. Divine retribution is definitely something the play treats seriously.

“They crossed the broad Atlantic in the brave Florizel,

And on the sands of Suvla, they entered into Hell,

And on those bloody beaches, the first of them fell…

Enlist, ye Newfoundlanders, and come follow me!”

My favorite play of Shakespeare’s. I’ve seen it performedfour times.