Grady Hendrix, author of Horrorstör, and Will Errickson of Too Much Horror Fiction are digging deep inside the Jack o’Lantern of Literature to discover the best (and worst) horror paperbacks. Are you strong enough to read THE BLOODY BOOKS OF HALLOWEEN???

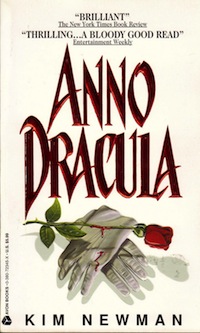

So now it’s Halloween and you want one read, one that’s scary and smart, entertainingly macabre, a book you simply have to recommend to friends, one in the great tradition of classic horror. And I have just the book for you: Anno Dracula.

Kim Newman’s 1992 novel is one of the most accomplished and thoroughly enjoyable books I’ve read in recent years. It’s big, bold, brazen, showcasing Newman’s prodigious knowledge not only of Draculean lore and legend, but also of 19th century London, Jack the Ripper, Holmesian detection, and British literature both classic and vampiric. With the kind of breathtaking effortlessness that instills burning jealousy in horror-writer hearts everywhere, Newman weaves together the twin nightmare mythologies of real-life monsters Vlad Tepes and Jack the Ripper into a sumptuous whole. “What if Dracula had won?” Newman has posited, and what a cracking yarn that question inspires, a dense yet deftly written 400-page novel in which readers can lose themselves completely.

Newman’s Vlad Tepes is also Bram Stoker’s literary creation Count Dracula, and it is this towering king vampire who is triumphant over Abraham Van Helsing, Jonathan Harker and the other men who’d banded together to stop him. Dracula’s victory occurs before the novel begins, but Dr. Jack Seward (he ran a madhouse and studied Renfield, remember) recounts the tragic backstory in his diaries early on: “We were defeated utterly. The whole country lay before Count Dracula, ripe for the bleeding.” Dracula, still the military strategist, makes his way to Buckingham Palace and makes Queen Victoria his bride, and then turns her into one of his unholy concubines. Van Helsing is recast as a traitor to the British Empire, his head placed upon a pike.

Dracula, who had been King of the Vampires long before he was ruler of Great Britain… the undead had been an invisible kingdom for thousands of years; the Prince Consort had, at a stroke, wiped clean that slate, lording over warm [the living] and vampire alike.

And now it is the year and age of our Lord and our Savior, the mighty Prince Vlad Dracula, and every knee shall bend, every tongue shall… well, not confess, exactly, but you know what I mean.

From here he turns the country into a new police state; the reign of Dracula is powered by the Carpathian Guard, brutal old-world vampires he has brought to England for the purpose of spreading vampirism and stamping out any political insurrections. Criminals and traitors and others—living or undead—who try to defy the edicts of the “Prince Consort” are, of course, summarily impaled. Newman relishes this and spares no detail. Unpleasant indeed, particularly for those who get not the pointed spike, but the, uh, rounded blunt spike. Hey-oh!

As the novel begins, vampire prostitutes are being murdered on the foggy midnight streets of Whitechapel by a killer at first dubbed the “Silver Knife,” alluding to his weapon of choice, since only pure silver can truly kill these nosferatu newborns. In this bloodthirsty new world, many living want to become immortal undead—it’s seen as a step up in society—while vampires can live quite well on small amounts of blood that humans (known as “cattle”) willingly give up. Vampire whores offer sex in exchange for a, ahem, midnight snack. And as one might expect, though, outraged Christian anti-vampire groups have formed, and England faces turmoil and riot in these days of class struggles and uncertain future. Newman has some fun with this bit of social and political satire that flows naturally from the events at hand.

Part of the fun of reading Anno Dracula is recognizing the literary and cinematic characters that Newman often wittily references and employs. Famous Victorian characters from Arthur Conan Doyle, Dickens, Wells, Stevenson, Le Fanu, and others appear (much as in Alan Moore’s later League of Extraordinary Gentlemen graphic novels). Lord Ruthven is made Prime Minister; Count Iorga, a much-mocked general; Graf Orlok is Governor of the Tower of London; Drs. Moreau and Jekyll are consulted in the Ripper case; Kate Reed, a character cut from the original 1897 Dracula, is a young reporter. Real-life folks feature too: Oscar Wilde stops by; why, even Florence Stoker, Bram’s wife, is part of the action. Too bad Bram himself was exiled after his friends failed to stop the king of the undead. So meta!

