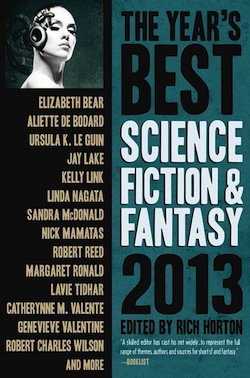

The 2013 edition of Rich Horton’s The Year’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy, published by Prime Books, has recently been released—collecting, as it says on the tin, the best of last year’s short-form SFF. Featuring thirty-three stories by a variety of writers, from Ursula K. Le Guin to Xia Jia (translated by Ken Liu) and then some, this year’s edition has a particularly pleasing spread of contributors. Some of those are familiar; some are more new.

Of the various year’s best anthologies, the Horton series is a favorite of mine. I have reviewed past editions (such as 2011’s), and this year shares a similar tone and spread of stories with previous installments. Horton tends to include a diverse range of authors with pieces from various publications; also, because the series is more generally dedicated to speculative fiction as a whole, it tends to represent a more accurate range of the year’s greatest stories than those best-ofs that focus only on one genre or another.

Due to the volume of stories collected here, I’ll focus on a few of the most notable and the least successful to give an idea of the range—and, for integrity’s sake, I’ll be skipping over stories originally published by Strange Horizons (what with my editorial position and all). Of note: this volume contains two stories by Aliette de Bodard—a rare occurrence in a year’s best!—and also a novella by Jay Lake, the only longer story in the book.

There were quite a lot of science fiction stories in this year’s collection, and many were strong showings. In this vein, I was particularly fond of “In The House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns” by Elizabeth Bear, “Prayer” by Robert Reed, and “Two Houses” by Kelly Link. These stories are all remarkably different from each other. The Bear is a near-future mystery set in a sustainably developed city; the Reed is a short, provocative piece about a near enough future that has gone somewhat awry and a young girl’s place in it; and the Link is an atmospheric, eerie ghost-story set during long-term space travel. They’re all science fiction, certainly—but together, they represent the variety available to the genre. It goes without saying, perhaps, that the prose in these stories is strong, the settings evocative, and the conflicts gripping.

Another theme that reoccurs throughout the book is that of the reflective, affect-oriented piece—thought-provoking and atmospheric, not necessarily guided by a conventional plot or resolution. While this is not always the best choice, some of these stories are intense and linger with the reader: “A Hundred Ghosts Parade Tonight” by Xia Jia, “Heaven Under Earth” by Aliette de Bodard, and “Elementals” by Ursula K. Le Guin. Xia Jia’s story is the closest to a story with a conventional plot—the slow reveal of the fact that the world, and the protagonist, aren’t what they seem—but the ending is breath-taking and upsetting. The world is rendered in only the broadest strokes, leaving enough to the imagination that the main focus of the piece remains the boy’s emotional connections to his adoptive family of “ghosts.” Aliette de Bodard’s piece, however, is a complex story of bureaucratic marriage and procreation, gender, and identity—it’s idea-driven, and long after reading it, I continued to think about what the story was saying and doing with its themes. It’s not a comfortable piece—the treatment of gender, roles, and identity treads on complicated and potentially dangerous territory—but that makes it delightfully interesting. Finally, the most “broad strokes” of all of the stories is the Le Guin: it’s just a series of shorts about imaginary creatures, but these creatures represent changing cultural mores and ideas.

There were, of course, less strong stories in the course of the book. Some of these were pieces set in existing universes that didn’t stand well on their own; others were problematic. “Under the Eaves” by Lavie Tidhar, set in his Central Station world, was unfortunately not the strongest piece I’ve seen from him recently—it is perfectly fine, as a story, but in the end is fairly shallow. Similarly, “The Weight of History, The Lightness of the Future” by Jay Lake is set in an existing universe—and it reads far longer than it actually is to a reader who is not particularly immersed in that universe. As it’s the only novella in the book, this is a distinct problem. It also ends on an extremely open note, assuming once again that the reader is invested in the world already and will follow up to see what comes next.

Otherwise, some stories I found simply unpleasant. “One Day in Time City” by David Ira Cleary relies on a dialect-inflected prose that becomes grating rather quickly; it also treats its primary female character through a problematic lens, relying on some of my least favorite sleazy-romance tropes. “Sunshine” by Nina Allan was by far my least favorite, though—it’s Yet Another Vampire Story trying to make vampires less sexy and more animal, but it ends up being at once dull and gratuitous. There’s nothing fresh in the slow-moving, obvious narrative to make reading a great deal of rape and the protagonist fantasizing about rape palatable. Rather than commenting on the genre or doing something new and interesting, this piece rehashes too many prior stories.

Generally speaking, this is perhaps not the strongest edition of The Year’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy. Though I’m all for a big book with a great deal of variety, I also found the over five hundred and fifty pages of short fiction here a bit difficult to power through; occasionally, I found myself losing interest. One issue is that many of these stories, though technically interesting or in possession of a cool idea, are scant in terms of lingering effect—pretty but lacking in substance, in short, as pointed out in a few cases above. They’re good, but they’re not the best.

Additionally, the organization of stories in the table of contents does not necessarily guide the reader through seamlessly. There are several occasions at which a disjunction in tone or content between one story and the next provided a stopping point—whether or not I was quite intending to stop reading yet. I will say that this criticism assumes a desire to read the anthology all at once. If you plan on spreading it out, a story here and there, the organization and the potential for disjunction becomes less of an issue—but, this is an anthology, a whole intended to be coherent, so I would have preferred a smoother reading experience. Another common problem with books published by Prime crops up here, too: an unfortunate number of typos and small errors that a cautious proofreader would likely have caught. This is something I’ve noted regularly in their publications, particularly the Year’s Best series. It’s a minor inconvenience, but one I would like to see improved in the future.

But overall, The Year’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy 2013 offers a pleasant spread of stories published across the genre world in 2012 and a unique perspective on the variety of the field. For that reason, it’s a worthwhile read. Horton’s selections are, for the most part, engaging, and even when they’re not to my tastes, they do tend to represent one generic niche or another. I enjoyed the experience of re-reading notable stories from last year I’d already seen, as well as finding a few new gems that I missed in their initial publication—and that’s my favorite part of best-of collections, generally.

The Year’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy 2013 is available now from Prime Books.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.