As a writer, you run the risk of discovering a book that is the book—the book you would have written if you had time, money, talent, drive.

When you meet this book you have two choices. You can beat your head against a wall in a rage at the fact that your book has already been written, by someone who is not you, or you can allow than anger to pass through you like fear on Arrakis, bow your head, and humbly accept that this is now your favorite book. Because, by claiming the book as your favorite, you mark yourself as the book’s greatest fan, rather than a failure.

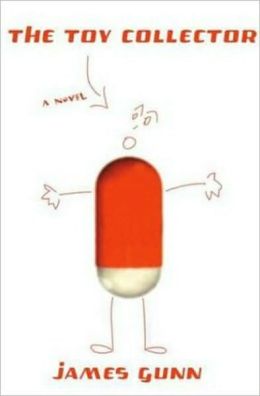

James Gunn’s The Toy Collector is not that book for me, but it comes damn close.

First of all, a note. Why am I reviewing The Toy Collector, a fourteen-year-old cult novel written by a man who chose to pursue film? Because its author, James Gunn, just directed the greatest movie of all time an excellent addition to the Marvel Cinematic Universe called Guardians of the Galaxy. In preparation for the new friggin’ Star Wars this film, I decided to read his book and see how I liked him as a novelist, and how his prose stacked up against his filmmaking. And as much as I like his movies, I was startled to find that this is very nearly the book. I loved it from the first page, and was willing to overlook a few late ’90s/early ’00s writer tricks that would usually annoy me, because the characters were so immediately alive.

On those tricks: the main character’s name is also James Gunn. You’ll just have to accept that. Also, the main character is troubled, addictive, alludes to a DARK PAST, and consistently sabotages everything in his life through the most violent and/or sexual means available, the way most literary protagonists did at that time. Having said all of that, Gunn’s writing is hilarious, right up until the second everything becomes serious, and he allows the emotional undertow to pull characters in without remorse. Just like his films, this book is brutal, and really, really fun. I’ll go ahead and refer to James Gunn the character as James, and James Gunn the author as Gunn, to try to keep this as clear as possible.

The plot is mercifully thin: troubled young man works as a hospital orderly, and begins dealing drugs to pay for his increasingly unmanageable toy collecting habit. Since he believes everyone needs to have a specialty as a collector, he focuses on robots of various types, while his roommate Bill collects TV toys from the 70s, specifically from the “great, never-to-be-matched ABC ’77 Tuesday-night lineup.” James’ toys might give him a connection to his sad childhood, or they might just be feeding a new kind of addiction for him to indulge instead of repairing his relationships with his brother and parents. At a certain point, James embarks on a series of picaresque sexual adventures, but the real meat of the book (for me at least) was in the family stuff.

The present-day story is intercut with flashbacks to James’ childhood, primarily the epic adventures he had with his brother, Tar, and their best friends, Gary Bauer and Nancy Zoomis. These adventures were enacted by an array of plastic heroes: Scrunch ‘Em, Grow ‘Em Dinosaurs (otherwise known as The Greatest Toy in the World); Chubs, a Fischer-Price figure of unstoppable strength; Ellen, who wielded a magical movie camera; Larry the Astronaut; and, best of all, Dan Occansion, professional daredevil, who was game for everything whether it be a flight on a 4th of July rocket or a ride on the back of an unwilling duck.

In the present-day, James’ collection has combined with Bill’s to take over the entire apartment:

The top four shelves held Bill’s TV toys: the Tuesday-night folks, Romper Room, and Welcome Back, Kotter, Charlie’s Angels and What’s Happening?, a Mr. Ed doll, and perhaps the largest collection of Little House on the Prairie toys in the world. My four shelves were almost all robots: Captain Future Superhero, Changing Prince, Deep Sea Robot, Dux Astroman, Interplanetary Spaceman, Chief Smokey, Electric Robot, Winky, Zoomer, Mr. Hustler, New Astronaut Robot Brown, C3PO, Rotate-O-Matic, Space Commando, Astro Boy, Robby, Maximillian,and others. More gewgaws and trinkets lay on the other horizontal surfaces in the room.