Anno Dracula also enlists elements of espionage and detective fiction. The Diogenes Club, a mysterious gentlemen’s group referred to by Doyle in his classic stories, sends for the adventurer Charles Beauregard and requests his services in bringing the Silver Knife to justice. The head of this club? While not mentioned by name, he is the criminal mastermind Fu Manchu. One of Newman’s long-running fictional creations, Geneviève Dieudonné, is a vampire, older than Dracula himself, who is driven and brilliant but an outcast whose long life puts her at odds with the warm, or living, and vampire newborns around her. She and Beauregard, aided by real-life investigator Inspector Frederick Abberline, join together after the infamous murderer, soon to be dubbed Jack the Ripper. Although widowed Beauregard is now engaged to a prim and proper social climber, he will find that he and his beautiful vampire partner are alike in many unexpected ways. Newman’s own characters are rich portraits, compelling and believable, just the kind of people a reader can root for.

Like vampire or Gothic erotica? Well, even if you don’t, you may find yourself quite taken with Newman’s approach to this ever-popular aspect of horror. Dr. Seward, in a bit of Vertigo-esque obsession, “keeps” a vampire prostitute named Mary Jean Kelly, bitten by the doomed Miss Lucy Westenra (you’ll recall, won’t you, that she was Dracula’s first victim, or “get,” in Stoker’s original). And Mary Jean was Lucy’s get, a little girl lost who slaked Lucy’s thirst and was repaid with immortality (undead Lucy stalked children; they called her the “bloofer lady,” remember). Fueled by memories of his unrequited love Lucy, Seward and Kelly engage in bloody erotic fantasies.

Sometimes, Lucy’s advances to Kelly are tender, seductive, mysterious, heated caresses before the Dark Kiss. At others, they are a brutal rape, with needle-teeth shredding flesh and muscle. We illustrate with our bodies Kelly’s stories.

Newman knows his way around the taboos inherent in the vampire mythos.

Other wonderful scenes abound: Beauregard’s misadventures in the city; Jack’s heartless murders; explosive riots in the streets; the hopping Chinese vampire who stalks Geneviève; trickery and ruthlessness, gaslight atmosphere and mystery, general bloodletting and blood-drinking of various sorts. It is definitely part gruesome horror story; Newman regales us with this almost eternal England night. But one thing seems to be missing…

For virtually the entirety of the novel, Count Dracula himself is referred to but never seen; when he finally is revealed, in all his revolting glory, ensconced in a filthy throne room in the Palace, Newman outdoes everything that’s come before. Beauregard and Geneviève have been summoned to appear before him and his Queen, and they are aghast at how they find him in his rank and hellish quarters:

Bestial and bloated, enormous and naked but for a bedraggled black cape… This is no regal steel-haired gentleman clad in elegant black bidding his guests welcome and to leave some of their happiness; this is a bursting tick gorging on humanity itself.

The novel’s ultimate confrontation is at hand.

As a work of alternate history, Anno Dracula is a brilliant success: fact and fiction are bound together with nary a seam to be found. It succeeds as a horror novel because Newman doesn’t stint on the scares. Audacious and unique, written in an unobtrusive manner that doesn’t scream, “Hey, get this name, get that reference, wink-wink,” this is an unparalleled work of popular fiction, filled with inventive touches, expertly twining several sub-genres into an utterly satisfying and engaging novel. My review touches on a only few of many dark pleasures to be found in Anno Dracula; fans of horror, vampire, and 19th century detective fiction will find much to feast upon between these covers (indeed there are a handful of sequels, and the author’s note and acknowledgements are a trove of reference treasures for the vampire/horror completist). Mr. Newman has written an essential, unmissable read that is a nightmare of delight for readers seeking a bloodthirsty new world this Halloween.

Will Errickson covers horror from the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s on his blog Too Much Horror Fiction.