Grady Hendrix, author of Horrorstör, and Will Errickson of Too Much Horror Fiction are digging deep inside the Jack o’Lantern of Literature to discover the best (and worst) horror paperbacks. Are you strong enough to read THE BLOODY BOOKS OF HALLOWEEN???

The preeminent 1970s bestselling horror novel. Millions of copies adorning nightstands and coffee tables everywhere. The unfocused cover photograph of a young girl in torment. The exotic, sibilant title—exorcist—why, the word itself sounded evil. If you were of an impressionable age at the time, surely the iconic imagery of the book alone made a nightmarish impact, even if you didn’t read it. Perhaps even more so, because I’m not even sure The Exorcist (first published in May 1971), the fifth novel from William Peter Blatty (b. 1928, NYC), really is a horror novel.

I know, I know, that old argument: what makes horror fiction, well, horror? The Exorcist has some of the most infamous and eternal moments of shock and terror in popular culture, but is horrifying readers its sole raison d’être? I’d argue non.

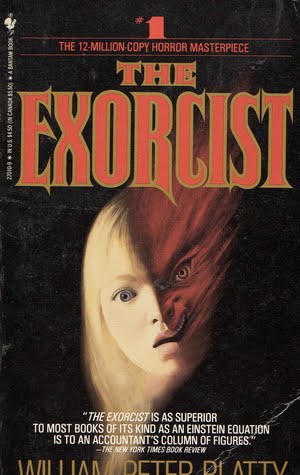

Its vast influence on the horror genre and on publishing in general cannot be overstated. Bookstore shelves started filling up with paperbacks adorned with endless possessed little girls in frilly smocks and Mary Janes, as The Exorcist helped make Satanism and the occult everyday notions. With relish, fans ate up stories of innocent young women defiled, but in the end, saved. But this book bears little relation to literary horror before it.

Somehow I don’t see Blatty tucked up in bed with a worn volume of Poe or Lovecraft or Machen or the like. His forebear really seems to me to be Dostoevsky, or at least Crime and Punishment. Take Lieutenant Kinderman, the movie-loving, world-weary detective (“the world—the entire world—is having a massive nervous breakdown. All. The entire world”). The way he tries to disarm, misdirect, and placate in his questioning to get to the truth reminded me, if I recall correctly, of Petrovich, the detective from Dostoevsky’s classic. And without a doubt, Blatty’s concerns bear similarity to old Fyodor’s lofty theological notions of guilt, forgiveness, love, etc.

But no matter how lofty Blatty’s intentions, he hasn’t written a turgid tract or treatise—no, you just cannot stop reading; this thing moves. At times it’s thoughtful. Other times it’s brooding. Still others, cranked up and hitting on all cylinders, smooth, confident, powerful.

What struck me first was how Blatty tells his story like a journalist. The early scenes with Hollywood actress Chris MacNeil, renting a home in the DC neighborhood Georgetown while she shoots a movie, and her 12-year-old daughter Regan seem like a setup for a nonfiction piece. The slow build is pretty outstanding: the noises in the attic, Regan’s casual mentioning of Captain Howdy or of her bed jumping around, a mysterious book on witchcraft that appears and disappears. The word exorcism isn’t even mentioned till exactly the halfway point. It’s deliciously suspenseful, because what reader today doesn’t know what’s coming? For me that’s part of the fun!

The Exorcist is much better written than I’d expected; compared to other bestsellers of the era, such as Jaws or The Godfather, it’s positively a literary masterpiece. Blatty lays down a bedrock reality with a professional’s writer’s conviction and authority, which sells the outrageous tale; he’s a storyteller who knows that in order to buy the impossible, it must be undeniable. He wisely makes much of the psychological and neurological explanations for Regan’s ghastly and inexplicable behavior, until that becomes untenable. Her fear and confusion is heartbreakingly palpable as she reaches out to Chris, who is terrified that she cannot help her daughter. Denying Regan has become possessed is more ludicrous than thinking she simply has a physiological disorder; now the rational answers from doctors and psychologists are a modern-day mumbo-jumbo: “split personality, psychosomatic, epilepsy, autosuggestion, temporal lobe, neurasthenia, electroencephalograph, clonic contractions…”

Then there’s the famous prologue, with old (and unnamed) Father Merrin on an archaeological dig in Iraq, which seems to imply, upon later reflection, that Regan’s possession is incidental; Merrin and the demon Pazuzu have been on a collision course for who knows how long: “Abruptly he sagged. He knew. It was coming…”

But darkly-natured Father Damien Karras has his own battle: his overarching guilty conscience about being unable, as a priest with a vow of poverty, to provide a comfortable living for his ailing mother. His childhood was grim, hand-to-mouth: “He remembered evictions: humiliations: walking home with a seventh-grade sweetheart and encountering his mother as she hopefully rummaged through a garbage can on the corner.” That’s one of the most vivid descriptions of shame I’ve ever read. Blatty’s depiction of his characters is thorough and sympathetic; he’s able to plumb their depths with fascinating clarity (again, perhaps a Dostoevskian trait).

Ultimately, odd as it may be to say, The Exorcist isn’t about the nature of evil, it’s not about violence and its legacy, and it’s not out to chill us with intimations of our own mortality, as all good horror fiction does—it’s about the corrosive power of guilt and the redemptive qualities of love, wrapped up in an irresistibly glistening package of vomit, bile, filth, foulness, and blood. This is a supernatural thriller filled with a deep and abiding empathy for its flawed, human characters, which is what I think helped make it a massive and unprecedented success. It’s an essential read, but whether all that makes it a horror novel or not is between, well, you and you. And oh yeah, I’ve heard that it was made into a movie too!

Will Errickson covers horror from the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s on his blog Too Much Horror Fiction.