“I didn’t believe there would be so many,” Amy whispered.

My brother’s eyes flooded with awe, and that was a sign of the power of our collection.

The book reads as though Gunn initially intended it to be a Denis Johnson-style meditation on darkness and loneliness, but as you read it becomes a much fuller story. This is all down to the toys, and James’ love/hate relationship with Tar. In the flashbacks the Gunn brothers are suburban desperadoes, fighting bullies, defending each other from their parents, and supporting their friends no matter how crazy shit gets. In the present, however, James and Tar barely speak. Tar is successful, with a girlfriend, a job, AA meetings, and a layer of selective memory spackle applied to the worst aspects of his parents. James can’t forget the past, and he regards his brother as a traitor for his ability to do so.

Gunn pulls a masterful trick in erasing the ironic distance that an adult reader would have watching kids play with Fischer-Price figures. We are told which kid controls which toy, and then we’re dropped into the toys world as they fight evil, protect each other, and occasionally, die. These deaths are real to the kids, and Gunn commits to giving them emotional weight, rather than just letting them foreshadow the darkness that awaits the children in adulthood.

It would be easy to assume that the toys offer James a way back to his lost innocence, except that the more Gunn shows us of James’ childhood, the more we realize that there isn’t an innocence there for him to recapture. James and Tar don’t have a happy home life, and while you could argue that they create an alternative family with their friends, it soon proves to be just as unhealthy. James is, instead, searching for a pure sense of meaning and acceptance. The toys could allow the kids to enact revenge fantasies, or scenarios where they escape their families and live better lives. Instead, they choose to stage battles of good and evil. They flood their games with “Satanists” and then sit back helplessly as nobility and friendship are overpowered by the superior forces of darkness. Within the game, after all, they are their characters, and interfering to make things go the way they want would be to break the veneer of fantasy and ruin the game. At least, that’s what they think until one of them goes ahead and reaches into the game as himself. This moment becomes the crux of the book, and the heart of James’ endless anger and searching.

The idea of the eternal man-child, surrounding himself with toys to recapture innocence – why do we coming back to this? The Dissolve did a piece on 40 Year Old Virgin last week that spoke about the ways that Steve Carrell’s character, Andy, became so trapped in the ephemera of his youth that he couldn’t move on and engage in a sexual relationship until he got rid of his toys. It was this trope that many of the initial reviews of The Toy Collector mentioned. However, I don’t think the book supports this reading. The toys aren’t driving James’ girlfriends away, his terrible behavior is. The toys frighten Tar only because he’s worried that his brother’s found a new (and expensive) addiction.

But much like the rest of Gunn’s oeuvre, he’s using an established form to make a larger point. Slither is a schlocky horror film that is actually a meditation on the bonds and commitments of marriage. Super is a superhero movie that’s really about the line between religious faith and madness. And Guardians of the Galaxy is a space opera that cares more about character development and friendship than aerial acrobatics. The Toy Collector isn’t really about the toys, or the antiques dealer who sells them to James and Bill, or about James’ need to grow up and put away childish things. It’s about a person who veers from obsession to obsession on an impossible search for meaning and beauty. By taking us so deeply into the games James and his friends play, I think Gunn is making a different argument entirely: why do we need to put away childish things? Maybe humans needed to when life was more dire. Maybe we’ll need to do it again, in the post-climate-collapse Road Warrior future that awaits us. But right now humanity is in a bubble where we can keep our toys, treasure our imaginations, and try to bring our meaning into life, the same way we brought it to games when we were kids.

The Toy Collector is published by Bloomsbury.

Leah Schnelbach is proud of her toy collection. If that makes her a man-child, so be it. Sometimes she tweets!